After Cosby’s vacated conviction, is rape a crime?

Is rape a crime?

That’s the question at the center of Michelle Bowdler’s provocative 2020 book with that title — and in light of the news on June 30 that a conviction against Bill Cosby, accused by 60 women of sexual assault and rape, would be vacated on constitutional grounds, Bowdler’s question takes on a new urgency.

The National Sexual Violence Resource Center estimates that only a quarter of all rapes committed every year are reported. According to RAINN (Rape Abuse Incest National Network), of every 1,000 sexual assaults, 310 will be reported to the police, 50 will lead to arrests, 28 to conviction, and 25 to incarceration. Although studies estimate that between 2 and 10 percent of rape claims are false reports — roughly the same rate as other crimes — law enforcement officials are disproportionately likely to dismiss rape cases as unfounded.

“Are there other crimes where the first question asked is whether the victim is being truthful,” asks Bowdler in her book, “and where there is no ensuing investigation to determine if that conclusion can be backed up with facts?”

Cosby’s case is an unusual one. He was convicted of sexual assault in 2018 in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and sentenced to three to 10 years in state prison for assaulting Andrea Constand more than a decade earlier, in 2004. However, in 2005, Cosby had come to an informal agreement with then-Montgomery County District Attorney Bruce Castor, under which Castor assured Cosby that he would not pursue criminal charges against him. When deposed in a civil case Constand brought against him later that year, Cosby admitted to giving Quaaludes to women he wanted to have sex with. That deposition was later used as evidence against Cosby in his 2018 trial.

