Trump ran on immigration in 2016. His focus has shifted to maintaining “law and order.”

When Donald Trump descended a golden escalator at Trump Tower in New York in 2015 and declared that Mexican immigrants were “bringing drugs, they’re bringing crime, they’re rapists,” he not only announced he was running for president — he set the tone for a campaign where immigration took center stage.

Four years later, Trump has fundamentally reshaped the immigration system in ways that would be difficult, if not impossible, to reverse. In a second term, he could embrace further restrictionist policies.

But he hasn’t taken a victory lap. Instead, on the campaign trail, the topic has largely receded into the background. The rhetoric Trump used against immigrants in 2016 — painting them as a foreign danger to American life — has been, in 2020, more often turned against protesters, particularly those affiliated with the Black Lives Matter movement.

Trump has presented himself as the “law and order” candidate. He was a vocal opponent of the protests over racial inequity and police violence that broke out over the summer and efforts to defund the police. And he has stoked fear about public safety in Democratic cities and surrounding suburbs, including exaggerating the looting and violence that broke out amid some otherwise peaceful protests.

Immigration hasn’t been fully absent from the campaign. Trump still repeats anti-immigrant rhetoric at his rallies and has spent millions on amplifying that messaging through ads. At a rally in North Carolina on Sunday, he read aloud the song lyrics of “The Snake,” which tells the story of a “tenderhearted woman” who unsuspectingly rescues a half-frozen snake that later bites her. Trump has invoked the song, once a regular feature of his rallies in 2016, as a xenophobic parable about the risks of unauthorized immigration.

Meanwhile, Trump administration officials — including those at the Department of Homeland Security and White House senior adviser Stephen Miller — have pursued a parallel strategy of stoking fear about the dangers of Democratic immigration policies in critical swing states.

But while the stakes for immigration are high, the issue hasn’t been central to Trump’s pitch. “In 2016, immigration was seen by Republicans and Trump as an issue that not only mobilized white grievance voters that form his core support, but also peeled off swing voters in places like Michigan, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania,” Frank Sharry, the executive director of the immigrant advocacy group America’s Voice, said. “It was a double hit.”

Trump has once again sought to make people of color the enemy as a means of scaring white voters into supporting him, but this time the targets are different, Sharry said.

“It’s still racism,” he said. “But it’s not the xenophobia branch of racism.”

Immigration helped Trump win in 2016. But the playbook failed in 2018.

When Trump announced his run in 2016, he also vowed to build a “great, great wall on our southern border” and that he would make Mexico pay for it.

“Build the wall” became a rallying cry among his supporters, who embraced his claims that the US immigration system served the elite, not America’s blue-collar workers, as well as his inaccurate)= portrait of immigrants as violent criminals and low-skilled workers who steal American jobs and drain taxpayer resources.

But the issue extended beyond his hardcore supporters. In 2016, immigration was a top motivating issue for voters: 70 percent said immigration was “very important,” more so than Supreme Court appointments, race relations, the environment, and abortion. Trump and his party had successfully put the issue on the national agenda.

Immigration also featured prominently in analyses of why Trump won and in voters’ rationale for their choices. His win was largely attributed to a revolt among white working-class voters who overwhelmingly cited anxiety over immigration as the reason they voted for Trump. Views of immigration also represented one of the biggest divides among people who voted for Trump and those who voted for Hillary Clinton.

The strategy, though, had limits, which became evident during the midterms in 2018, when Trump stoked fear about an “invasion” of migrant caravans and foreign “criminals” and “smugglers” while stumping for Republican candidates. The Republican pollster David Winston later concluded that the party’s focus on immigration, rather than the then-strong economy, is what ultimately cost Republicans the House majority that year, eroding their support among independents. Democrats, who largely focused on health care instead, took back 41 House seats.

Trump has largely delivered on his promises to restrict immigration overall. But the policies that have come to define Trump’s record on immigration — including the separation of migrant families on the southern border and his attempt to end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, which has allowed more than 700,000 young unauthorized immigrants to live and work in the US — are deeply unpopular among voters of both parties.

