He needs nine more.

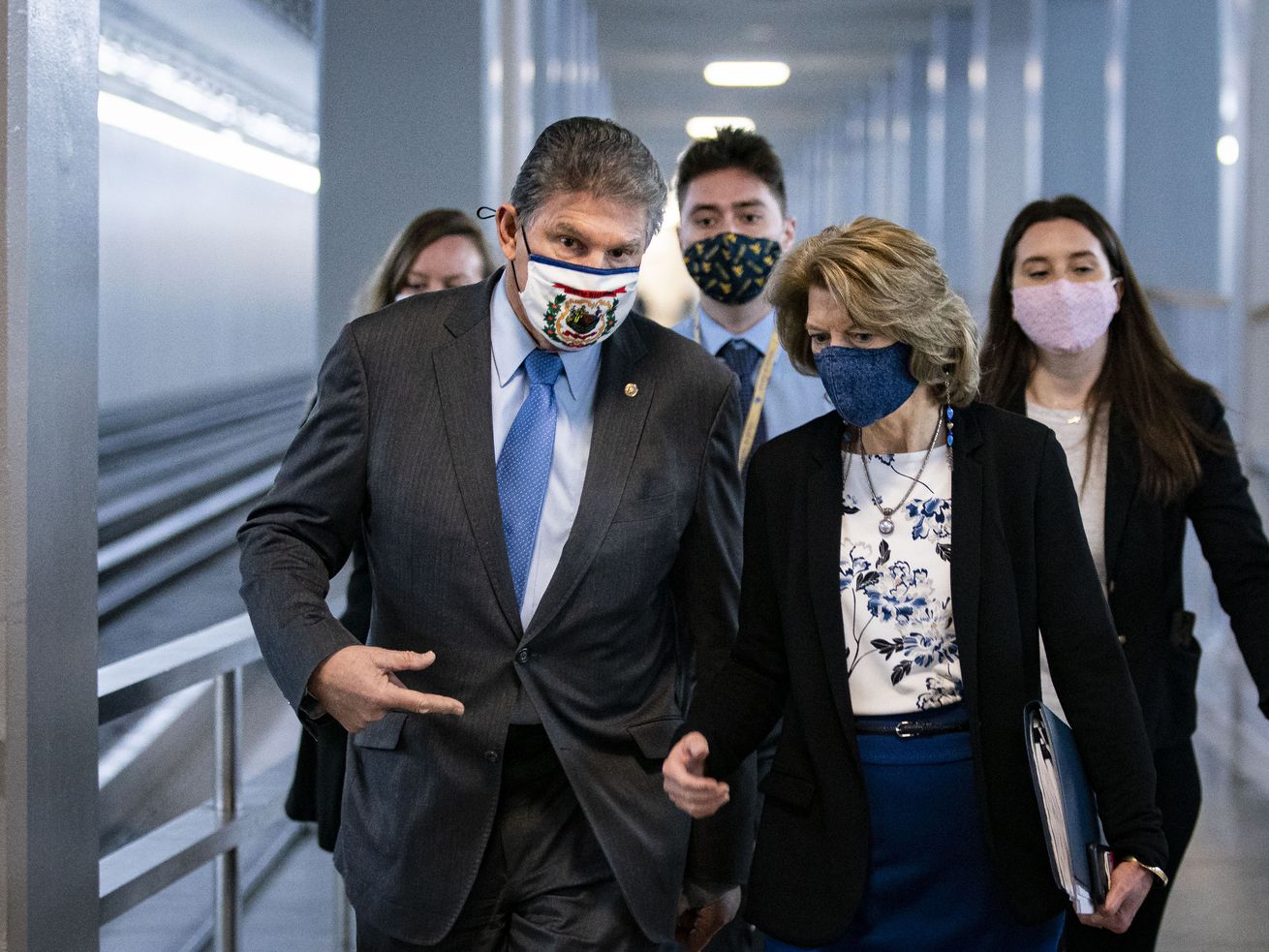

Sen. Joe Manchin (D-WV) announced that he’s found a Republican partner willing to work with him to restore the Voting Rights Act. Manchin and Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) released a letter to congressional leaders on Monday stating that “Congress must come together” to pass a “bipartisan reauthorization of the Voting Rights Act through regular order.”

