Grace Dane Mazur’s new novel is a gorgeous anachronism.

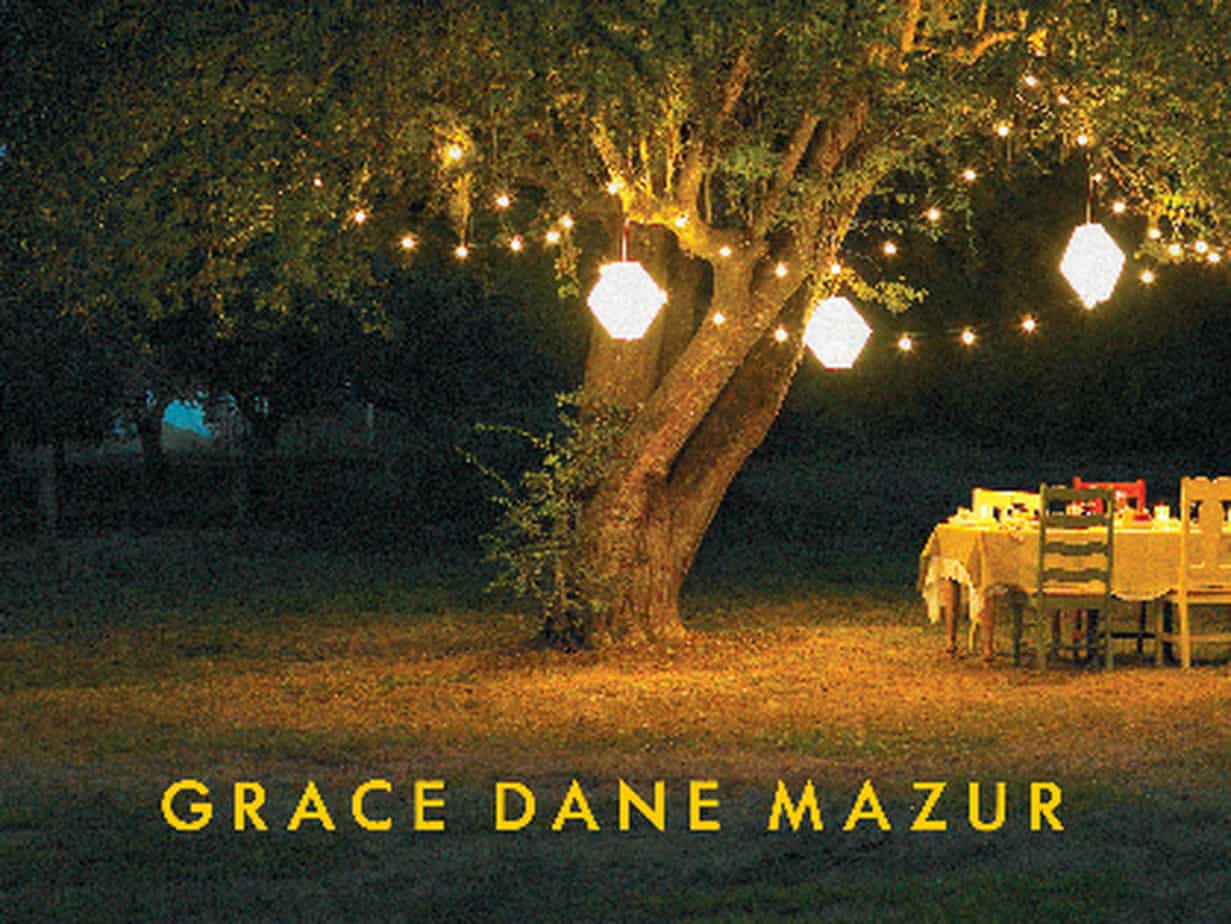

The Garden Party, a lyrical new novel by Grace Dane Mazur, is a modernist throwback of a book. In our age of realistic novels and high-concept dystopias, it is a lovely, shimmering anachronism.

The titular garden party is a rehearsal dinner, meant to unite the bohemian intellectual Cohens (groom’s family, hosting) with the wealthy conservative Barlows (bride’s family, visiting). The Cohens are academics and poets who like to talk about art and true love and the nature of time; the Barlows are lawyers who like to discuss current events and gossip about their adulterous affairs. Each side regards the other with skepticism and restrained disgust, but Mazur, clearly, is on the Cohens’ side.

Mazur follows the party over the course of the day, beginning with the flower selection — shades of Mrs. Dalloway — all the way through to the redemptive, baptismal end of the evening. Each of her 25 characters gets their own inner monologue, from the pre-verbal 3-year-old to the Alzheimer’s-ridden grandfather, with their thoughts rendered in long streams of free indirect discourse.

The conflict here can feel reductive. The Barrows are cartoons of the small-minded wealthy — “It’s like a third-world country here,” says one, upon learning that the Cohens subscribe to neither the Economist nor the Wall Street Journal. “Do you think the dinner will be acorns and grubs?” — while the Cohens, in their just-as-wealthy bohemianism, are endlessly warm and empathetic. The family matriarch, Celia, imagines her party as having “emotional fields hovering among the guests” that “stood out for her like strands of colored smoke,” so that “not only the erotic forces, but all the other psychic currents she saw as neon strands of cat’s cradles, glowing as though they were external neurons, which — if one paid enough attention — one could untangle and weave into a narrative of the emotions.”

For some readers, Celia’s neon strands of light might come off as hippy-dippy pretension, but in the world of The Garden Party, they signal her ability to treat even the cold and judgmental Barrows as human beings worthy of respect. The Barrows are on the side of the Wall Street Journal, but Celia, our heroine, is on the side of empathy and art. It’s not a fair fight.

Still, as unbalanced as the conflict is, it’s beautifully rendered, all seething dislike beneath polite, desperate small talk. “Refrigerators are harassing me,” one Barlow says to a Cohen, while thinking, “What could she talk to this man about? She was running out of appliances.” The unhelpful Cohen, thinking about his work, replies, “Do you think that intelligence is connected to beauty?”

The polyphony of voices in this book can overwhelm, with the Barlows in particular blending into a single amorphous mass of callow cynicism. (Mazur has provided a seating chart with notes on each character at the front of the book; it does not help.) But Mazur’s prose is so vivid and melodic that it’s easy to let her language sweep you away. Ignore the characters, who are a little dull anyway; listen to the words, which are stunning. Here, herbs are cut with “ecstatic chopping noises,” while the tablecloth “flutters as though alive.” You can smell the chopped mint and see the tablecloth blowing in the wind.

As the book goes on, Mazur plays repeatedly on the rich symbology of the garden in which the party is taking place, so that it becomes an Eden, a fairyland, a Jungian forest of the subconscious. The children run away to form their own shadow dinner party, echoing the actions and the rituals of their adult counterparts to the second, and the garden pond becomes a site of death and life and marriage and baptism.

It is all very Virginia Woolf, and a little bit E.M. Forster too; in places, The Garden Party feels like an old-fashioned formalist experiment. Here, theme and language and allegory are paramount, and characters are dull devices employed to get us to the good stuff. That balance would not work at all if the good stuff were not top-notch — but thanks to Mazur’s deft hand, it is. This is a rich and lovely book.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png