Experts warn there’s no off-ramp to lower tensions right now.

India and China, the world’s two most populous nations, each armed with nuclear weapons, are in the middle of their most severe crisis in decades — and it’s unclear how both nations will step back from the brink.

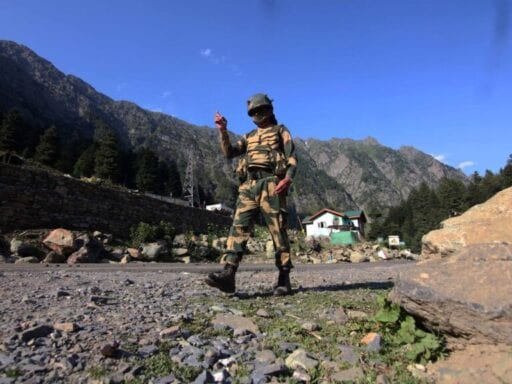

At least 20 Indian troops were killed in a skirmish with Chinese forces in the Galwan Valley, a contentious territory in the high-altitude Ladakh region, on June 15 and 16, according to the Indian Army. Meanwhile, there are unconfirmed reports that there were 43 casualties among Chinese troops. Still, it’s the deadliest clash between the two countries on the border since 1967.

For about 80 years, India and China have quarreled over a roughly 2,200-mile frontier spanning the Himalayas, occasionally going to war over their competing claims. Despite 20-plus rounds of negotiations, they haven’t come close to agreeing on most of the boundaries, providing a continuous source of tension between Beijing and New Delhi.

The latest flare-up began last month in the Galwan Valley. India’s government said that earlier this month, unprovoked Chinese troops threw rocks at Indian soldiers in the western Himalayas. Beijing counters that claim, instead blaming Indian forces for illegally walking into Chinese territory. Whatever the reason, a combined 100-plus soldiers from both sides sustained injuries during two skirmishes on May 5 and May 9.

There were a couple of other small fights leaving dozens injured at two points along the 2,200-mile border in recent weeks. Even so, experts hoped that would be the worst of it, hoping there wouldn’t be a repeat of the 1967 border fight that led to hundreds dead.

But now the ongoing spat in Ladakh has turned deadly.

Earlier on Tuesday, the Indian Army said three soldiers died during a “violent face-off” with Chinese troops. It turns out that was a very low estimate, with the army increasing the death toll to 20 troops hours later.

Importantly, Indian forces note that “sub-zero temperatures” played a role in why some soldiers “succumbed to their injuries.” Chinese forces, meanwhile, also noted their troops suffered “casualties,” but it’s unclear if they were wounded or if some died.

…and exposed to sub-zero temperatures in the high altitude terrain have succumbed to their injuries, taking the total that were killed in action to 20.

Indian Army is firmly committed to protect the territorial integrity and sovereignty of the nation. (2/2)— Sushant Singh (@SushantSin) June 16, 2020

There’s still a lot we don’t know. For one, it’s not clear how the fight started. Some reports noted there was an avalanche or that both sides fought with sticks in a melee, and both sides are blaming the other for instigating the skirmish by crossing the disputed border.

“India is very clear that all its activities are always within the Indian side,” read a statement from India’s foreign ministry. “We expect the same of the Chinese side.”

Indian troops crossed the disputed border “and conducted illegal activity, and deliberately launched provocative attacks, triggering violent physical conflicts between the two sides, resulting in casualties” the Chinese military claimed.

Slightly amended translation of the PLA Western Command’s statement on the Galwan River clash. Not my day job. pic.twitter.com/S45ccEt5h6

— M. Taylor Fravel (@fravel) June 16, 2020

The facts, of course, matter. But either way, experts say the ramifications will be the same: These two powers will struggle to stand down from this fight. “There’s every likelihood that this could get worse,” Sumit Ganguly, an expert on India’s foreign policy at Indiana University Bloomington, told me. “There’s no easy off-ramp.”

Most experts agree. “The best-case scenario is they use this incident as a wake-up call to shock them into solving this [border fight] once and for all,” Vipin Narang, an expert on Indian forces at MIT, told me. “The worst case is the nationalists push to escalate and it’ll be a long, long summer.”

He noted that China has much stronger forces overall but that India has amassed enough military force at the border that it can rival Chinese troops at that frontier. Which means “once the bullets start flying, it’s unclear how it’s going to go,” he said.

The current situation is about much more than the decades-long border dispute. It’s also about the increasingly bitter rivalry for power in Asia.

China, especially under President Xi Jinping, frequently uses its military might to bully neighbors and claim more territory for itself, including along the mountainous frontier. India, meanwhile, has been building roads and airstrips along its border with China in an attempt to exert more control, piquing Beijing in the process.

After tensions simmering for years, they have officially boiled over.

The long China-India border fight, briefly explained

The seeds of the current flare-up were planted during British colonial rule of India.

