Gunn’s dismissal from Marvel and its Guardians of the Galaxy franchise is only the tip of a much bigger, more hate-filled iceberg.

In early July, a video game writer named Jessica Price embarked on a lengthy Twitter thread about the storytelling differences between games meant to be played as single-player experiences and games meant to be played by lots and lots of people at once, like Guild Wars 2, the massively multiplayer online role-playing game Price was a writer for.

Price’s thread received a perhaps too-haughty response from gaming YouTuber Deroir, who disagreed with some of what Price had to say. Price — who is, after all, a woman on the internet and thus is subject to a stunning amount of social media pushback and condescension — put Deroir on blast, first tweeting: “Today in being a female game dev: ‘Allow me–a person who does not work with you–explain to you how you do your job,’” and later following up with: “like, the next rando asshat who attempts to explain the concept of branching dialogue to me–as if, you know, having worked in game narrative for a fucking DECADE, I have never heard of it–is getting instablocked. PSA.”

The Guild Wars 2 community erupted in outrage at Price, who had either stuck up for herself against the endless onslaught of needling criticism that comes with being a woman online or had abused a position of authority to call a popular member of the gaming community an asshat by implication. (Price’s tweet didn’t directly call Deroir an asshat, but it was hard to miss her meaning.)

A few days later, ArenaNet, the company that makes Guild Wars 2, fired Price and her co-worker Peter Fries, who had defended Price in several Twitter threads. Price told Polygon that she was not given a chance to explain herself, or to apologize. She was simply fired, as was Fries.

The broad outlines of the controversy drew comparisons to Gamergate, the controversial movement that began in 2014 and involved a bunch of gamer and alt-right trolls using the cover of concern for ethics in video gaming as an excuse to harass women in the industry and to claim that calls for better representation and diversity within gaming were destroying video games.

Was Price’s firing a result of Gamergate’s actions? Not directly, no. Deroir was not a Gamergate adherent, and he wasn’t agitating for Price to be removed. Plus, plenty of people who found Price to be in the wrong weren’t Gamergaters.

But the answer to that question also has to be yes, because of how thoroughly the matter was discussed in Gamergate’s favored corners of the internet, which mostly jumped to Deroir’s defense, and because of how completely Gamergate changed the way games are talked about online and how women in the industry have to think about what might happen to them, something Price touches on in her Polygon interview.

In the years since 2014, Gamergate has metastasized and evolved into what feels like the entire alt-right movement, to the degree that many of the names boosted by the hyped-up controversy, names like Milo Yiannopoulos and Mike Cernovich, saw their stars only rise when they became central to online communities that backed the presidential candidacy of one Donald Trump. Gamergate went from a fringe movement that struck most people who heard about it as a weirdo curiosity to something that took over the country, as Vox’s Ezra Klein predicted it would with eerie accuracy in late 2014.

Gamergate didn’t manage to completely eliminate more diverse storytelling in games, as at least one silly controversy from this year would indicate, but it did slightly paralyze the video game industry. And that paralysis has begun to spread to other spheres of our culture.

Members of the movement have developed a tactic that they have deployed again and again to drive dissension in assorted online communities, using a mix of asymmetric warfare (in which they stage lots and lots of small strikes at giant corporations that don’t quite know what to do in response), the general lack of accountability applied to the movement’s various decentralized figures, and a tendency to turn progressive concerns inside out, in a weird attempt to reach parity. Gamergate didn’t really have anything to do with Price’s firing directly, but it also did, because Gamergate is now everywhere and everything.

The movement arguably elected a president. And just this past week, in a much higher-profile case than the firing of Jessica Price, it got director James Gunn fired from Marvel’s Guardians of the Galaxy franchise.

