A slew of new changes has drawn the ire of celebrities and regular users alike. But hating Instagram is nothing new.

For as long as Instagram has existed, people have complained about it. Hating Instagram — and to an even greater extent its sister site, Facebook — is among the few opinions that a majority of the internet seems to share, but over the past few weeks, the volume has been turned up rather significantly. Last Thursday, Instagram head Adam Mosseri addressed the criticism in a video that, naturally, resulted in even more of it.

The most recent controversy stems from Instagram’s parent company Meta (previously called Facebook) and its propensity to copy the features of up-and-coming social media platforms. Right now, Instagram’s biggest competitor is TikTok, which serves users an infinite feed of personalized trending short-form video and whose popularity has skyrocketed just as Facebook’s has begun to wane. In an effort to replicate its success, several of the latest Instagram and Facebook updates prioritized “recommended” videos (i.e., from random users across the platform as opposed to someone you already follow), among other things that made people very stressed out. “The new Instagram update really understood what I was looking for: none of my friends’ content, reposted TikToks from meme accounts I do not follow, 100x more ads, everything played at full volume against my will,’’ summarized one viral tweet.

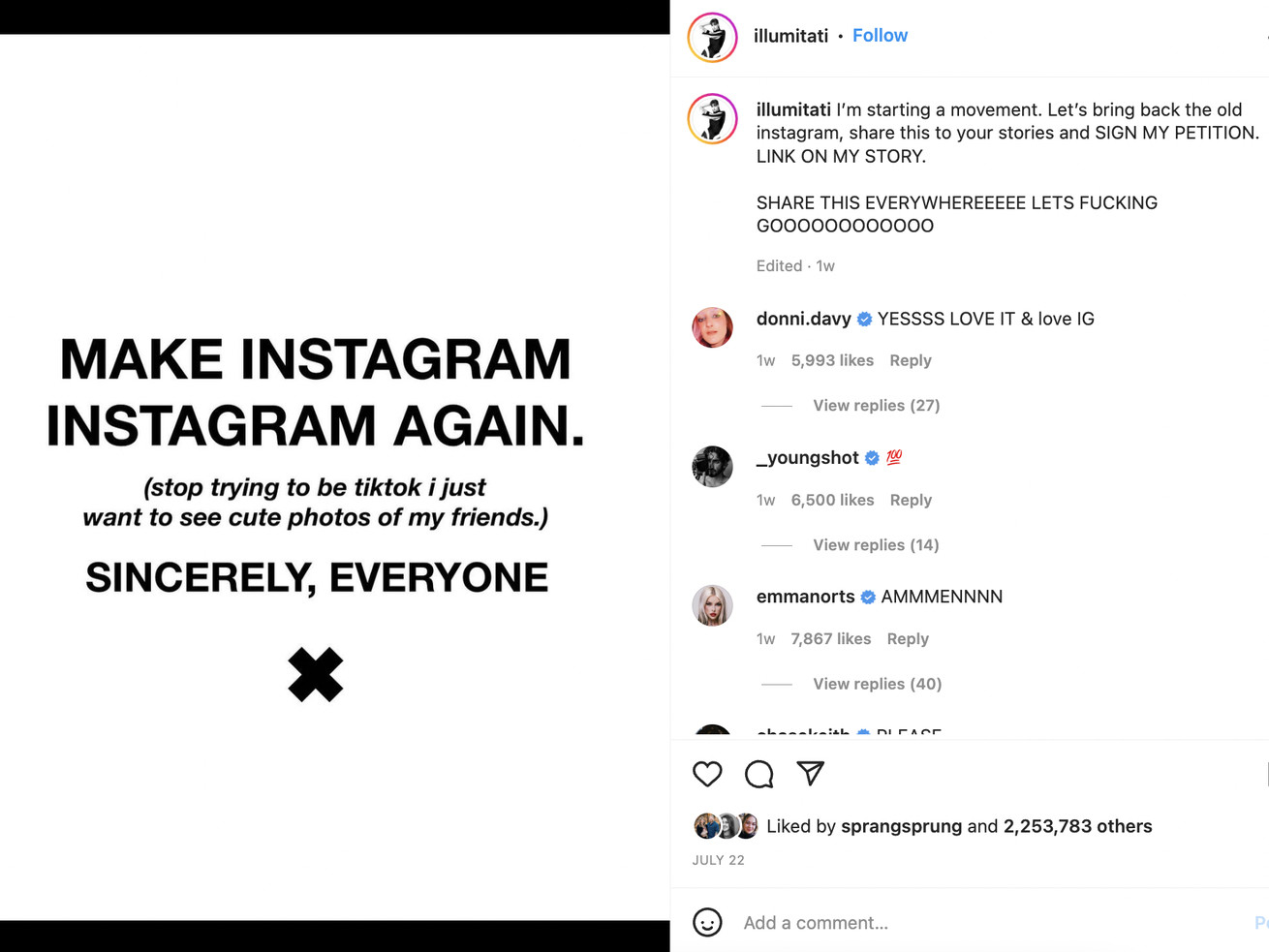

The furor reached a fever pitch when a post by photographer Tati Bruening went viral, demanding, “Make Instagram Instagram Again,” and “stop trying to be TikTok, I just want to see cute photos of my friends. Sincerely, everyone.” The post, which now has more than 2 million likes, was reshared by some of Instagram’s most powerful users, namely, Kim Kardashian and Kylie Jenner.