It also seems that voters’ attitudes toward immigration are changing, possibly an effect of the restrictionist policies Trump has pursued. More Americans now welcome increased levels of immigration. And immigration has declined in importance to voters overall since 2016, eclipsed by more pressing concerns including the pandemic.

“The bottom line is basically that immigration as a wedge issue has lost its edge because instead of working among swing voters, it backfires among swing voters,” Sharry said. “And it’s gone from being an issue that Democrats feared to being the issue that Republicans avoid.”

Immigration is still firing up Trump’s base — but that might not be enough

But for Trump’s base, immigration remains a top motivating issue — and the president still aims to satisfy them with plenty of anti-immigrant rhetoric on the campaign trail.

His primary defense to criticism of his response to the Covid-19 pandemic is that he decided to impose a travel ban on China. In the final presidential debate — the only one that addressed immigration — he falsely claimed that only immigrants who have an “extremely low IQ” show up for court hearings and that migrant children who had been separated from their parents by his administration had been smuggled across the border by criminals and gang members.

He has also spent millions on campaign ads touting his immigration policies across swing states, including Pennsylvania and Michigan, in the final weeks of the campaign. That includes a $7 million Facebook ad buy, including some ads that were later pulled by the company (though not before they reached hundreds of thousands of people) because they claimed, without evidence, that admitting refugees to the US would increase Americans’ risk of contracting the coronavirus. Immigration was also the subject of his second-biggest TV ad buy from September 1 to October 15, according to the New York Times.

One ad, which ran in Florida, Arizona, North Carolina, Georgia, and Wisconsin, decries Biden’s plan to legalize millions of unauthorized immigrants living in the US, claiming it would allow them to compete for American jobs and become eligible for public benefits.

Miller, Trump’s senior adviser and the architect of his immigration policy, has also acted as the president’s surrogate, speaking in hyperbolic terms about what he sees as the “nightmare of epic proportions” of Democrats’ immigration policies in an October 29 press call. He stoked fear about what would happen if Biden were to begin releasing certain immigrants who cross the border without authorization into the interior of the US, as he has proposed.

“Within a week of that happening, there would be a rush on the border on a global scale unseen before in the whole of human history,” he said. “Every smuggling and trafficking organization on planet Earth would get the news and millions will come, not just from this hemisphere, but from the whole of the planet.”

These eleventh-hour appeals on immigration smell of desperation as Trump’s path to victory appears increasingly narrow.

“It’s clear that Trump isn’t loosening his grip on immigration, but rather desperately grasping at straws to reach a bloc of voters who oppose his record on the issue and reject his vision of America,” Tyler Moran, the executive director of Immigration Hub, said in a statement.

Immigration enforcement agencies have been on a publicity blitz

In the last stretch of the campaign, Trump administration officials attempted to put immigration back on the map as an election issue.

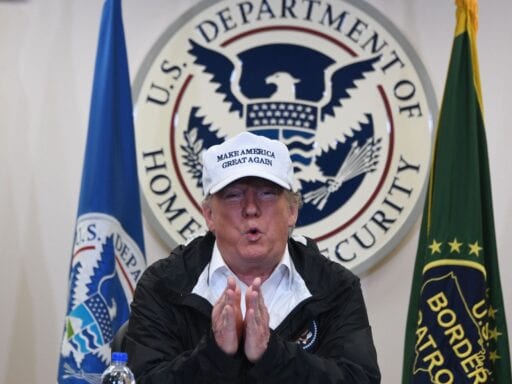

Officials at the Department of Homeland Security, including acting Secretary Chad Wolf and his deputy Ken Cuccinelli, have been on a tour of several battleground states — Pennsylvania, Arizona, Minnesota, and Texas — holding at least five press conferences in the past six weeks amplifying the president’s messaging on immigration.

Wolf and Cuccinelli have been among the president’s staunchest defenders in the administration, going to bat for him in the media over the years, but these press conferences stand out because they are so close to Election Day.

Some of the press conferences have concerned routine enforcement actions that would typically be publicized with a simple press release. For instance, Cuccinelli traveled to Pittsburgh on October 21 to speak about the arrest of 15 foreign students accused of visa fraud, only a fraction of whom were actually arrested in Pennsylvania (the agency didn’t specify how many, but acknowledged that at least some of the arrests had occurred in Massachusetts, Washington, DC, Texas, Florida, New Jersey, and Tennessee.)