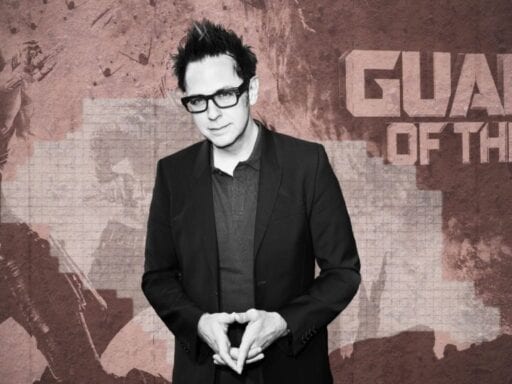

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/11736757/983983346.jpg.jpg) Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images for Disney

Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images for DisneyPerhaps the above mention of “Mike Cernovich” has already pinged some part of your brain that remembers keywords from the news and headlines of the past few days; it was Cernovich who helped engineer a push to have Gunn fired from the third Guardians of the Galaxy film, by dredging up and encouraging his followers to circulate several of Gunn’s old tweets. Many of the tweets contain jokes about topics like rape and pedophilia.

Gunn’s roots are in over-the-top shlock cinema (he began his career at the famed low-budget genre movie company Troma, and his first credit is for writing Tromeo and Juliet). He directed the first two Guardians movies to general acclaim, and both his overall positivity and his general disdain for Trump have earned him more than a few left-leaning fans on social media platforms.

But that same disdain for Trump — and, of all things, the widespread pushback against a tweet in which filmmaker Mark Duplass praised conservative writer Ben Shapiro, which inspired Gunn to chime in on the fray — made Gunn a target for folks like Cernovich.

To be clear, Gunn’s past jokes are awful. They have surfaced before — most notably in 2012, when Gunn was hired to helm the first Guardians film. A blog post he had written in 2011 about which comic book characters fans would most like to have sex with drew ire from numerous left-leaning critics and social media personalities. Gunn ultimately apologized for his comments, and vowed to do better.

Later, in 2017, he told BuzzFeed that in the early days of his tenure at Marvel, he’d abandoned the persona that aimed to be a provocateur and adopted the persona that evolved into his current Twitter self. As described by BuzzFeed’s Adam B. Vary:

“I protect myself by writing scenes where people shoot people in the face,” Gunn said, chuckling. “And if I have to think around shooting someone in the face, it’s harder, but I think it’s more rewarding for me.” He cleared his throat. “I felt like Guardians forced me into a much deeper way of thinking about, you know, my relationship to people, I suppose. I was a very nasty guy on Twitter. It was a lot fucking edgy, in-your-face, dirty stuff. I suddenly was working for Marvel and Disney, and that didn’t seem like something I could do anymore. I thought that that would be a hindrance on my life. But the truth was it was a big, huge opening for me. I realized, a lot of that stuff is a way that I push away people. When I was forced into being this” — he moved his hand over his chest — “I felt more fully myself.”

And what’s “this”?

”Sensitive, I guess?” he said. “Positive. I mean, I really do love people. And by not having jokes to make about whatever was that offensive topic of the week, that forced me into just being who I really was, which was a pretty positive person. It felt like a relief.”

Yet all those old tweets remained on Twitter. Considering both Gunn’s 2011 blog post and the way he talks about his old tweets, it seems hard to believe that neither Marvel Studios nor its parent company, Disney, knew of their existence.

But when Cernovich surfaced a whole bunch of them last week in a graphic designed to strip them of as much context as possible, more and more conservative and alt-right personalities started passing them around, and Disney’s Alan Horn finally announced on Friday that Gunn would no longer be working for the company. (Gunn, for his part, made one of the better, “Yeah, I fucked up!” statements in a decade that seems to provide a new one every other week.)

Then Cernovich and his friends turned their sights on other comedy figures with provocative jokes in their past, like Michael Ian Black, Patton Oswalt, and Dan Harmon. Few of these men suffered consequences as severe as Gunn did for past jokes. But all were hounded endlessly on social media. Harmon even left Twitter.

