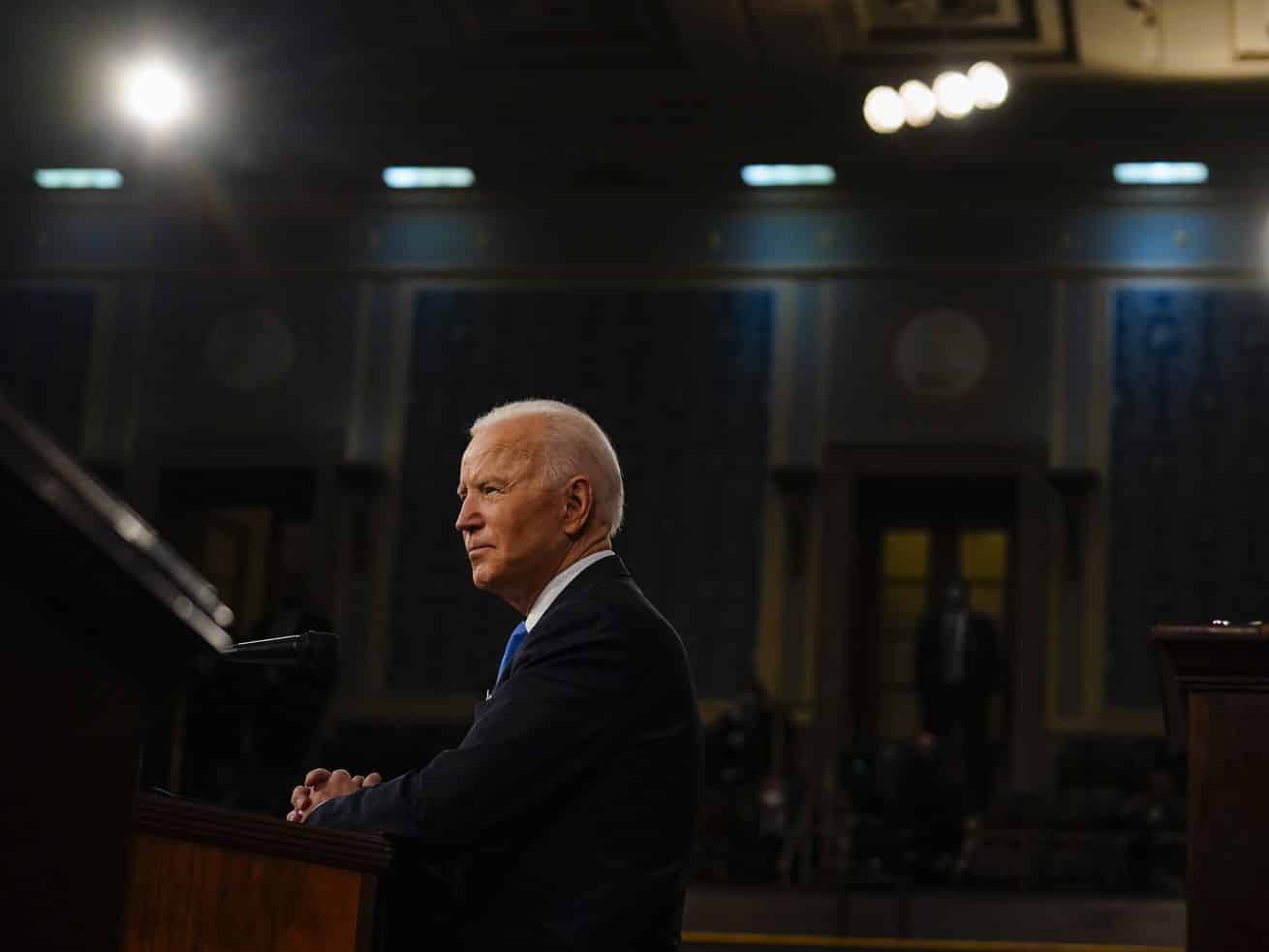

In his speech to Congress, Biden echoed FDR with a call to do big things and restore faith in America.

Even before President Joe Biden was elected, three letters came to stand in for the scope of his presidential ambition: FDR.

Like Franklin Delano Roosevelt at the start of the Great Depression, Biden took office at a time of crisis, and has tried to use that crisis to reshape government. Biden’s team invited the comparisons to FDR, too — just about any sitting Democratic president wants his agenda compared to one of the most successful political projects in US history.

But FDR didn’t merely seek to pull America out of the Great Depression. With the rise of fascism around the world and crumbling trust in government at home, a rising chorus of elite voices questioned if American democracy was even working.

FDR wanted to prove that it did. That was the “deal” part of the “New Deal”: a new contract between the government and the public, including the marginalized. It was supposed to be proof that a democratically elected government could be responsive to the “forgotten man” and build a better country for all.

Biden doesn’t face the global rise of fascism. But his plans aim to address the same challenge: not just “building back better” after the coronavirus, as his slogan has it, but showing that a democracy can still build, period.