In the late 1800s, the British drew two borders to formalize the yet-undefined frontier between India and China, one in the “Western Sector” in Kashmir and the other thousands of miles away in the “Eastern Sector.” But China — along with a then-independent Tibet — didn’t agree to the British proposals, leaving demarcation an open question for decades.

The border skirmishes are not new to the 3,488km (2,167-mile) frontier between India and China, most of which remains disputed and undemarcated. | Great map work by @AliaChughtai pic.twitter.com/ScW0ai6LD0

— Saif Khalid (@msaifkhalid) May 27, 2020

After India gained independence from Britain in 1947, its leaders said the British-drawn boundaries were firm and claimed some of the disputed territories — including the Aksai Chin region near the Galwan Valley — for itself. Though it initially accepted some of India’s stances, China changed course over time. In 1957, for example, the Chinese built a road in the Western Sector through parts India said it controlled.

Ties between the two countries remained cordial, but they frayed over the next few years in part due to the border problem. Skirmishes between Indian and Chinese patrols first began in 1959 but grew more frequent and violent until October 1962, when Chinese troops invaded India over the disputed border.

After 32 days of fighting, China had gained more control in the Western Sector and pushed the ill-trained and ill-equipped Indian troops back about 12 miles in the Eastern Sector. It was a humiliating loss for India that haunts the country to this day.

To semi-officially separate the two, a “Line of Actual Control” (LAC) was finally adopted by both countries, marking the disputed claims along the thousands of miles of land — but it was by no means definitive. Much of the LAC was, and remains, porous, noncontiguous, and unmarked, and thus did little to resolve the competing claims between the two countries. The two nations don’t even agree on the actual length of the LAC.

Simmering tensions have persisted despite the pseudo-border in place.

Just days before Xi’s first visit with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in September 2014, over 200 Chinese troops entered Indian territory in the western Himalayas to build a road. Indian troops challenged the Chinese soldiers, pushed them back, and reportedly destroyed the road.

In 2017, Chinese engineers tried to build a road through the Doklam plateau, also an area in the Himalayas claimed both by China and Bhutan, a small country wedged between the two larger powers. Indian troops on their side of the border directly intervened and pushed the crew back.

Weeks of negotiations between Beijing and New Delhi finally ended with India agreeing to pull back troops from the area and China agreeing to end its project (though Chinese leaders vowed to keep patrolling the area). Satellite images released the following year by the independent intelligence firm Stratfor showed that both sides had continued to build up their forces near Doklam, with India placing attack helicopters at an airfield and China deploying a fighter jet and missile system to its airbases.

That activity continues to this day. “Both China and India are ramping up activities in the Himalayas — building infrastructure, sending military assets — to have more control in the region,” Adam Ni, a board director of the China Policy Center in Australia, told me last month.

The incursions continue, too. According to the Indian government, China’s forces crossed into Indian territory more than 1,000 times between 2016 and 2018. However, they engaged in a massive deadly clash since 1967 and neither side had even shot at the other since 1975, abiding by agreements both countries signed in the 1990s to not use weapons in these skirmishes.

That helped lead to a fragile peace — and that peace is broken now.

This is really all about China and India’s larger rivalry

There’s a lot more to this border dispute, according to the experts I spoke to. Sure, it’s obviously about the years of animosity built up at the undefined frontier. But it’s really about each side sending a larger message to the other.

China wants greater control along the LAC and parts of South Asia, but India’s size and coziness with the United States make it hard for Beijing to achieve that. Starting a fight along the border “is a way for Chinese to signal to the Indians that they can make life pretty bad,” Ganguly told me in May.

India, meanwhile, wants to send its own signal that it won’t be pushed around by its powerful neighbor, especially in the same area where it lost a brutal war just a few decades ago.

And New Delhi wants to stake its claim even further as the country invests billions in infrastructure in the region, aiming to build 66 roads along the Chinese border by 2022. One of those roads connects to a military base in the Galwan Valley.

As long as the regional rivalry continues and the border issues remain unsolved, skirmishes will likely persist. “This is a new normal that we’re likely to see play out a lot in the coming months and years,” Michael Kugelman, an India expert at the Wilson Center in Washington, said last month.

The good news, experts noted at the time, was that neither side actually wants a full-blown war. Both nations, of course, have their hands full dealing with the coronavirus pandemic. Beijing is also preoccupied with growing animosities with the US and seizing more control in Hong Kong, while New Delhi knows that challenging China militarily would likely end badly for India.

That still holds, as a war between two large nations with nuclear weapons could get out of hand very quickly. “Neither side has an incentive for this to escalate,” said MIT’s Narang. The problem is that nationalist voices in both countries will likely call for revenge, possibly putting pressure on Xi and Modi to respond forcefully.

In other words, there isn’t a clear off-ramp right now — and it could all get worse before it gets better.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Alex Ward

Read More