I know why people turn to conspiracy theories in uncertain times. I did the same when my husband had a brain tumor.

It was October 2005 when my husband Mike called me with the news. I was working on my dissertation in my home office, and he had just received the call from his ophthalmologist.

“I have a brain tumor. It’s called a craniopharyngioma. It’s a benign tumor near the pituitary gland.”

“Benign” is a misnomer for the tumor in his midbrain that would ultimately rob my smart, improv comedian, graphic designer husband of not only his vision but his short-term memory and his ability to care for himself over the following nine months.

In the early days of the diagnosis, I was debilitated by grief and anxiety. One night, I wept at dinner. “It’s not fair,” I remember repeating.

He calmly responded, “Who would it be fair for, though? Would it be fair if I were old? Would it be fair if we did not have a baby? It has nothing to do with what is fair, Danna. It is just random.”

It is just random. These words were not comforting to me. They made me angry.

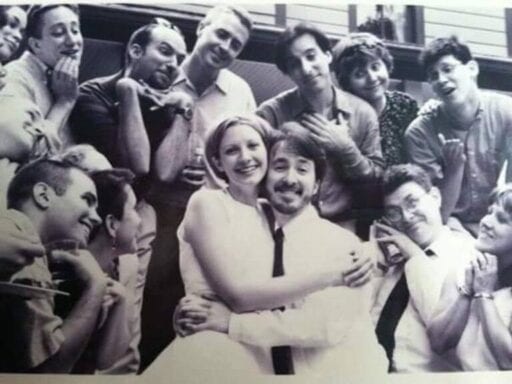

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19974590/mike_danna_bax_2005.jpg) Courtesy of Dannagal G. Young

Courtesy of Dannagal G. YoungMike lived with, in the language of social science, seemingly infinite tolerance for ambiguity. He loved to take adventures and felt little need to know what was going to happen next. But I was not like Mike. I had (and have) a high need for closure. I dislike uncertainty and need control over my world. So, while Mike was satisfied with the notion that his brain tumor was “just random,” I was not.

I started searching for information to account for the causes of his brain tumor, which eventually led me down a dark internet rabbit hole. Perhaps there were chemicals at his job that caused the tumor, I thought. One of his 30-year-old coworkers had died of cancer several years prior. That seemed weird, didn’t it? And now Mike with this brain tumor? When I mentioned this to his doctors, they pointed out that for a company of more than 300 employees, these numbers were far below average.

What about environmental carcinogens, then? I thought. We had recently moved to a new neighborhood near the site of an old diaper company that was in need of environmental remediation for spilled “chlorinated solvents and heating oil” from the 1970s and ’80s. That seemed bad and probably had adverse effects, I thought. But Mike had started showing symptoms of the tumor just three weeks after we moved in, and the doctors explained that craniopharyngiomas don’t appear that fast. It had likely been present in Mike’s brain for years, maybe decades.

Each time I landed on a possible culprit, my anger reenergized me. Instead of making me feel hopeless, it gave me a target and suggested there might be some action I could take. If it were from his work or from an old factory site, maybe I could file a lawsuit. Maybe I could launch an investigation or trigger some media exposé. If I could just find the right person or thing to blame, I could get some justice. Or vengeance. Or … maybe just a sense of control.

Ambiguity, anger, and the elixir of “assigning blame”

In 2001, social psychologists Jennifer Lerner and Dacher Keltner studied how anger and fear have very different effects on how we think about ourselves and our world. Their research found that feelings of anger (compared to fear) are associated with increased feelings of certainty, control, and optimism. Especially when people contemplate “ambiguous events” — such as having a heart attack at a young age or being unable to find a job — anger translates into higher perceptions of control. Once anger triggers feelings of control, feelings of optimism follow.

This is why identifying someone to blame for Mike’s tumor gave me the focus and will to stop crying and get out of bed. Instead of wallowing in grief, I became a warrior furiously charging in a precise direction. My anger invigorated me; it lifted me up out of the sea of muck we were stuck in.

Under conditions of uncertainty, information that helps direct our negative emotions toward a target is psychologically comforting. When we feel powerless in a situation that is both complex and overwhelming, the identification of people and institutions to “blame” feels good to us.