I don’t particularly want to defend Gunn here. A lot of his old Twitter material is truly awful. It often takes the shape of a joke without actually being funny, which is deadly to anybody playing with comedic land mines like gags about child molestation and rape. Meanwhile, it’s also hard to believe that a white dude who directed two of the biggest movies of all time won’t get another chance in Hollywood, even if he has to step back and spend a year or two making indie movies.

But the way Gunn was fired sticks in my craw, just a little bit. It’s the biggest example yet of Gamergate and its ilk forcing a major public figure out of the job that made them a major public figure. By stripping events like this of their context, Cernovich and company might think they’re forcing the left to confront its own hypocrisies, or winning smaller battles in a larger culture war, or simply driving critics of the president off social media.

But make no mistake, they’re also destabilizing reality.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/10558903/148094_9898.jpg) ABC

ABCThe recent event that Gunn’s dismissal has drawn the most comparison to is ABC’s firing of Roseanne Barr from the now-canceled TV show that bore her name. (The series will live on as a spinoff titled The Conners, sans Barr.)

In that case, too, an awful tweet (in this case, a racist remark about former Obama staffer Valerie Jarrett) led to somebody who seemed protected by recent success being removed from the franchise that had yielded said success. And in that case, too, the person fired had worked for the Walt Disney Company, the biggest behemoth in the entertainment industry, one that’s about to swallow another behemoth like it’s a tiny little goldfish.

But pull back some of the layers and the two events couldn’t be more dissimilar. The most obvious difference is the timing. Gunn wrote his tweets in the late 2000s and early 2010s, before he was hired by Marvel and long before he became a critic of Trump. Barr’s tweet was published the morning she was fired.

This is not to say that Gunn’s tweets are excusable but, instead, to point to all the instances in which Barr posted horrible tweets shortly before ABC picked up a new season of Roseanne, only for Disney and ABC officials to laugh them off. If Disney meant to establish a precedent with what happened with Barr, it was essentially, “If you have skeletons in your closet, whatever. Just don’t add any new ones.” Gunn, if nothing else, had seemed scrupulous about the “not adding any new ones” part (that we know of so far, at least).

An even bigger difference between Gunn’s and Barr’s tweets concerns the context of the tweets and the intention behind them. Most of us might judge Gunn’s tweets as bad jokes, sure, but they’re mostly recognizable as jokes, and jokes in the style of 2000s Gen-X comedians trying like hell to provoke a reaction by being as “edgy” and offensive as possible.

What’s been interesting, too, is watching many of the comedians in question — including Gunn and Black but also folks like Sarah Silverman, Sacha Baron Cohen, and South Park creators Trey Parker and Matt Stone — try to figure out how to navigate an era when the ironic offensiveness they trafficked in has been co-opted by a movement that insists they always meant it, deep down. Most have become vocal Trump critics. But few have managed the transition very easily.

This is the danger in making jokes rooted in ironic offensiveness, even when you’re a master of the form (like Silverman is). At a certain point, somebody is always laughing right alongside you and taking from the joke the message that racism is okay if it’s funny, or that provoking a reaction from someone by joking about rape is funnier than the joke itself.

Ironic offensiveness is far too easy to twist into the idea that nothing is worth caring about, and that getting those who do care to lash out is the funniest thing possible. That idea is now the basis of an entire internet culture that kept splintering, with one of those splinters becoming dedicated to trolling above all else. It eventually got to a point where nobody was sure who was serious and who was joking, or if there was even a difference.

Start to unpack the comedy of the figures listed above, or of their modern comedic descendants and fellow travelers like the terrifically funny hosts of the leftist podcast Chapo Trap House, and you’ll find that somewhere, deep down, they care deeply. The ironic offensiveness and shocking humor is meant to spur a reaction that hopefully guides you to a similar sense of caring and sincerity. But that requires genuine engagement and thought, and it’s easy to opt out of genuine engagement and thought when you’re laughing, in favor of taking the joke at face value.