Murkowski is not a newcomer to this fight. In the previous Congress, she was the only Republican senator to co-sponsor the Voting Rights Advancement Act, a bill backed by nearly all Senate Democrats that seeks to restore preclearance in some states. (Manchin was one of the few Democrats who did not co-sponsor the bill).

The open question is whether Murkowski alone will be enough. Manchin has repeatedly suggested that any voting rights reform should be bipartisan. He’s even signaled that he may oppose his party’s primary voting rights proposal — a comprehensive bill known as the For the People Act — because the bill does not enjoy any Republican support. Instead, Manchin floated a surprisingly bold proposal to protect voting rights last week.

Before the Supreme Court struck down much of the Voting Rights Act in 2013, states with a history of racist voting rules were required to “preclear” any new election rules with officials in Washington, DC. Manchin proposed restoring this preclearance regime, and he also suggested that all 50 states should be required to submit their election laws to federal review before those laws could take effect.

Manchin has thus far resisted amending the Senate’s filibuster rules to allow voting rights legislation to pass without at least 10 Republicans agreeing to support it. If he holds to that position — and the Manchin/Murkowski letter’s call to pass a bill through “regular order” suggests that he hasn’t changed his position on the filibuster yet — the bill is almost certainly doomed.

But, at the very least, he can now claim that his voting rights push has bipartisan support. The question is whether Manchin will eventually decide that a bill supported by only one or a few Republicans should become law.

3 questions facing Congress if it wants to restore the Voting Rights Act

As originally enacted, the Voting Rights Act requires states with a history of racist election practices to submit any new voting rules to the Justice Department or to a federal court in Washington, DC. Such a rule would not take effect unless either DOJ or the appropriate court determined that it neither had the “purpose” or the “effect of denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race or color.”

Prior to the Court’s decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which effectively neutralized this preclearance regime, nine states were subject to preclearance on a statewide basis: Alabama, Alaska, Arizona, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia.

Before Congress could restore preclearance, it would have to resolve three questions. The first is which states would be subject to preclearance immediately after a Voting Rights Act restoration bill became law.

Manchin suggested that all 50 states could be subject to preclearance — a proposal that would be much more expansive than the original Voting Rights Act. The primary Democratic proposal, by contrast, would only impose preclearance on state and local governments where “15 or more voting rights violations occurred in the State during the previous 25 calendar years,” or on jurisdictions with 10 or more violations, “at least one of which was committed by the State itself.”

It’s not immediately clear which states would be subject to preclearance under the current version of this Democratic proposal — the answer would depend on when the bill became law. And, in any event, more conservative members of Congress might seek to reduce the number of states that were impacted by the bill if it were actually passed on a bipartisan basis.

Second, members of Congress would also need to resolve how easy it would be to add new jurisdictions to the list of state and local governments that are subject to preclearance. Under current law, new jurisdictions can theoretically be added to the list, but only if a voting rights plaintiff can show that the state acted with racist intent when it enacted a new election rule.

The primary Democratic proposal would make it possible to expand preclearance to new states or localities without necessarily requiring plaintiffs to prove discriminatory intent. Manchin’s 50-state proposal, meanwhile, would obviate the need to figure out how to expand the scope of preclearance because all 50 states would be required to submit their election rules to federal review.

Finally, Congress needs to decide whether to make a Voting Rights Act restoration bill retroactive. The original Voting Rights Act became law in August of 1965, but it provided that states under scrutiny must preclear any new election rule enacted after November 1, 1964. So it effectively required the covered states to preclear some rules that were already in effect when the bill became law.

Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp (R) signed a fairly comprehensive voter suppression law on March 25, 2021, and this is the first of several such laws that are likely to pass GOP-controlled state legislatures in the coming months. So, if Congress does reinstate preclearance, Democrats will most likely want to make the new law retroactive to at least March 24, 2021, to capture the latest round of Republican voter suppression laws. But it’s not clear whether Democrats could pass a voting rights bill that applies retroactively.

There’s still a long road ahead before a new voting rights bill could become law. And it remains to be seen whether a bipartisan deal can be struck that includes Republicans other than Murkowski — maybe Republicans would be willing to agree to Voting Rights Act restoration if Democrats offer to pass a nationwide voter ID bill?

For the moment, however, Murkowski appears to be the only Senate Republican who is interested in moving forward on voting rights. Unless that changes, voter protections are likely to hinge on whether Manchin is willing to budge on filibuster reform.

Author: Ian Millhiser

Read More