“Today’s announcement is just another example of the Trump administration not only putting America first but making sure the laws of our immigration system are enforced,” he told reporters at the time.

Also in Pennsylvania, the federal government has erected billboards warning of immigrants “WANTED BY ICE” who had been charged with or convicted of crimes ranging from assault to robbery. Because they had been released from jail on bond or after completing their sentences without being referred to ICE, the agency claims on the billboard that such sanctuary policies are a “REAL DANGER.”

The border wall has also become a prop in the agency’s public messaging. After racing to finish the border wall in the months leading up to the election, DHS officials have been eager to claim that Trump made good on his campaign vow. (Almost 400 of the 450 miles of border wall Trump promised by the end of the year have been completed, but Mexico never paid for it — rather, that $15 billion burden fell on taxpayers and largely was transferred from the Pentagon’s budget.)

Wolf traveled to the border on October 29 to tout the progress on construction, making abundantly clear what he thought was at stake in the presidential election. He said that Biden’s policies would create a surge of migration at the border and pose a threat to national security.

“Let me be clear, each of those policies would endanger the lives of the border patrol and Americans across the country,” he said.

He also tweeted out a video making jabs at journalists who cast doubt about whether Trump would complete the border wall and whether it would even serve its intended purpose of “securing the border.” It’s not clear whether the video was produced by the Department of Homeland Security, but it might as well have been a campaign ad:

They said it couldn’t be done…

They tried to block it

They tried to spin it

They tried to hide the truthThey were wrong. 400 times and counting. pic.twitter.com/MWWP4cgoPi

— Acting Secretary Chad Wolf (@DHS_Wolf) October 29, 2020

David Lapan, a former spokesperson for DHS, called it a “misuse of [government] resources” and “clear electioneering.”

Trump has made “law and order” the foundation of his campaign instead

Trump’s messaging on immigration has become part and parcel of his broader theme of “law and order,” a phrase repeated by politicians since Barry Goldwater used it as a cudgel against the civil rights movement and that Trump and Vice President Mike Pence have uttered more than 90 times on the campaign trail this year. While the focus of Trump’s ire is different than that of his anti-immigrant tirades in 2016, it’s motivated by the same goal: to maintain a white, European-majority population and cast people of color as the enemy.

“Trump’s reelection campaign has implemented a bifurcated strategy to serve up xenophobia to his base and target suburban voters with ‘law and order’ dog whistles against immigrants and communities of color,” Moran said.

In 2016, he stoked fear about international criminal gangs like MS-13 and “invasions” of migrant caravans. Now he’s stoking fear about looting in liberal cities and an “invasion” of low-income housing into suburbia.

Upon taking office, he said that he supported immigrants who sought to come to the US legally, but denounced Democratic “sanctuary cities” that refuse to cooperate with federal immigration authorities as “lawless.” (Though he later slashed legal immigration, too.) He also described the southern border as “lawless,” implementing a “zero tolerance” policy that aimed to prosecute anyone who crossed the border without authorization. Now he’s demonizing Democratic cities that allow “lawless” protests to continue.

The parallels in his language are no accident. They have the effect of tapping into fear of the “other” among white voters — whether that’s immigrants or the people of color leading the summer’s protests. It resonates with some voters: One Republican in Minnesota told the New York Times in 2018 that she feared migrant gangs could seize summer lake homes in the state.

“What’s to stop them?” she said. “We have a lot of people who live on lakes in the summer and winter someplace else. When they come back in the spring, their house would be occupied.”

It’s for that reason that Trump has made his candidacy synonymous with white power, an association he has repeatedly shown reluctance to disavow. When asked to condemn white supremacists at one of the presidential debates, he instead told them to “stand back and stand by.” Some of his supporters have made their support for white supremacy plain, including one attendee at a recent rally in Florida who flashed a white power sign.

But in a country that is on track to become a majority-minority country by the 2040s, it’s unclear how Republicans, if they continue to embrace the nativism and racism stoked by Trump, will still win elections.

Author: Nicole Narea

Read More