Concurrently, dozens of meme creators staged a rally outside of Meta’s New York headquarters on July 23 in what they called an “Instarrection.” Though the event was not focused on the new updates and instead protested Instagram’s nebulous, inconsistent moderation practices, which often result in accounts being taken down for unclear reasons, it reflects a growing sentiment among Instagram users that Instagram is getting worse.

By all accounts, Meta’s shareholders agree. Earlier this year, Meta announced that users were spending less time on its platforms and that it expected revenue growth to slow, causing its stocks to plunge 26 percent, losing $232 billion in the process, and becoming the steepest one-day decline for a single stock in US history. The mood, on Instagram and within its headquarters, is bleak: This summer, CEO Mark Zuckerberg has limited spending at the company while pressuring employees to “operate with increased intensity” and threatening to cut low performers. “There are probably a bunch of people at the company who shouldn’t be here,” he told staff.

Being mad at Instagram is sort of like being mad at the president: Venting your frustrations about it is both a cathartic and logical response to a seemingly insurmountable problem, the problem of too much power in the hands of too few people. In 2019 I wrote about how, within a decade of its existence, Instagram broke our brains, training us to view one another as commodifiable brands and splinter ourselves in two. In 2021 I wrote about how visual-first social platforms can make as many changes as they like in response to the knowledge that their products harm users’ self-esteem, but they will never solve the problem they created. In 2022 I wrote about how Instagram’s incessant fixation on video ends up worsening the content on the site while also dramatically increasing the workload required to succeed on the platform. Instagram has made dangerous misinformation look adorable and beautiful destinations unbearable; it has lied, repeatedly, and yet people feel as though they have nowhere else to go.

Last week, Instagram caved, slightly, to the growing chorus of criticism. In an interview with tech reporter Casey Newton, Mosseri said that the app would phase out one of the recent redesigns it had been testing while also temporarily showing users fewer “recommended” videos in the feed. Yet the changes aren’t permanent: By the end of 2023, Zuckerberg said that the number of “recommended” posts on Instagram will more than double. Mosseri attributes this change to a shift in what news feeds are for. “In a world where more of the friend content has gone from feed into stories and DMs, I think that feed is going to become more public in nature,” he said.

For the average Instagram user, the kind that would never describe themselves as a “creator” despite the growing number of people who do, this won’t come as good news. As one venture capitalist put it, speaking to the Washington Post, “There’s a war between people who want Instagram to be more like Snapchat and people who want it to be more TikTok. Right now the former group is larger and louder.”

The problem is that Instagram doesn’t actually care as much about that group as it does about the other: Instead, Instagram sees the best way to grow a loyal, exceedingly active user base as dangling the prospect of getting famous in front of them. Video, then, is only a means to that end. “I think one of the most important things is that we help new talent find an audience,” Mosseri added. “If we want to be a place where people push culture forward, to help realize the promise of the internet, which was to push power into the hands of more people, I think that we need to get better at that.”

Curiously, some of the buzziest new social apps as of late — BeReal, NGL, and Locket — have nothing to do with fame at all. On BeReal, users see spur-of-the-moment photos from mutual contacts, while Locket allows them to share pictures directly to each other’s home screens. NGL, meanwhile, is an Q&A app that became a popular game on Instagram Stories this June, where those with access to a link could ask anonymous questions of the poster. None of them promise the total digitization of the social circle that Facebook and Instagram do, nor do they offer the possibility of virality.

Instagram, meanwhile, has decided it should be everything to everyone. As Meta continues its pivot towards the so-called “metaverse,” an as-yet-mostly-theoretical vision where bitmojis have meetings (?), it seeks to be even more. What remains in question is whether America’s antitrust laws will actually be enforced to prevent Meta from employing the same monopolistic practices there, too, and to what extent Meta can continue to grow its extensive, unprecedented authority over the internet. In all likelihood, however mad everybody is at Facebook and Instagram now, it’s only going to get worse.

This column was first published in The Goods newsletter. Sign up here so you don’t miss the next one, plus get newsletter exclusives.

Author: Rebecca Jennings

Read More