It starts reckoning with the Obama administration’s legacy, but stops short of some big progressive reforms

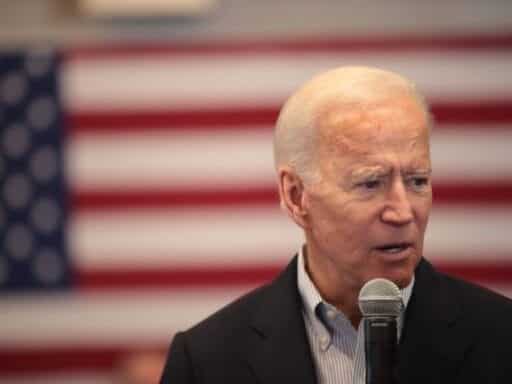

Joe Biden released an immigration plan on Wednesday that focuses on undoing President Donald Trump’s policies while acknowledging critiques of his Obama-era record on the issue.

Biden, a frontrunner in the Democratic primary, has positioned himself as former President Barack Obama’s natural successor. His plan touts his record as vice president, including his support of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), Obama’s plan to give temporary protection to unauthorized immigrants brought to the US as children.

Biden has struggled to answer questions in several recent debates about Obama’s more controversial policies on immigration enforcement, which included record-high levels of deportations and were often criticized by activists.

But in his plan, Biden begins to outline ways to make the existing immigration enforcement system more humane.

“Joe Biden understands the pain felt by every family across the U.S. that has had a loved one removed from the country, including under the Obama-Biden Administration, and he believes we must do better to uphold our laws humanely and preserve the dignity of immigrant families, refugees, and asylum-seekers,” his campaign said.

Biden is one of the last candidates to release an immigration plan. (The only candidate participating in the December debates who has yet to release one is Pete Buttigieg, the mayor of South Bend, Indiana.)

He doesn’t back some of the more progressive policies that have been proposed or embraced by other candidates: decriminalizing the act of crossing the border without authorization, placing a temporary moratorium on deportations, or redesigning the agencies in charge of immigration enforcement.

But it’s significant that Biden has chosen to highlight the fear and insecurity in immigrant communities that started with the deportations that occurred under the Bush administration, became more widespread under Obama and has escalated under Trump. It suggests that he would not simply revert to the status quo on immigration enforcement under Obama — even if his immigration plan attempts to revive some of the former president’s policies.

The Biden campaign did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

What Biden’s plan would do

Biden promises to end President Donald Trump’s practices of keeping immigrants in detention long-term, separating families and conducting large-scale immigration raids that aim to arrest unauthorized immigrants already living and working in the US — proposals in line with those from the rest of the Democratic field.

He also vows to end a slew of Trump’s toughest anti-immigrant policies: the “public charge” rule making it more difficult for low-income immigrants to enter and settle in the US; his travel ban on individuals from seven countries he deems to be national security threats; and restrictions on asylum including the Migrant Protection Protocols, under which Trump has sent tens of thousands of migrants back to Mexico to wait for their court hearings in the US.

Biden proposes reforms to the legal immigration system, including a plan to create a new visa category that would allow cities counties to apply for higher levels of immigrants.

He would renew the US’s focus on protecting vulnerable immigrant populations, including asylum seekers and refugees. He would immediately increase the number of refugees the US admits to 125,000 annually, on par with what Sen. Elizabeth Warren has promised (and more than Obama admitted), staff up immigration courts and shore up protections for domestic violence victims and those fleeing political persecution.

To address the root causes of migration in Central America, he would invest $4 billion over four years to combat corruption, attract private sector investment, develop civil society and incentivize countries to conduct their own reforms. (Though, that’s still less than the $1.5 billion in annual aid to Central America that Warren has proposed.)

Biden says he would work with Congress on comprehensive immigration reform, which isn’t likely to pass so long as Republicans control the Senate. The closest Congress has come to a compromise on comprehensive immigration reform in a generation was the bipartisan “Gang of Eight” bill that passed the Senate 68-32 in 2013.

The bill would have reinvented the immigration system, notably creating a 13-year path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants and a new visa for low-skilled workers, requiring employers to verify the employment authorization of their workers, and shifting away from policies emphasizing family ties in favor of work skills. But it was ultimately doomed after House Republicans refused to hold a vote on the bill under pressure from grassroots anti-immigrant voters.

To get comprehensive immigration reform done in 2020 would require an unlikely series of events: Democrats would have to flip the Senate and hold the House, and the next president would have to make it an immediate legislative priority. That’s why many lawmakers have abandoned the idea of “comprehensive” reform, instead opting for a piecemeal approach on issues like visas for agricultural workers that can attract bipartisan support.

One noted absence from Biden’s plan: Most of his opponents have embraced the idea, originally proposed by Julián Castro, of decriminalizing the act of crossing the border without authorization by repealing section 1325 of the Immigration and Nationality Act — one of the legal provisions that allowed the Trump administration to separate thousands of immigrant families in 2018.

