How can the party best limit backlash from voters?

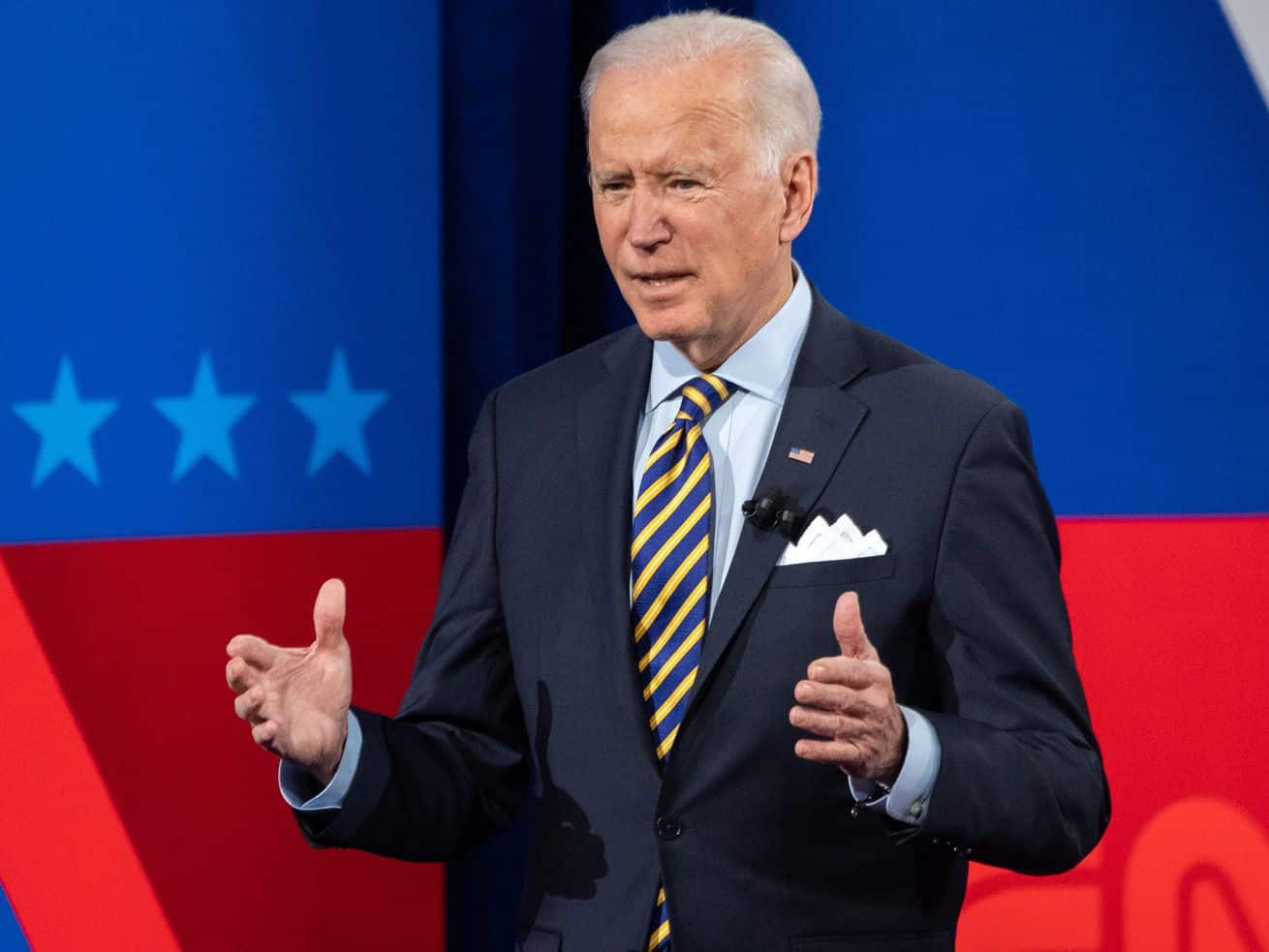

Once congressional Democrats pass a large Covid-19 relief bill, using the budget reconciliation process to avoid a Republican filibuster, the big question is how much further President Biden’s legislative agenda will go.

The progressive wing of the party has a long and varied list of things they want to get done with their newfound congressional majorities — tackling areas ranging from climate change to immigration to health care to voting rights to even adding states, among many others. Scrapping or otherwise reforming the Senate filibuster would likely be necessary to get many of these done. And some argue that, if Democrats want to keep their narrow congressional majorities in 2022, they need to get as much of this done as possible.

“What history tells us is that, when Clinton won in ‘92, two years later, the Democrats didn’t do as much as they should have. They got swept out by the Republicans,” Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) said on CNN last month. “If we do not respond now, yes, I believe, two years from now, the Republicans will say, ‘Hey, you elected these guys, they did nothing, vote for us,’ and they will win.”