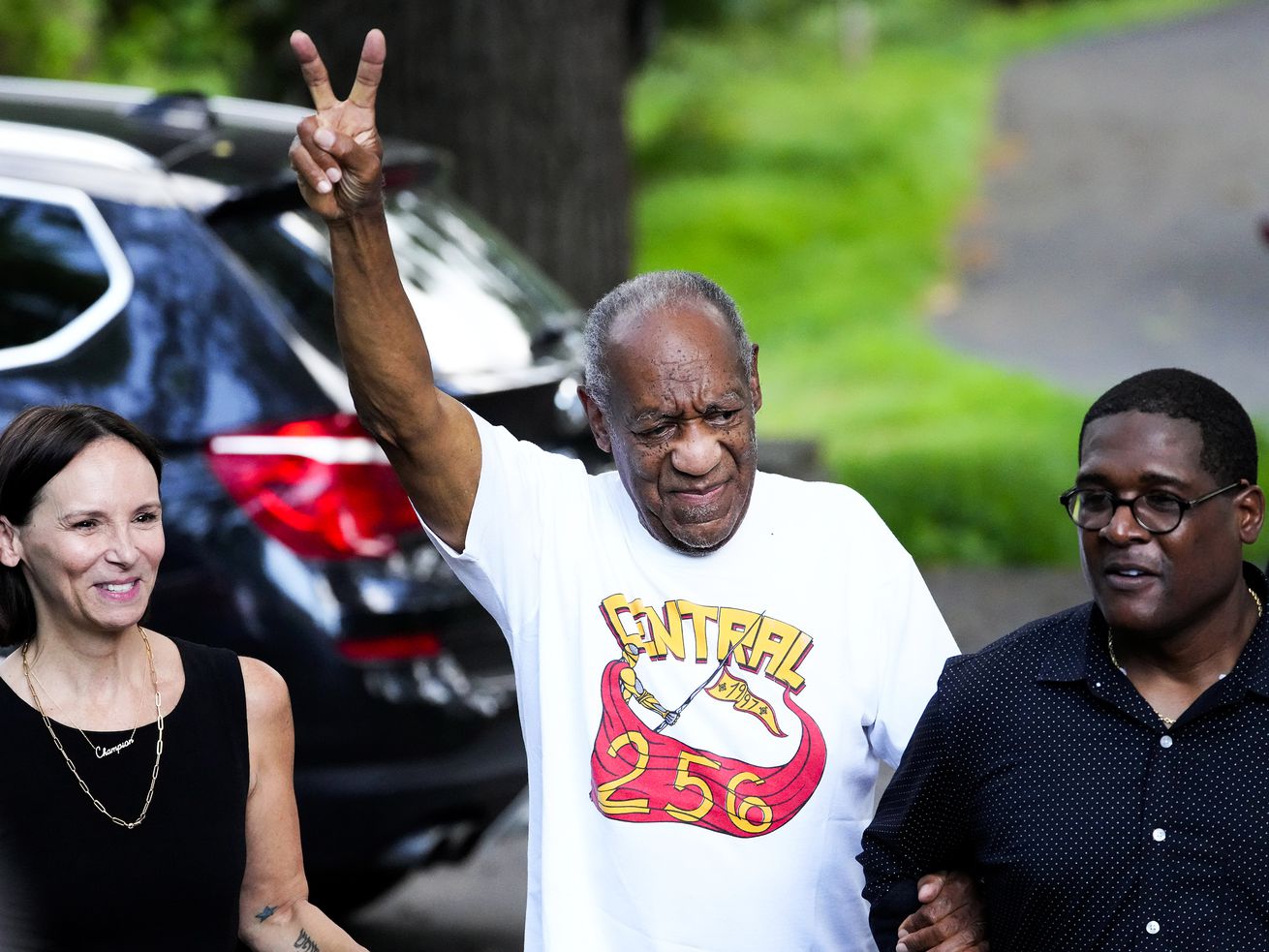

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22695658/GettyImages_1326349998_copy.jpg) Michael Abbott/Getty Images

Michael Abbott/Getty ImagesCosby most likely would not have made such an admission of guilt in his deposition if he had believed criminal charges would ever be brought against him, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court concluded. That logic formed the basis of its June 30 ruling that Cosby’s case would be vacated, and Cosby himself would be released from prison.

There’s a legal argument to be made that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court made the right call in a messy case, as Vox’s Ian Millhiser explains here. But within the context of a larger conversation about how painfully difficult it is to get a rape conviction, the vacation of a conviction as high-profile as Cosby’s is striking.

Is Rape a Crime? is one of the best summaries of that conversation I know of. Part memoir, part manifesto, it tells the story of how Bowdler navigated the aftermath of her own rape in 1984, when two strangers broke into her house and robbed and assaulted her at knifepoint. Bowdler reported her rape to the police immediately and submitted to a lengthy and traumatizing sexual assault evidence kit, but her attackers were never caught. It would be 20 years before she learned that the police never actually investigated her rape, apparently because the detective in charge of the case didn’t care for the department’s new bureaucratic policies on sexual assault cases and was throwing his weight around.

“My ability to learn about a life-altering trauma depended on what this person had done with my case,” Bowdler writes, “and, it seemed, he had done nothing.”

As Is Rape a Crime? makes clear, cases like Bowdler’s have happened all over the country: shocking acts of violence that the police would never investigate, or that prosecutors would decline to take to court, or that juries would dismiss out of hand; acts of violence that the apparatus of our law enforcement system would refuse, over and over again, to treat as crimes. That’s the context in which Cosby’s vacated conviction exists.

To make sense of it, I called up Bowdler, who is now executive director of health and wellness at Tufts University, and asked her to put it all into words for me. On the day after Cosby’s vacation was announced, we talked about how the justice system fails rape survivors, and what it would mean to truly treat rape as a crime. Our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, is below.

What does it mean to ask the question, “Is rape a crime?”

It actually was a question that was asked of me by a survivor. Initially, it shocked me.

She came to that question, and I came to that question, after doing advocacy work, trying to make changes with the criminal justice system, and feeling like we were not making the kind of progress that we would have expected given a lot of the conditions that existed. After yesterday, it felt even more relevant.

The question is actually meant to ask, “What does it take for survivors to feel like they can get any form of justice, or even acknowledgment of the devastation of this experience in our society?”