Under that proposal, immigrants would never be “charged with a crime, immediately deported or detained for more time than strictly necessary for crossing the border,” as Dara Lind explained for Vox.

Though discussions of decriminalization featured heavily in the early Democratic debates, polls have shown that about 67 percent of voters aren’t in favor of it.

Biden doesn’t embrace that proposal, saying instead that he would end criminal prosecutions that separate families and punish people for lawfully requesting asylum and would end blanket prosecutions that undermine due process and the rule of law.

He would also focus on deporting only immigrants who pose a threat to national security and public safety — a designation that relies largely on the discretion of individual immigration officers.

The Obama administration’s “Secure Communities” program, meant to deport primarily people with records of violent crime, proved that it’s difficult to draw the line between who constitutes a threat and who doesn’t. Under that program, which ended in 2014, it wasn’t just violent criminals who were deported, but also individuals with minor infractions such as traffic tickets.

It’s not clear how Biden would guarantee that his administration wouldn’t repeat the mistakes of that program, but he says he will ensure “individuals are treated with the due process to which they are entitled and their human rights are protected.”

Biden calls for investing in programs that do not require immigrants to remain in detention long-term, including releasing immigrants on the condition that they wear ankle monitors, and support migrants in ensuring that they show up for their immigration appointments.

The Obama administration started investing in these programs — which have been shown to be effective and much cheaper than detention — toward the end of his presidency.

For those who are detained, Biden vows to improve their living conditions, promising improved accountability for immigration agencies like US Customs and Border Protection and US Immigration and Customs Enforcement. (The plan isn’t specific about what this accountability would look like.) And he calls for ending for-profit detention centers, which have been sites of some of the most egregious abuses of immigrants in recent years.

He also calls for ensuring that US Immigration and Customs Enforcement isn’t allowed to arrest immigrants at “sensitive locations” including hospitals, schools, and workplaces — but he does not mention courthouses among such locations. ICE has stepped up courthouse arrests of unauthorized immigrants under Trump, despite the fact that federal judges have prohibited the practice in some areas of the country on the basis that it discourages them from showing up for their hearings.

Reckoning with Obama’s immigration record

Biden has closely tied his candidacy to his time as Obama’s vice president. His plan even repeatedly mentions Obama’s accomplishments, including the former president’s efforts to offer legal status to certain unauthorized immigrants and pass comprehensive immigration reform.

But Biden has also struggled to answer persistent criticism of immigration enforcement tactics under Obama, particularly in the first four years of his presidency.

Advocates labeled Obama the “deporter in chief” for deporting more immigrants than any other president — over 3 million between 2009 and 2016 and peaking at 409,849 in fiscal year 2012.

When a migrant crisis hit in 2014, when over 60,000 unaccompanied children from Central America showed up at the southern border, the Obama administration was caught unprepared. Border officials detained children in jail-like facilities for longer than the 72 hours that is permitted by law. The administration set up temporary housing similar to the soft-sided facilities Trump has constructed and tried to detain migrant families for extended periods of time.

Eventually, courts stepped in to put an end to these practices. And in his second term, after comprehensive immigration reform failed in Congress, Obama also shifted toward more sweeping executive actions, including creating the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program and issuing an executive order instructing ICE to deport “felons, not families.”

Still, part of Obama’s record has proved a burden to Biden. His most senior Latina staffer even resigned recently over her frustration with Biden’s rhetoric about Obama-era immigration policy.

In November, Biden snapped at an immigration activist who asked him at a South Carolina town hall whether he would support a moratorium on deportations. He said that he would prioritize deportations only of those who have committed a felony or a serious crime, telling the activist to “vote for Trump” if that wasn’t good enough.

When asked about the deportations that occurred under Obama during a debate in September, Biden did not budge: “I stand with Barack Obama all eight years, good, bad and indifferent.”

He stumbled on the same question about whether he regretted Obama’s deportations at a Democratic debate in July, saying that he was vice president at the time and that he does not speak about his private recommendations to the president.

On the whole, however, Obama’s record on the whole is likely boosting Biden more than it brings him down: The former president remains popular among Democratic voters, and left-wing criticisms of his immigration policies rarely attracted major political backlash while he was in office.

The activist community still thinks Biden could be bolder in his approach to immigration. Biden isn’t trying to tear down the existing immigration enforcement system — he’s just trying to administer it more humanely. For immigrant advocacy groups like Movimiento Cosecha that believe that the underlying system needs to be entirely reinvented, that’s not enough.

“Here’s what Biden fails to see, or is willfully ignoring: Our laws themselves are inhumane & deny the dignity of immigrants,” the group tweeted Wednesday.

Author: Nicole Narea

Read More