Abroad, Biden faces the rise of an autocratic China — he recently told news anchors that Chinese President Xi Jinping is “betting [that] democracy cannot keep up with him.” At home, he faces the legacy of President Donald Trump and the Republican Party, who have pandered to white nationalists, sought to make it harder to vote, rejected election results, and ultimately inspired supporters to storm the Capitol on January 6.

“We have to prove democracy still works,” Biden said at his speech to a joint session of Congress on Wednesday night. “That our government still works — and we can deliver for our people. In our first 100 days together, we have acted to restore the people’s faith in democracy to deliver.”

He then made the parallel even clearer: “In another era when our democracy was tested, Franklin Roosevelt reminded us — in America, we do our part.”

He touted his biggest legislative achievement so far — a $1.9 trillion relief package — and his largest proposals — a $2 trillion infrastructure and jobs plan and $1.8 trillion investment in families — as a means to directly help people, but also to bolster the idea of America at home and around the world.

“For Roosevelt, there was an explicitly political purpose to the public works programs — to restore Americans’ belief that the government works for them,” historian Eric Rauchway, author of Why the New Deal Matters, told me. “Biden’s rhetoric about restoring confidence in America, that’s a parallel to Roosevelt’s intentions.”

What Biden is really seeking to build with his policy agenda, in other words, isn’t just bridges, roads, and child care, but the supports that prop up a modern democratic welfare state: the public’s faith in government itself.

No one knows if Biden’s efforts will work. Maybe American distrust in government is too entrenched, after plummeting and remaining low since Watergate and the failures of the Vietnam War. Maybe political polarization is simply too powerful at this point, as Americans divide into identities of red and blue. And given those trends, maybe Biden won’t be able to complete enough of his agenda — particularly his massive proposals for jobs and families — to prove anything at all.

“Things have been in such a bad state, frankly, that no one wants to be overconfident about what will make a difference,” Suzanne Mettler, a political scientist at Cornell, told me.

But the stakes Biden faces are high, between avoiding anything like a repeat of the Capitol riots at home and keeping up with China abroad.

Biden wants to prove the government can work

From the start, Biden’s legislative priorities have been geared toward addressing problems that directly affect Americans’ day-to-day lives.

The first is, obviously, Covid-19. When Biden came into office, Trump, who through Operation Warp Speed presided over the vaccines’ quick development, had botched the initial rollout of the vaccines — sending doses to the states, but giving little to no guidance and support for how to actually distribute them.

When Biden promised to change course, he offered not just a new plan but a different vision of the federal role. The Trump administration had rejected more federal aid — one of Trump’s top advisers even described more support to states as a federal “invasion.” Biden’s plan embraced a bigger role for the federal government, arguing it could get the job done. So far, it has: The US went from around 2 million people fully vaccinated before Biden took office to nearly 100 million today.

The other big problem Biden faced was the tanking economy, which he sought to combat with a $1.9 trillion Covid-19 relief package. Trump pushed for $2,000 checks to Americans, but he could only get $600 checks done due to his own party’s resistance to a bigger sum. Biden’s package included the $1,400 checks for Americans, netting the rest of the $2,000. It also included policies that aim to cut America’s uninsured rate by subsidizing health care, reduce child poverty with America’s first real child allowance, and still help the unemployed make ends meet with a $300-a-week-boost to jobless benefits. All of that was on top of the $2.2 trillion and $900 billion stimulus bills Congress had already passed under Trump.

The next phase of Biden’s agenda, is his two “Build Back Better” proposals. That includes traditional aspects of infrastructure programs, including building roads and bridges but also renewable energy projects. But it also includes other aspects of infrastructure — under an expansive definition of the term — that reaches into what experts have called the “care economy,” including paid leave and child care, and education, from universal preschool to free community college. It’s an attempt to address the parts of the economy that have failed so many Americans in the past year of the pandemic, as many were forced to decide between their careers and education or taking care of their kids and other family members.

This third phase is the closest parallel to the New Deal. With his American Jobs Plan and American Families Plan, Biden is promising to build up necessary infrastructure and create potentially millions of jobs. That alone will directly help a lot of people — anyone who has to drive on a shoddy bridge during their daily commute, but also people who struggle to afford child care or health insurance, have to take time off work to take care of a family member, or want to get their kids into a high-quality preschool program. But in doing all of this, he’s also demonstrating the broader point that the federal government can do all of this.

The New Deal, similarly, had a lot of programs directly geared to the economic recovery, including public works and other infrastructure projects that helped employ millions of Americans. But as FDR’s agenda gained support, he leveraged that trust placed in him to tackle longstanding progressive priorities. While old-age poverty wasn’t the biggest driver of the mass suffering of the Great Depression, it was a longstanding problem nonetheless in the US, so FDR used the moment to enact Social Security. In doing so, FDR reinforced that America couldn’t only act in a crisis but also solve truly big problems.

“There’s a global crisis of democracy in 1933,” Rauchway said. “This is when Hitler comes to power. There’s a broad sense that democratic institutions have failed. For Roosevelt and the Democrats, the New Deal is a way to challenge a lack of faith in democracy.”

