Amy Coney Barrett, who is on President Trump’s short list, has written about how religious views and judicial views intersect — and sometimes collide.

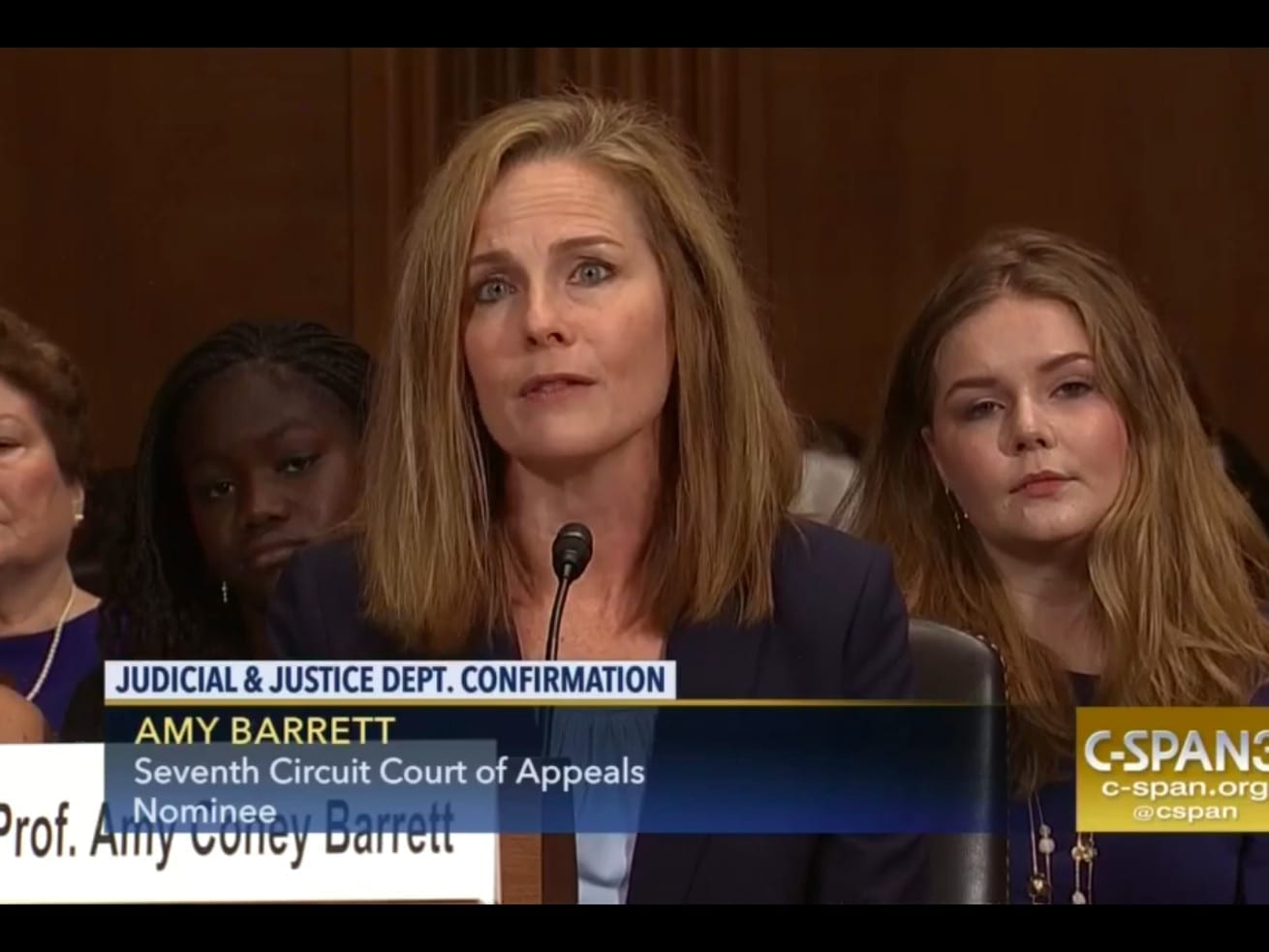

Twenty years ago Amy Coney Barrett, then a law clerk soon to enter the legal academy, co-authored an article called “Catholic Judges in Capital Cases.” The topics raised were intensely debated last year when she was nominated to serve on the federal bench and is sure to be debated again if President Donald Trump selects her for a Supreme Court post. Judge Barrett is reportedly on Trump’s short list to replace retiring Justice Anthony Kennedy.