This, I think, is what happened to Barr, who went from being an incisive comedian to being a millionaire many times over to being someone who promoted some of the same conspiracy theory nonsense that Cernovich peddles. (It’s no mistake that many of the tweets Cernovich surfaced to try to tank Michael Ian Black’s career involved him simply talking about pizza — in the worldview of Cernovich and Barr, there is a massive left-wing conspiracy to engage in pedophilia and protect fellow pedophiles, often using “pizza” as a code word for child sex.) Gunn didn’t really believe what he was saying; Barr did.

But does that context matter? Or does the statement itself matter? The fact is, both Barr and Gunn said horrible things. If we draw hard moral lines in the sand, if we insist that certain things matter to us and are important to uphold as ethical guidelines, does it ever matter that somebody might genuinely move past something bad they did in the past, might become a better person? Or are we all, always, defined by our darkest, worst moments?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/2455394/xbox.0.jpg) Shutterstock

ShutterstockA little over a week ago, the most popular Gamergate subreddit, Kotaku in Action, briefly went offline. The user who had created the subreddit in the first place, david-me, then posted to r/Drama (a subreddit dedicated to tracing internal Reddit action and excitement) saying that he had shut down KIA. Explaining his logic, he wrote, in part:

KiA is one of the many cancerous growths that have infiltrated reddit. The internet. The world. I did this. Now I am undoing it. This abomination should have always been aborted.

So in this moment with years of contemplation, I am Stopping it. I’m closing shop and I can’t allow anyone to exploit my handicap. I’ve watched and read every day. Every single day. The mods are good at what they do, but they are moderating over a sub that should not exist. The users have created content that should not be. Topics that do not require debate. And often times molded by outside forces.

We are better than this. I should have been better than this. Just look at the comment history of any users history. The hate is spread by very few, but very often. Overwhelmingly so.

Reddit and it’s Admins are Me. They are the stewards of hate and divisiveness and they let it go. They go so far as to even claim there is nothing they can do about it. Those with upvotes could have been stopped by others with equally powerful downvotes. Fallacy. 100 evil people with 100,000 upvotes can not be defeated by 100,000 with 100 downvotes.

Reddit stepped in. It restored Kotaku in Action, and by extension restored one of Gamergate’s most prominent platforms. The subreddit hadn’t directly violated Reddit’s hate speech rules, even if it was constantly dancing on the very edge of them. If Kotaku in Action is a cancer, as its founder alleges, then it is one that remains free to spread unchecked.

When I was covering the early days of Gamergate, I believed the core of its argument was, in essence, that caring is a waste of time — that wanting video games to have more diverse characters and the industry that makes them to have better representation across the board was a pointless exercise. Gamergate adherents seemed to believe the focus of the industry should be making better games, an argument that ignored that for many, having more diverse games was necessary for having better games.

I was wrong. The core argument of Gamergate, and of the alt-right more generally, has always been that caring is hypocritical. Deep down, both movements believe that everybody is racist and sexist and homophobic, that the left, especially, is simply trying to lord a moral superiority over everybody else when, in secret cabals, they kidnap babies and run child molestation rings out of the basements of pizza restaurants. This idea is referred to as “virtue signaling,” meaning that there is no such thing as real virtue, only a pretend virtue that people deploy to try to win points with mainstream society, when everybody would be better off dropping the pretense and letting their most offensive freak flags fly.

And it’s tricky to combat the idea of virtue signaling, because of course we all virtue-signal all the time. Parents virtue-signal to teach their children, and corporations virtue-signal to make their products seem more palatable to a rapidly diversifying America, and I virtue-signal every time I tweet something that says I’m supportive of, say, the Black Lives Matter movement without joining affiliated protests.

But that doesn’t mean I don’t want the broader goals of BLM to be realized immediately, or that corporations won’t take your money regardless of color or creed, or that parents shouldn’t teach their children not to resort to violence when others say or do something they don’t like.