It is the least successfully prosecuted major felony. It’s the least reported. Out of the reported crimes, very, very few even go to prosecution and conviction. And while I have my own significant criticism of our current criminal justice system, it doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t at least look at why this felony crime is treated differently than all others.

I think some people would look at the case of what’s happening with Bill Cosby and say, “Okay, but his sentence isn’t getting vacated because law enforcement didn’t take his crime seriously. It’s because the prosecutorial team messed up.” How do you respond to that idea?

The prosecutorial team is part of the criminal justice system. Think about what it takes to get a conviction. Think of that New York magazine cover with 35 women, just sitting, who had accused him of the very same behavior. For a lot of different reasons, some came forward, and some didn’t feel comfortable prosecuting him. Which is understandable: He was rich and famous. Yet when they all came together, the pattern was created.

To have it vacated in that way, where he was reporting that he was vindicated, and he doesn’t have to register as a sex offender — it’s like none of what’s happened over the last several years has happened.

People were devastated. It just feels like more of the same. What does it take for people to be held accountable?

In 2017 and 2018, as the Me Too movement was really taking off, I think a lot of people hoped that something had fundamentally shifted in our culture, and that we were really starting to treat rape and sexual assault as serious crimes. Do you think that change really arrived?

Right after Harvey Weinstein, when people were losing their jobs who had been accused, it felt like a difference was starting. In fact, there was a blip in the data for 2017: The reporting of cases seemed to go from about a quarter to 40 percent. People wondered if that was going to be a trend. Now it’s back down to a quarter again.

Chris Matthews is back on TV. Jeffrey Toobin is back on TV. Charlie Rose might be making a comeback. Louis C.K. is sort of making a comeback.

It’s like, “I’ll say I’m sorry. I’ll say that I’m going to do some sort of treatment, and then I’ll come back.” It doesn’t really work that way, and the impact on victims and survivors doesn’t work that way either.

I do think people are talking about it and writing about it more. There is a lot more expression of outrage, and an awareness of how and why we need to make change. And that is appreciated.

But I think that we are going to have to do a lot more for the changes to stick: Overhaul our criminal justice system. Have more people in politics who look more like the rest of society. Have basic values of fairness and equity be expectable and not a surprise when they happen.

What would it look like to actually treat rape as a crime?

It’s about the response. Right now, somebody goes to law enforcement, and they’re not believed. It’s: “Are you sure about that? You’re a little fuzzy on details.” They’re trying to convince people not to go forward, because law enforcement is all about “what’s my win rate, what’s my case solve rate,” and rape cases are notoriously difficult.

So to begin with, to have the people who are hearing people’s stories treat it like any other report of a devastating event. Not wondering if it’s true as the first thing, but to just listen, care about it, and investigate it.

There were hundreds of thousands of rape kits in cities and towns all across the country that were never investigated. It was called a backlog, as though people intended to get to them but then they ran out of money. But in fact, many of these cases were closed without investigation.

This is a crime of violence. More than 50 percent of the people it’s done to think it will end with their death. It’s not he-said/she-said, yet people treat it as if it’s as likely that somebody’s lying as that they’re telling the truth.

We’re not going to get people reporting, and we’re not going to get people taken seriously, if we keep going on like this. But there’s healing that occurs when people just listen. If they believe you and say they’re sorry that it happened and they’ll try to investigate.

It’s really hard to go through a criminal case. So what if there was an alternative? What if we did more on restorative justice? What if we did more to shore up people who’ve experienced such a devastating crime, and had ways to have them feel like they could move forward in our world and function, as opposed to thinking about guilt and innocence and winning cases?

The whole model that we have is flawed. Our criminal justice system is not the model that I would look at to help rape victims feel taken seriously. But if we are going to, we have to have people trained in trauma response. We have to have a way for survivors to feel acknowledged and validated, and not treated like liars and as if they’re wasting people’s time. Which is too often the case.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More