Biden’s agenda is also a departure from recent administrations in one crucial respect: It’s an embrace of big government. One of Biden’s predecessors, former President Bill Clinton, famously claimed in 1996 that “the era of big government is over” — and Democrats for decades governed accordingly, afraid of anything giving the appearance of government overreach. Even President Barack Obama, who passed the ambitious Affordable Care Act, ultimately succumbed to the austerity politics of his time to downsize his own stimulus package and set spending caps.

The bet that Biden is making is that Democrats’ abandonment of the FDR legacy is precisely what gave rise to Trumpism: By failing to address expanding economic inequality, the collapse of manufacturing hubs, the slow recovery after the Great Recession, and the opioid epidemic, the federal government enabled the public discord and rage that enabled Trump. By acting more boldly now, the thinking goes, Biden can help reverse these trends.

With the rise of fascism lurking in the background, FDR wanted to prove to Americans that the government could work for them. With Trump; a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia; the Capitol riots in the background; and the rise of autocratic China, Biden is trying to do the same.

“I predict to you, your children or grandchildren are going to be doing their doctoral thesis on the issue of who succeeded: autocracy or democracy?” Biden said at a press conference in March, speaking about China. “Because that is what is at stake.”

We don’t know if Biden’s policy efforts will work

It’s fine to talk about being the next FDR, but Biden will now have to prove he can do it — and do much more than he has so far. The economic relief package he passed helped a lot of people, but it’s not that different in size and scope from the stimulus legislation passed under Trump. Where Biden is now promising something more transformative — the kind of measures comparable to the New Deal — is in his “Build Back Better” proposals. If enacted by Congress, both plans could reshape American life with permanent programs that would tackle climate change, clean energy, child care, preschool, and higher education, and more.

“I don’t want to be a downer,” Rauchway said. “But if this doesn’t happen, things aren’t nearly as comparable to the New Deal as they would be if it does.”

That depends on whether a Democratic-controlled Congress can actually enact Biden’s proposals. If Congress fails, it could signal to the public that, contrary to Biden’s vision, the American government — with its many veto points and incentives for both major political parties to grind basic governance to a halt — really can’t tackle larger problems. The failure could prove a sort of doom loop for public trust in US governance.

When FDR took office, he did so with huge Democratic majorities — more than 60 percent of the Senate and more than 70 percent of the House — and less polarized political parties. Biden’s party holds a slim majority in the House and a tie broken by his vice president in the Senate. Support and opposition during FDR’s time could flow between party lines — some of his biggest critics were Southern Democrats. But the most conservative Democrat in the Senate has largely embraced Biden’s agenda. And Biden’s real challenge is the fact that the vast majority of Republicans don’t like him, with Biden getting only an 11 percent approval rating among members of the GOP, according to Gallup’s polls.

The hyperpartisanship helps explain why Americans can be so initially disapproving of their presidents today. In the past, newly elected presidents like Harry Truman, Richard Nixon, and Jimmy Carter could receive approval ratings above 60, 70, or even 80 percent. More recently, presidents like Ronald Reagan, George W. Bush, and Obama could hit the high 50s and 60s. During his first 100 days — typically a honeymoon period for presidents — Biden hasn’t been able surpass the mid-50s, according to FiveThirtyEight’s tracker. That’s a lot of resistance baked into his presidency, and likely anything he does, from the start.

It’s also possible that American views on the role of government are now too entrenched. Since Watergate and the Vietnam War, the American public’s trust in government has by and large dwindled. In 1975, 52 percent said they had a great deal and quite a lot of trust in the presidency, according to Gallup’s surveys — and this was after Watergate, which almost certainly hurt confidence. In 2020, that was down to 39 percent. That reflects decades of built-in attitudes, the kind of damage that one president alone will struggle a lot to reverse.

Nor will it be so easy to reverse longstanding trends, from economic inequality to drug overdoses, that likely reinforced that distrust in the first place. “We have a perfect storm for people to not trust government,” Julia Azari, a political scientist at Marquette University, told me. “I don’t know Biden can fix that, certainly not in 100 days.”

Even if Biden’s agenda does pass, the next phase would be actually selling these programs to Americans. During the New Deal, FDR made it a point to emphasize what the government was doing for them — hence the slogan “Built for the People of the United States” plastered all over Tennessee Valley Authority projects. If Biden’s goal is to show that the government is working for the people, that’s going to take some, well, showing.

All of that is to say is what Biden does in his next 100 days — really, next 1,300 — matters a lot too.

When FDR accepted the Democratic nomination for president, he laid out a “simple moral principle” that “the welfare and the soundness of a nation depend first upon what the great mass of the people wish and need, and second, whether or not they are getting it.” He went on to pursue an agenda that made sure Americans were getting it.

Biden’s presidency is built on the idea that Americans, 90 years later, can still believe in that principle. To prevent another Trump, beat China, and boost democracy at home and abroad, he’s depending on it.

Author: German Lopez

Read More