Hurricane season starts in June.

Without proper planning, the threat of hurricanes combined with Covid-19 is a recipe for disaster.

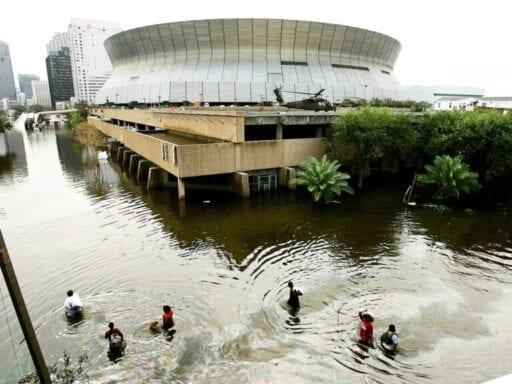

Think about how, when Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans in 2005, around 20,000 people took refuge in the Superdome stadium. By their very nature, hurricanes force people to gather close together in shelters, at treatment locations, and during evacuations — at much higher numbers and densities than the CDC recommends for countering a Covid-19 outbreak. And vulnerable populations such as residents of senior care facilities and individuals with disabilities are particularly affected by both hurricanes and infectious diseases.

The Atlantic hurricane season starts on June 1, and every state and territory on the Atlantic coast is vulnerable. This year’s hurricane season is predicted to be more active than normal, with a higher likelihood of a major hurricane touching down on the US coastline. Given indications that the Covid-19 outbreak will continue into the hurricane season, this situation requires a new kind of planning from both emergency managers and the public. And that planning needs to happen now.

Emergency managers — including federal officials, private sector authorities, and nonprofits — need to analyze their strategies to develop hurricane-plus-Covid-19 scenarios. This approach can yield complementary strategies instead of two separate plans for each situation.

Among the many issues to be considered:

Response systems may already be at capacity or overwhelmed

Covid-19 is already placing unprecedented strain on disaster management, health, and other systems; a hurricane will exacerbate that strain. With outbreaks across the entire nation, an area hit by a hurricane is less likely to get aid from other states or regions. Federal resources are limited in authority and capacity. Many hospitals are struggling to provide care due to limited resources and personnel, and at the community level, many are experiencing the economic effects of Covid-19 and have fewer resources and greater uncertainty.

Instead of assuming “business as usual,” plans need to be reassessed. For example, this might entail looking at how workforce shortages, delays in material and money, and insufficient hospital capacity impact hurricane response, and incorporating those changes into plans.

Evacuation and sheltering will have extra complications

Traditional calculations of when to issue evacuation warnings should be reassessed in light of Covid-19, which may change decisions of when to fortify and shelter in place.

Emergency evacuations are typically called for based on the expected impact of the hurricane, and may involve large populations moving to concentrated locations like emergency shelters or hotels — or leaving the area entirely. Even without a disease outbreak, evacuation decisions are always difficult, both practically and politically. The decision process should be altered during an epidemic because usual evacuation risks (traffic accidents, for example) will have to be balanced against the risk of increasing disease transmission, which could have longer-term effects than the hurricane itself.

The pandemic makes clearly communicating exactly who should evacuate even more important: Those in the storm surge zone should go while others should be encouraged to shelter in place and be prepared for wind, rain, and power outages.

If evacuation occurs, emergency managers may need to get creative. Evacuees should be screened for symptoms of the coronavirus, and those with symptoms should be placed in separate facilities. The elderly and immunocompromised should be separated as much as possible and housed in smaller facilities to reduce their risk of catching the virus. Hotels might be used to keep people apart, though large shelters and evacuation camps crowded with people may be inevitable. There’s a much higher possibility that supplemental facilities, such as military shelters and hospitals, may be needed.

Stocking up on supplies and food

Household stocking of supplies may be even more critical than normal to get through the hurricane season. People have been stockpiling food and supplies (sometimes to the extreme) in response to Covid-19. Some of these stocks can be doubly useful for hurricanes. However, the coronavirus outbreak has also led to unique needs, such as disinfectants, soap, and masks. People should remember these different needs as part of their hurricane planning.

Response organizations might also be able to combine their supply planning for Covid-19 and hurricanes. Some of the materials are distinct, of course: Hurricane preparation requires material to harden buildings and careful transportation route protection, while Covid-19 preparation requires personal protective equipment and other medical supplies. However, their needs are similar in many other respects, requiring stockpiles of emergency food and supplies and dedicated response staff.

Stocking up on supplies is also an equity issue. Poorer and more vulnerable populations might have greater needs and fewer resources to meet those needs. Response organizations should look to support these groups as part of preparedness planning.

Deploying emergency workers

Hurricane response involves a great number of people, including first responders like police, firefighters, search and rescue organizations, utility companies responsible for getting critical infrastructure back up and running, and incident managers who coordinate response efforts.

Since people themselves spread Covid-19, how do you safely deploy them across the country, as well as deal with reductions in staff availability?

Strategies are already being developed for managing the coronavirus outbreak in a way that minimizes disease spread, such as remote emergency operations centers and enhanced personal protective equipment for first responders. Such strategies will need to be considered when dealing with the hurricane workforce.

Economic recovery

Disaster recovery is a long-term process that plays out over the course of months, years, and decades. This means that much of the recovery efforts should be occurring after we might expect to have a coronavirus vaccine. However, the economic slowdown from the pandemic may affect the speed and scale of recovery.

Emergency managers generally view individual households as the center of recovery efforts. Amassing an emergency fund is a crucial part of hurricane preparedness, but for the nearly half of Americans living paycheck to paycheck, that’s almost impossible. With millions more people out of work entirely since March, many more people are likely to need external aid, such as financial support to secure temporary housing and to repair damages to their homes.

Instead of assuming people are able to recover on their own, the government may need to play an even more active role in assisting with the recovery.

Aaron Clark-Ginsberg is an associate social scientist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation. His research focuses on disaster risk management, including issues related to disaster risk reduction, response, and recovery.

Gary Cecchine is director of the RAND Gulf States Policy Institute and a senior policy researcher at the RAND Corporation. His research focuses on emergency preparedness and response, environmental and health policy, and military medicine.

W. Craig Fugate is one of the world’s leading experts in emergency and crisis management. The head of the Federal Emergency Management Agency under President Obama, Mr. Fugate is currently Chief Emergency Management Officer for One Concern, an AI company focused on using big data to improve disaster management.

Craig Bond is a senior economist at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation. His research focuses on applied welfare economics, including risk and resilience issues affecting the Gulf Coast.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Aaron Clark-Ginsberg, Gary Cecchine, Craig Fugate, and Craig Bond

Read More