Barrett wrote the article with John Garvey, her soon-to-be colleague at Notre Dame’s law school (he’s now the President of Catholic University), and in it they concluded that “Catholic judges (if they are faithful to the teaching of their church) are morally precluded from enforcing the death penalty.” The article is a model of serious scholarship — analytically precise, willing to take clear positions on important and controversial questions.

It became the focus of some quite misleading discussion during Barrett’s confirmation hearings, and is what led Sen. Dianne Feinstein (D-CA) to make her now notorious comment, “The dogma lives loudly within you.” That controversy aside, does the article raise questions that might fairly be explored in a nomination process — without lapsing into anti-Catholicism? I believe so.

Maybe Barrett’s views on the matters discussed in the article have changed since 1998, but asking her whether she still agrees with the article’s analysis seems well within bounds.

Barrett explored how Catholic judges should handle cases involving capital punishment

There’s some underbrush to clear away before we get to the heart of the question. First, the article deals with the obligations, in connection with capital punishment, of a person the authors describe as an “orthodox Catholic.” The authors equate “orthodoxy” with being “faithful to the teaching of the church on the subject.” A fair amount of the article deals with the church’s teaching on capital punishment, which is complex and not unequivocal. To somewhat oversimplify their careful analysis: They agree with the view that the church’s teaching strongly implies that administering the death penalty in the United States is immoral.

The matter of current interest is the obligation of an orthodox Catholic in connection with abortion, where the church’s teaching is clear and unequivocal; that removes one layer of complexity.

Second, the article argues quite correctly that the mere fact that a judge is a Catholic is not the basis for reasonable concern about his or her impartiality in death penalty cases, because the range of views among Catholics on the death penalty is rather wide, and even orthodox Catholics might not fully understand the church’s teaching. The case is different, I suggest, when one knows — or has quite strong reasons to believe — that a particular judge has orthodox Catholic views on the matter of abortion.

And that certainly seems to be the case with Barrett, whose religious convictions appear to be one of the primary selling points in her favor. They’re one reason she has such strong support among social conservatives, which in turn brought her to Trump’s attention.

She drew a distinction between two kinds of “cooperation with evil,” one worse than the other

Now, to the law review article. It draws upon long-standing Catholic moral teaching to distinguish between “formal” and “material” cooperation with evil. The authors define formal cooperation (the more direct kind) this way: “A person formally cooperates with another person’s immoral act when he shares in the immoral intention of the other.” In the article, the key example of formal cooperation is actually imposing a death sentence (as a judge might when presiding over a criminal trial).

Material cooperation, in contrast, occurs when an act “has the effect of helping a wrongdoer, where the cooperator does not share in the wrongdoer’s immoral intention.”

We’ve recently seen arguments based on the idea of material cooperation, when orthodox Catholics object to being forced to provide, or even subsidize, what they regard as abortion-related and contraception-related medical care: In their view, doing so amounts to material cooperation with evil. (What the law should do about that view is, of course, a different question, and I’m not concerned with it here.)

Barrett and Garvey’s article identifies some examples of formal cooperation in connection with the death penalty, such as actually administering the drugs at an execution and signing the document authorizing an execution — something a judge at a trial does. But the article devotes most of its analysis to questions about material cooperation, the morally grayer type.

Catholic teaching holds that formal cooperation is always immoral, but an appellate judge will almost never be faced with the possibility of formally cooperating with abortion. He or she will almost never have to sign a document authorizing an abortion for example. At most, the judge would say that the woman can have an abortion if she wants to, and that’s material, not formal, cooperation.

The article asserts, again in a way that’s consistent with Catholic teaching, that the morality of material cooperation depends upon the outcome of a “moral balancing test — weighing the importance of doing the act against the gravity of the evil, its proximity, the certainty that one’s act will contribute to it, and” — very important, I think — “the danger of scandal to others.”

Barrett asked what conclusions (moral and otherwise) reasonable observers would draw from a judge’s action

“Scandal to others” occurs when those “others” see the believer’s actions and infer that the “wrongdoing is not so wrong,” thereby “provid[ing] material for rationalization and self-deception by people tempted to undertake the same sort of wrong.”

The authors are uncertain whether an appellate judge’s sitting on a capital case amounts to material cooperation with evil because at least sometimes that judge will have to say that the law required a death sentence be imposed. But they conclude that sitting on a capital case concerning habeas corpus does not amount to material cooperation. That’s because in a habeas corpus case the issue is whether a trial judge did something that was within the range authorized by law — not whether the law required the death penalty.

So, for them, an orthodox Catholic judge should recuse himself or herself from imposing the death penalty but need not opt for recusal in habeas cases. They leave open the question about participating in direct appeals, where formal cooperation will be rare and the balancing required by the standard for material cooperation might allow participation.