Moderates have a different view. They believe that the best way to maximize Democrats’ chances of winning in 2022 is to focus the agenda more narrowly on voters’ main priorities — pandemic relief and the economy — and set aside the more polarizing items on progressives’ wish list. And they fear that an overly broad agenda will instead inflame voter backlash.

“If going super-sized was the thing that voters wanted, we would be entering year five of the Sanders presidency,” says Matt Bennett of the centrist Democratic think tank Third Way. “Instead we’re entering year one of the Biden presidency. Because he understands that we have to go big to respond to these huge crises which he has, but we have to connect it to people in ways that feel real and make a difference.”

The risk of backlash is real. In every midterm election since World War II, the incumbent’s party lost House seats, and in most they lost Senate seats too. Democrats’ control of Congress already hangs on a knife’s edge — a net loss of just five House seats and one Senate seat would give Republicans majorities.

If you’re wondering why senators, like Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV), oppose abolishing the filibuster, the fear of backlash may be one major reason. Essentially, the filibuster constrains Democrats’ agenda to either what they can pass through the special budget reconciliation process or what they can get Republican support for. At least in theory, this would make the party less likely to overreach — by sharply limiting what they can even do.

In contrast, liberals feel that, by keeping the filibuster, Democrats are tying their own hands, preventing themselves from passing other policies that are both badly needed and could help them win. They’re pushing for more, but in the end the choice about whether to go bigger will come down to the party’s moderates.

Backlash is likely. But is it inevitable?

There is some disagreement in the Democratic Party about the substantive merits of a broad progressive agenda. But when it comes to the politics of such an agenda, the question boils down to one of voter backlash — and specifically, about whether backlash is inevitable, or about whether Biden has a real shot of mitigating it with good strategic choices.

Historically, midterm elections have been extremely unkind to incumbent presidents’ parties, but Biden may have some factors working in his favor if the pandemic abates and the economy gets a boost from that abatement.

But Biden faces the additional problems of both chambers’ maps favoring Republicans, in the House due to gerrymandering (a new round of which is coming before the midterms), and in the Senate because white rural voters are spread out among more states. For the Senate’s 2022 map, Democrats are tasked with defending swing-state seats in Georgia, Arizona, and Nevada, while their best pickup opportunities are in Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, and North Carolina — all states that were more Trump-leaning than the national popular vote in 2020.

That is: For Democrats to keep their congressional majorities, Biden doesn’t just need to do what’s popular nationally, he needs to do things that will be popular in states and districts that lean to the right.

The 2022 midterms aren’t just important for the short term. A disastrous showing could put Democrats in such a deep hole that retaking majorities would become forbiddingly difficult for years to come. The 2024 Senate map, for instance, looks challenging for the party, with red state incumbents Manchin, Jon Tester (D-MT), and Sherrod Brown (D-OH) all up during a presidential year. So though midterm losses might be tough for Biden to avoid, limiting the size of those losses could be important for Democrats’ hopes in the future.

Matt Grossmann, a professor of political science at Michigan State University, argues that Democrats’ midterm losses tend to be bigger when they succeed in passing an ambitious agenda. “If anything, there’s a negative relationship between the amount of major legislation that passes and what happens in the next election for Democrats,” Grossmann says. “There’s also a negative relationship between the amount of liberal policy that passes and the performance in the next election.”

Grossmann cites 1966 (the first midterm after LBJ’s Great Society, encompassing civil rights and social welfare legislation), 1994 (Bill Clinton’s first midterm, after he had passed a controversial economic bill and then failed to pass health reform), and 2010 (Barack Obama’s first midterm, before which he had passed stimulus and health reform and tried but failed to pass a cap-and-trade bill), all of which saw massive Democratic losses.

One counterexample is that FDR’s Democrats did quite well in his first midterm in 1934, amidst the Great Depression and New Deal. But, Grossmann argues, “to the extent that we have evidence, it’s closer to the opposite of that story that doing a whole bunch of things helps” the Democratic Party in the midterms.

What causes a bigger backlash?

So doing a lot can be risky for Democrats, but we’re in the midst of a pandemic that requires bold action to address — doing nothing is not an option. Happily for Biden, his first major priority is quite popular — according to a recent Quinnipiac poll, 68 percent of respondents say they support Biden’s stimulus proposal and only 24 percent say they oppose it.

The real strategic debate is about what to do after the stimulus. I spoke to Eric Patashnik, a political scientist at Brown University who is writing a book about backlash, to get a better sense of how it might be avoided.

Patashnik stressed that Democrats’ main concern should be making “good public policy” rather than legislating only with short-term electoral consequences in mind. But, he said, “I do think the risk of backlash is important to recognize and acknowledge and manage.” Sometimes, he said, a certain policy initiative is “a risk that’s worth taking, sometimes it’s a risk that’s not worth taking because the policy gains aren’t worth the political blowback.”

