It works just like impeaching a president.

Whether or not the Senate approves Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court nomination, a big question looms: Should he be impeached?

Kavanaugh, who is a judge on the Court of Appeals for the DC Circuit, now faces three named accusations of sexual assault and misconduct, all of which he has denied. But even before the allegations, former deputy assistant attorney general Lisa Graves called for Kavanaugh’s impeachment about an entirely different thing — she accused him of lying about stolen memos the Bush White House and congressional allies used in early 2000s judicial confirmation fights under oath.

It’s unlikely a Republican-controlled House would act on such an impeachment, but if Democrats took control, they could pursue charges related to both sexual wrongdoing and lying about the memos, whatever happens to Kavanaugh.

Kavanaugh is not the only jurist facing such calls. Jill Abramson, the former executive editor of the New York Times, in February called an impeachment inquiry against Justice Clarence Thomas for lying about his sexual harassment of Anita Hill. Other women have accused Thomas of sexual harassment as well; one of them, Angela Wright-Shannon, recently called for his impeachment, too.

Impeachment and removal of a federal judge, including a Supreme Court justice, requires meeting a high political bar. Just as with presidents, a majority of the House must approve an indictment to impeach, and a two-thirds supermajority of the US Senate must convict for the judge or justice to lose their office.

There is considerable precedent for impeaching and removing lower-level federal judges. For Supreme Court justices, the number of precedents is much smaller: There is one case in which a Supreme Court justice was impeached but not removed, and no other examples.

Here is how the process works and what previous efforts have taught us about it.

How impeaching judges works

As a 2010 report by Elizabeth Bazan for the Congressional Research Service explains, Article II, Section 4 of the Constitution provides for the removal of “the President, Vice President, and all civil Officers of the United States … on Impeachment for and Conviction of, Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors.”

The term “civil officers” is not defined in the Constitution, and Bazan notes that with one exception (US Sen. William Blount, one of the first two elected from Tennessee in 1796) every person impeached so far has been an executive or judicial branch official. The Senate ultimately decided that Blount was not a “civil officer” and acquitted him on that basis.

By contrast, Bazan writes, “the precedents show that federal judges have been considered to fall within the sweep of the ‘Civil Officer’ language.” The House has, in the course of federal history, impeached 13 judges, and the Senate has convicted and removed eight. Of those convicted, seven were district judges. The other was Robert Archbald, who served on the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit and the now-defunct United States Commerce Court until his 1913 removal.

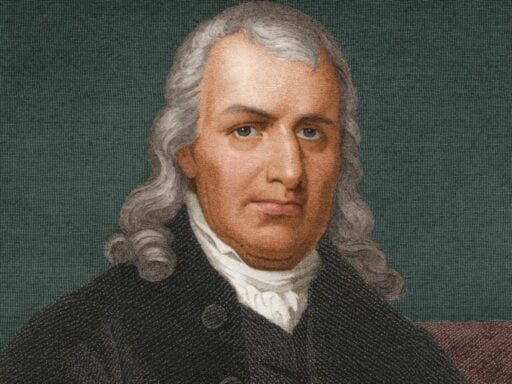

The four acquitted included three district judges and Supreme Court associate justice Samuel Chase. Chase, a Federalist appointed by George Washington, was the only Supreme Court justice to be impeached, in a highly politicized attempt by Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republicans to take out a political enemy (albeit an enemy who was himself highly partisan, and the charges against whom weren’t wholly baseless).

The 13th judge, Samuel Kent, of the District Court for the Southern District of Texas, resigned before he could be convicted.

As Bazan notes, this is something of an undercount. She lists 23 other judges who have had “impeachment resolutions, inquiries, or investigations … that, for various reasons, did not result in articles of impeachment being voted by the House.”

What judges get impeached for

Focusing on the five most recent cases in which judges were impeached, from 1986 to present, impeachment and removal typically comes in cases of clear, criminal wrongdoing. That makes sense given the incredibly high bar in the Senate required for removal; accusations perceived as partisan are unlikely to reach 67 votes.

Harry Claiborne was impeached and removed in 1986, two years after receiving a two-year prison sentence for falsifying income tax returns. Alcee Hastings, who has since become a representative from Florida, was removed in 1989 for receiving a $150,000 bribe to reduce prison sentences for members of the mob. He had been acquitted of this charge in normal criminal court, but a special committee of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals concluded that Hastings had committed perjury and tampered with evidence in the case to secure his acquittal.

Walter Nixon was removed in 1989, three years after receiving a five-year prison sentence for perjury. Both he and Hastings challenged the procedures for their impeachments in Court, but in the case of Nixon v. United States, the Supreme Court concluded unanimously that it had no authority to review the impeachment process, as impeachment trials are the sole province of the Senate.

Before his impeachment in 2009, Samuel Kent pleaded guilty to obstruction of justice and sentenced to 33 months in prison, for lying about his sexual abuse of female employees. G. Thomas Porteous, alone among the recent impeachment cases, was not criminally convicted in federal court before his 2010 impeachment by the House and conviction by the Senate.

After an FBI and federal grand jury investigation, the Department of Justice had declined to press charges for, among other reasons, concerns about statutes of limitations. He stood accused of accepting bribes from lawyers with business before him, and of failing to recuse himself from cases involving people who allegedly bribed him.

These are all very different from the Kavanaugh case

If one takes the five impeachment cases in recent decades as a model, Kavanaugh’s conduct (and Thomas’s) does not appear similar. While Kent’s case involved sexual misconduct, he had also already been criminally convicted, whereas Maryland prosecutors show little interest in pursuing charges against Kavanaugh in the Ford case. There is little indication that federal prosecutors believe he committed perjury in his statements about the judicial memos.

These five most recent cases involved judges whose wrongdoing was recognized by both political parties in Congress, and who had few if any defenders in the Senate. Kavanaugh and Thomas both have enthusiastic supporters in the Senate, and even if Democrats retake both houses of Congress, it’s doubtful that enough Republicans will defect from Kavanaugh to make removal viable.

That said, there is no clear definition of a “high crime or misdemeanor.”

“The precedents in this country, as they have developed, reflect the fact that conduct which may not constitute a crime, but which may still be serious misbehavior bringing disrepute upon the public office involved, may provide a sufficient ground for impeachment,” Bazan writes, citing the case of Judge John Pickering, who was convicted on charges including mishandling cases in his capacity as a judge. That’s not a criminal offense, but the House and Senate considered it sufficiently serious to justify impeachment.

“What constitutes an impeachable offense,” Bazan concludes, “is less than completely clear.” The best answer might be that an impeachable offense is whatever the House and Senate think it is.

Author: Dylan Matthews