Virtue signaling is still virtue, even if in your heart, you’re so angry or upset that you feel like punching someone. Cynicism about the motivations behind good acts doesn’t erase that the acts are good. We all do all sorts of things for a variety of complicated reasons. It doesn’t erase the fact that the net result of those actions ultimately has very little to do with our motivations.

The argument of Cernovich and his cronies is, ultimately, that none of us is actually good, that we are all venal and horrible, and that we live in a world where we should all, always, be pitted against each other, defined only by our worst selves. And because nobody is ever going to fire Cernovich for all the times he’s tweeted about rape, because he’s a self-made media personality, the war becomes ever more asymmetric. The only people who can hold Gamergate and its adherents accountable are members of the movement, who will occasionally toss someone out but almost always do so under the pretense of a game or, worse, a joke.

There are real people whose lives are ruined, each and every day, by Cernovich and his ilk, and our modern corporate media climate continues to have no idea what to do about it, because the battles are deliberately constructed to strip away context and to predetermine their outcomes from the first.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/3625770/twitter.0.jpg) Andrew Burton/Getty

Andrew Burton/GettyI began this article with the story of Jessica Price instead of the story of James Gunn for a reason. It’s entirely possible you haven’t heard of either, but if you’ve only heard of one, it’s almost certainly James Gunn. Yet the devastation to Price’s career will be much more substantial than whatever happens to Gunn, who will at least be collecting residuals from the Guardians movies for the rest of time.

Price’s situation is a valuable lesson in how so much of this works because the circumstances of her firing are muddier and harder to prosecute. Yes, the representative of a corporation that sells a service probably shouldn’t be calling her customers asshats. But any woman with a large enough social media profile knows just how quickly a seemingly innocuous, “Actually…” can turn into a massive dogpile of Twitter yahoos with nothing better to do. What happened to Price ostensibly has nothing to do with Gamergate. But its shadow lurks nonetheless, because it is now everywhere.

Could Price have handled things better? Probably. Should she have been fired for how she did handle them? I find that a lot harder to argue. It suggests that every employee of every organization with a vaguely public-facing persona has to be 100 percent perfect all of the time across all platforms, or else. And if you remove enough context from just about anything, you can make somebody look as bad as you want, unless they’re anodyne and milquetoast all of the time, which leads to sitting US senators suggesting that perhaps James Gunn should be investigated for pedophilia “if the tweets are true.”

The idea, I guess, is that we should all just turn off the internet and step away from social media when things get too hairy. But I would hope we all realize how impossible that is most of the time, and it’s in that imbalance that Cernovich and his pals forever create dissension and uncertainty.

I said above that what Cernovich wants to do is destabilize reality; that might seem like a big leap, but think about it. We’ve already gone from “these are bad jokes” to “if the tweets are true,” from carefully examining the thing in context to quickly glancing at the thing with as little context as possible, so that it looks as bad as it could possibly be. And when you’re fighting a culture war, and grasping for requital, I suppose that’s fair. Culture wars, too, have their victims.

But this still leaves us with a world where the terms of the game are set by a bunch of people who argue not in good faith, but in a way designed to force everybody into the same bad-faith basket. They are interested not in finding a deeper truth but in the easy cynicism of believing that everybody is as dark-hearted and frightened as them, that the world is a place that can never be made better, so why even try? Flood the zone with enough bad information and turn reality into enough of a game and you can make anything you want seem believable, until bad jokes become a dark harbinger of a horrific reality looming just over the horizon.

I’ve never believed that approach can win in the long run. I’ve always believed that in the end, some sort of truth will hold fast, and the fever will break. But sometimes, of late, I wonder if I’m wrong — and the only thing that stops me from convincing myself is the fear that accepting even guarded optimism as futile would only turn me into one of them, forever spiraling and never reaching bottom.

Author: Todd VanDerWerff

Read More