For generations, forces worked to curtail Black freedom and joy. The Vineyard proved a safe place.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21899595/VOX_The_Highlight_Box_Logo_Horizontal.png)

Part of the Leisure Issue of The Highlight, our home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

The Inkwell, as one of Martha’s Vineyard’s famed beaches is known, stretches hardly 100 yards between jetties on the north shore of the island. To see it, it amounts to just a sliver of sand, but on a sunny day, the sea is vast and the precise color of jade, beckoning swimmers whose families have descended on the island in the summertime for generations.

Since the 1800s, Martha’s Vineyard (and the Inkwell) has been a renowned getaway for these Black families. The elite mingle with middle-class families on the island: Former President Barack Obama is rumored to have celebrated his birthday this month in his seven-bedroom mansion on Martha’s Vineyard. The island’s regulars over the years have included Henry Louis Gates Jr. and the late Vernon Jordan; Maya Angelou once described the town of Oak Bluffs, which includes Inkwell Beach, as “a safe place where we can go as we are and not be questioned.”

“I don’t have to catch my breath here,” says Skip Finley, an author and former broadcaster whose family has vacationed on the island for five generations. “It’s the freest place I’ve ever been.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786322/_DSC5447.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786241/_DSC5402.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786236/_DSC5364.jpg)

Vox sent photographer Philip Keith to Martha’s Vineyard, and to Oak Bluffs specifically, to capture the joy and community travelers find on the island today. The freedoms of Martha’s Vineyard highlight a truth about leisure in America: Lazy days in the sun, miles of coastline, and even the gut-churning and rickety climb up a monster roller coaster have not always been within the grasp of Black people.

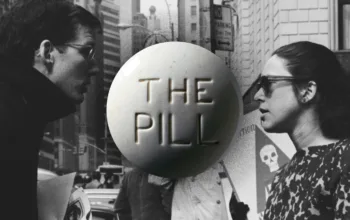

Through the first half of the 20th century, segregationists masquerading as public officials across the country drew literal lines in the sand, parceling less desirable beaches to people of color; shunning Black children from public pools; shuttering amusement parks to anyone but those with fair skin. Postal worker Victor H. Green penned The Negro Motorist Green-Book to guide African American travelers to safe, hospitable places, but the subtext was that the threat of violence could mar even the most benign of pursuits: For Black people in America, neither rest nor relaxation would come easily.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786292/_DSC5461.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786221/_DSC5536.jpg)

Among the safe spaces listed in The Green Book was Shearer Cottage, a Black-owned inn in the town of Oak Bluffs, on the north shore of Martha’s Vineyard.

Massachusetts was the first state to abolish slavery, and well-off African Americans had already built thriving lives and businesses in the state. “Martha’s Vineyard was part of the underground railroad, so it was known as a safe and welcoming community for African Americans,” says Nancy Gardella, executive director of Martha’s Vineyard Chamber of Commerce. “They didn’t feel entirely welcome in other beach enclaves.”

Along with the ferry that regularly deposited travelers right in Oak Bluffs, and the legions of Black families who began to visit beginning in the 1800s and then built dollhouse-like summer cottages in town, the inn helped spread word of Martha’s Vineyard’s comforts to families in Philadelphia; DC; Hartford, Connecticut; New York; and Boston.

Finley, who for years authored a column about Oak Bluffs, estimates that during the offseason, there are only 700 black people who call Martha’s Vineyard home, and, he says, “most of us are retired.” In the summer, the numbers swell markedly, till, he guesses, 30 to 35 percent of the summertime population is people of color.

“That doesn’t mean that bigotry and discrimination doesn’t exist. Whatever happens in the world happens on Martha’s Vineyard,” says Gardella. At the time of The Green Book, few inns on the island accepted Black travelers, and the image of Martha’s Vineyard in popular culture remains one of whiteness and privilege.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786297/_DSC5469__1_.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786389/_DSC5433.jpg)

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786331/_DSC5250__2_.jpg)

But the reality challenges any notions of the island as an exclusive place.

On Martha’s Vineyard, “I can be who I want, when I want. Which is not necessarily true of the rest of the country,” says Finley. “When we get on a boat or plane to leave here, we call it ‘going to America.’”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22786420/_DSC5441.jpg)

Philip Keith is a photographer born and raised in Boston. He graduated from the Boston Arts Academy. His last assignment for the Highlight was photographing economist Emily Oster.

Author: Vox Staff

Read More