And according to Patashnik, there are several features that appear to make certain policies more likely to produce backlash, including:

- When they impose near-term visible costs (such as tax increases)

- When they threaten the social identities of groups (say, religious beliefs, or challenges to the status of groups like police officers)

- When they generate resentment about the provision of benefits to “undeserving” groups (for instance, conservative backlash to welfare or benefits for undocumented immigrants)

- When they challenge the power of groups that are highly dependent on or attached to existing arrangements (this applies to a myriad of special interests)

- When policies don’t represent the views of average voters (such as George W. Bush’s Social Security privatization effort, and House Democrats’ push for the cap-and-trade bill rather than staying focused on recovery from the Great Recession)

“There are tremendous incentives for policy overreaching, to prioritize policies that are more important to the base than to average voters, due to close party balance and the uncertainty of future control,” says Patashnik.

None of this, Patashnik hastens to add, necessarily means ambitious policies that could match these descriptions shouldn’t be pursued if Democrats think they’re substantively so important that they’re worth the possible political consequences. He mentioned democracy reform and the protection of minority voting rights as examples. But it’s important to be clear-eyed about what the political consequences might be, rather than simply to assume that backlash won’t happen.

I also asked Patashnik about an argument made by the New York Times’s Ezra Klein, that Democrats need to pass “visible, tangible policies” to “create feedback loops,” so voters will receive and understand their benefits. This argument is essentially that Obama’s 2009-10 stimulus and health care bills were poorly designed because voters didn’t understand their merits until later if at all — in contrast to, say, the stimulus money the Trump administration sent out in 2020.

“I do think the political science evidence is stronger that creating positive policy feedbacks and reinforcing loops promotes policy sustainability over time and protecting measures against repeal, than that it’s going to guarantee immediate electoral gains,” Patashnik said.

Voters might like policies like Obamacare and want to prevent their repeal later, but they won’t necessarily reward the politicians who passed them. “Good policies can be bad politics in the short run,” Patashnik said. This fits with the story of Obamacare, which didn’t seem to help Democrats electorally until Republicans nearly took it away in 2017. (Sarah Kliff did extensive reporting for Vox on why Kentucky Obamacare enrollees ended up voting for Trump.)

Democrats are keeping the filibuster, and that settles the issue prioritization debate in the moderates’ favor — for now

Progressives have spent much of the beginning of the Biden administration pulling their hair out about why moderates like Manchin and Sen. Kyrsten Sinema (D-AZ) would agree to defend the filibuster, thus drastically limiting what Democrats can pass with their votes alone to whatever can get through the arcane budget reconciliation process. The pressure is already building to try and get them and other opponents of a Senate filibuster-ending rules change to reconsider, and this debate will likely dominate much of Biden’s first year.

The weird quirks of how the filibuster can only be evaded through budget reconciliation on particular issues (see Dylan Scott for more on that) are a historical accident. But they’re a convenient accident for the party’s moderate wing, which would prefer Congress’s focus to remain on the economy and pandemic relief, and other popular topics like infrastructure — which are passable through reconciliation — rather than moving on to other long-held Democratic ambitions.

Indeed, when I asked Bennett of Third Way whether Biden could achieve his preferred agenda through budget reconciliation — meaning, without changing Senate rules to end the filibuster — he said, “Absolutely, yes.” Not every single item in Biden’s proposal will survive, he said, but Biden “can achieve what he needs to achieve to protect Dems going into the midterms and also what he needs to achieve substantively.”

But those Democrats who believe that other issues that can’t advance through reconciliation, like immigration reform and voting rights, are crucially important will be immensely frustrated that the filibuster is restraining their agenda.

“Democrats are constantly arguing over whether they are talking about race and cultural issues too much, whether they are appealing to voters of color and/or white voters without college degrees at the expense of turning off either group, and whether they are tilting too far left or not far left enough,” Perry Bacon Jr. writes at FiveThirtyEight. “In a world where the filibuster remains as is, they are unlikely to pass the kinds of legislation that would benefit voters of color in particular (statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico, which have large populations of voters of color; voting-rights provisions; immigration reform), that relate to culture and identity (limiting gun rights, expanding abortion rights) or that lean fairly far to the left.”

More broadly, canny strategists may think that the main use of the filibuster for Democrats is in fact to protect them from their own base — because, in effect, it settles what would be a bitter debate over which liberal policies to prioritize, by saying that Senate rules give them only very limited options. The policies that can pass through reconciliation are also the sorts of policies they think are less likely to produce backlash. They also happen to be the sorts of policies that Joe Biden would prefer to focus on anyway.

This may, however, be too clever by half. To the extent that the filibuster limits Democrats’ ability to effectively respond to the pandemic and help the economy recover, it could hurt the party’s chances in 2022. Additionally, progressives are onto this game, want the filibuster gone, and correctly understand that Democrats could get rid of it with a simple majority vote if they all agree. The question is whether Republicans will end up giving them a pretext to do it — by blocking something all Democrats agree must pass.

Author: Andrew Prokop

Read More