They then examine whether the federal recusal statute requires in death penalty cases the recusal of a Catholic judge, merely by virtue of his or her church membership. They conclude that it does not.

The question of the “appearance of impartiality”

So what are the implications of the analysis for a judge who one knows is or has strong reasons to believe is an orthodox Catholic on the issue of abortion? The relevant recusal statute includes a provision dealing with “appearance of impartiality” and requires recusal if the judge’s impartiality “might reasonably be questioned.” The authors discuss this provision only in connection with a motion to recuse based solely on the judge’s general religious affiliation — identifying as Catholic, Jew, Mormon, or the like.

But, as I noted above, the case is different where the motion rests on assertions about a particular judge’s religious convictions rather than mere affiliations. Is it reasonable to believe that an orthodox Catholic would be subject to reasonable concerns about his or her impartiality in connection with actions that constitute material cooperation with evil?

We have to begin by observing that such a judge could conclude from his or her examination of the relevant purely legal materials that Roe v. Wade was mistaken as a matter of law and should be overruled. After all, many non-Catholic conservatives — and indeed some quite nonreligious conservatives and even some people who identify as liberals — think exactly that.

An orthodox Catholic judge’s views about material cooperation with evil might therefore play no role in his or her decision. The difficulty, though, is that someone observing the judge’s action — the reasonable person whose inferences matter when the “appearance of impartiality” standard is applied — can’t tell the difference between a decision to overrule Roe because the decision was not firmly rooted in the relevant purely legal materials, and a decision to do so because any other course would amount to material cooperation with evil, from the judge’s perspective.

Barrett and Garvey say a judge who makes a decision based on his religious views when he or she believes the purely legal materials dictate a different result is guilty of “cheating.” They condemn cheating; their position is that, rather than cheat, the judge should recuse himself or herself. But, if an orthodox Catholic judge does not opt for recusal, could an observer take the possibility of cheating to indicate that the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned?

When an orthodox Catholic judge sits on such a case, he or she may have antecedently concluded that affirming Roe v. Wade based on the purely legal materials would not amount to giving material assistance to the evil of abortion. But suppose the observer — again, the person we have to think about in connection with the “appearance of partiality” statute — concludes that conscientious application of the moral balancing test does mean that reaffirming Roe v. Wade would constitute giving material assistance:

The evil, from the orthodox Catholic’s point of view, is extremely evil (maybe even the ultimate evil), and though the evil is not at all proximate to the judge’s decision, that it will occur is nearly certain.

And the issue of scandal may be quite serious here: Others who see an orthodox Catholic judge affirming Roe v. Wade might conclude that abortion is not all that wrong. After all, if even such a judge can go along with a decision allowing abortions, how wrong could it be?

Barrett and Garvey’s article has a footnote dealing explicitly with abortion, but its implications for today are not entirely clear. The text to which it is attached reads, “If one cannot in conscience affirm a death sentence the proper response is to recuse oneself.” Quoting another scholar, the footnote reads, “‘Where there is no honest, legitimate alternative for deciding the case but to follow positive law supporting the right to commit an abortion,’ the judge should recuse himself. The abortion case is a bit easier.”

The implication seems clear but not entirely helpful: An orthodox Catholic judge should recuse himself or herself if the legal materials required affirming Roe. If an orthodox Catholic judge opts instead to cast a vote to overrule Roe, though, either the judge has decided that the purely legal materials support that vote or is willing to cheat. And the problem again is that the observer concerned with impartiality can’t tell which inference to draw.

Sen. Feinstein handled the issue very clumsily, but that doesn’t mean it’s not a legitimate one

The discussion of the article during Judge Barrett’s confirmation hearing was execrable. Either Sen. Feinstein’s staffers didn’t prepare her well or she disregarded or failed to understand their advice about what precise questions were raised by the article. The article’s arguments are complex and subtle, and the confirmation process is ill-suited to addressing arguments of that sort — particularly when what’s at issue are the arguments’ implications for highly charged matters not directly addressed in the original article.

Still, the article raises questions that can be asked in a confirmation hearing without devolving into anti-Catholicism. The questions should be about how an orthodox Catholic judge’s religious commitments interact with his or her legal ones — which are exactly the questions the article itself raises. If it’s not anti-Catholic to have written the article, which it surely is not, it can’t be anti-Catholic to explore the implications of its arguments for other matters.

Mark Tushnet is the William Nelson Cromwell professor of law at Harvard Law School.

The Big Idea is Vox’s home for smart discussion of the most important issues and ideas in politics, science, and culture — typically by outside contributors. If you have an idea for a piece, pitch us at [email protected].

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png