This explains not only families lashing out when their loved ones are ill, but also the appeal of conspiracy theories more broadly. Especially in the context of ambiguous and terrible events like 9/11 or the Sandy Hook shooting, conspiracy theories increase perceptions of control. Such narratives typically point to the existence of secret plots by powerful actors working behind the scenes, either to cause the horrible chaos or to fabricate it. The anger we then feel toward these “powerful actors” is accompanied by a feeling of efficacy (confidence in one’s ability to effectively navigate the world), hence increasing the likelihood that we will take action — by engaging in political participation, protest, or, in the case of a loved one’s medical situation, maybe filing a lawsuit.

I know what it’s like to want to do something tangible in the face of lack of control. As weeks turned to months, and three surgical procedures turned to 12, well-meaning friends asked about potential malpractice — maybe the powerful doctors behind the scenes had some secret plot to deliver substandard care. But each time I started down that path, even in my own mind, it quickly fell apart. Who had acted with negligence? No one. Had Mike received the proper standard of care? Above and beyond. Were his complications related to the care he was given, or to the tumor itself? None of his complications were from his care. Every complication had been the fault of what we came to call the S.F.T. (the “stupid f***ing tumor”).

Most importantly for me: Assigning blame and looking for retribution was antithetical to Mike’s governing philosophy, which was to accept life as it comes and be open to what happens.

Embracing uncertainty rather than trying to control it

Having lived with uncertainty, powerlessness, and negativity during Mike’s illness, life during Covid-19 feels eerily familiar from an emotional standpoint. Today, many of us feel little efficacy or agency over the course of this virus, its impact, or its spread. We don’t know when or how the situation will resolve. And we’ve got a nagging sense that life will be forever altered, perhaps in negative ways.

These feelings of collective uncertainty, powerlessness, and negativity likely account for the popularity of Covid-related conspiracy theories circulating online. Perhaps you’ve seen folks on social media claiming that Bill Gates is responsible for the coronavirus (he is not), or that 5G towers are somehow amplifying the virus (they are not), or maybe your friends or family have shared pieces of the propagandistic “Plandemic” documentary in which discredited biologist Dr. Judy Mikovits advances several false claims — including the notion that wearing a mask “literally activates your own virus” (it does not).

Searching for “new answers” to assign blame and impose order on this life-altering pandemic through conspiracy theories and allegations of secret plots may feel comforting — even invigorating — in the short term. But such actions will not help solve this crisis, and they certainly won’t bring us peace.

Just as I had been desperate to feel control over the chaos of Mike’s illness by wanting to assign blame, today many of us are desperate to feel control over the pandemic. But while it may have been temporarily empowering to identify people and things to blame for Mike’s tumor, it quickly became clear that these behaviors would not cure Mike. And they certainly didn’t bring me peace.

Interestingly, there were some behaviors that did bring me a feeling of control and peace during the months that Mike was hospitalized. I stopped searching the internet and started just being present with Mike, focusing on my gratitude for friends and family, making sure Mike was comfortable and surrounded by friends. I created a Google calendar where people could sign up to help him at mealtime and visit when I had to be home taking care of our baby. I organized for people to bring the nurses doughnuts and treats, and made sure Mike was comfortable with cozy blankets and calm music playing.

Today, when I look at social media, sure, I see a few people sharing Covid-19 conspiracy theories, but what I see more of is people creating feelings of control and peace in more functional ways: sewing masks, helping neighbors get food, scheduling Zoom happy hours, gardening, and expressing gratitude for health care workers. These actions signal a healthier approach to chaos and trauma — not one anchored in either anger or fear but rooted in presence and gratitude, and echoing a profound tolerance for ambiguity.

It’s okay to not know

On July 18, 2006, Mike died surrounded by a sea of friends. His doctor wept and hugged me. “I really thought we could get to the other side of this one,” he told me. Then he placed a hand on my arm. “I know it’s a terrible time to ask this, Danna. But do you want to do an autopsy?”

I thought of the months of grueling procedures, doctor’s appointments, and hospital stays. Then I thought of my happy and hilarious best friend, Mike Young, and his infinite tolerance for ambiguity. Channeling Mike, I wiped my face, then raised an eyebrow, “Autopsy? Why?” I whispered dramatically, feigning surprise. “Do you think he was murdered, Doctor?”

He paused — then we both laughed a bit, hugged, and wept some more.

Mike was right. It was just random.

Dannagal G. Young is an associate professor of communication and political science at the University of Delaware. She has authored more than 40 academic articles and book chapters exploring themes related to political entertainment, media psychology, public opinion, and misinformation.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Dannagal G. Young

Read More