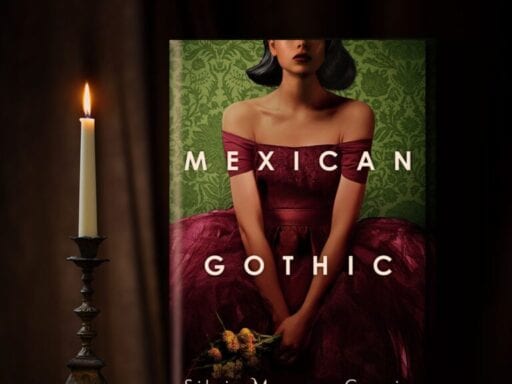

A cosmopolitan Mexico City socialite navigates the provincial horrors of an English manor in Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s new novel.

There is something monstrously fecund, something growing and decaying and rotting, in High Place, the center of Silvia Moreno-Garcia’s new novel Mexican Gothic.

High Place is an English-style manor house perched above the old Mexican mining town of El Triunfo. As the novel opens in the 1950s, the silver mine is closed and the town is miserably impoverished. But the Doyles, the English family who operated the mine, still reign in crumbling and isolated splendor over everything.

In High Place, mold crawls across the walls. Electricity is rationed, so everyone must walk around with gas lamps or candelabras. The garden is planted in soil shipped over from Europe. Spanish is forbidden, and English is the only language spoken. Everything smells of rot. Into this creepy, insular atmosphere comes the high-spirited young socialite Noémi.

Noémi does not particularly care to leave her fashionable life in Mexico City behind, but she’s on a rescue mission: Her cousin Catalina married into the Doyle family and was whisked away to High Place before her own family had a chance to properly meet the Doyles. Now Catalina’s letters are laced with horror.

Catalina thinks her husband is poisoning her. She sees ghosts walking through the walls. “I am bound, threads like iron through my mind and my skin and it’s there. In the walls,” she writes. Noémi is in High Place with a job to do: Find out whether Catalina is insane or merely frightened, and in either case, figure out how best to help her.

But at High Place, the Doyles keep Noémi away from Catalina. The cousins are allowed to meet only under close supervision, with the Doyles claiming that Catalina needs rest and some kind of mysterious treatment. They tell Noémi that Catalina is recovering from tuberculosis.

In between visits with her cousin, Noémi busies herself exploring the house. She finds more mold, and volume after volume of books on eugenics. At dinner, the Doyle patriarch Howard remarks to Noémi that she is “much darker” than her cousin. “What are your thoughts on the intermingling of superior and inferior types?” he asks her.

At night, Noémi begins to dream strange dreams: of sex with Catalina’s husband that is both unwanted and deeply pleasurable; of a woman made of gold who tells her to open her eyes; of murder and constrain and rot, rot everywhere.

Slowly and inexorably, the dread builds.

The gothic in this book goes well beyond surface-level tropes

Moreno-Garcia is playing with great dexterity here with the conventions of the gothic house novel: all these women roaming a decaying mansion in their nightgowns, clutching candelabras; all these sinister men with deep, dark, terrible secrets. And just to drive it all home, the mold on Noémi’s bedroom wall is yellow and it moves, like the yellow wallpaper come to monstrous life.

But the true source of the gothic in Mexican Gothic — the awful force that creates restraint against which the gothic heroine must fight; the source of the rot — is colonialism. The Doyles came to El Triunfo to take the silver from its earth and have never cared that they exploited its people, or that they continue to do so still. Their only concern is personal enrichment. Howard refers to his former mine workers as “mulch.” To save herself and Catalina, Noémi must push back against the forces of an old imperial power — and against the creeping, insidious pleasure she knows it would bring her if she were to submit to it.

It’s the elegance with which Moreno-Garcia handles this metaphor that elevates Mexican Gothic above the level of didactic pastiche. This book is deliciously true to the gothic form, grotesque without becoming gross, and considered, always, in the way it thinks about power and its characters’ reactions to power. Read it with your lights on — and know that strange dreams might begin to haunt you, as they haunted Noémi.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More