The civil rights icon was told to cut a too-radical line from a famous speech. It says a lot about who he was.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

Part of Issue #10 of The Highlight, our home for ambitious stories that explain our world.

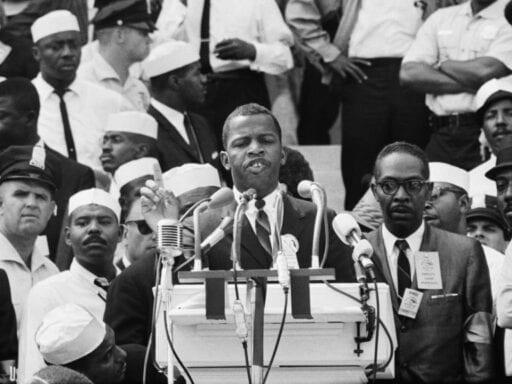

In 1963, John Lewis was, at 23, the youngest person set to speak at the March on Washington. The original version of his prepared remarks accused the Kennedy administration of conspiring with white supremacists. He wanted to ask: “Which side is the federal government on?”

But the march’s leaders censored the speech he wanted to give, arguing that it was too radical. The event leaders forced Lewis to take out that question, and tone down other provocations, including this call to action:

We will march through the South, through the heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own scorched earth policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground — nonviolently. We shall fragment the South into a thousand pieces and put them back together in the image of democracy.

They made him change that to: “We will march through the South … with the spirit of love and with the spirit of dignity we have shown here today.” But the words Lewis didn’t speak are the ones America needs to hear right now.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19598266/GettyImages_469385493.jpg) Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty Images

Afro American Newspapers/Gado/Getty ImagesMore than 50 years later, history has clarified some things. The quintessential American battle between racial justice and white supremacy is still unresolved, but we know which side the Trump administration is on. And nobody thinks love and dignity are going to change a damn thing. Well, nobody except Cory Booker, and he just dropped out of the presidential race.

Lewis is now the long-serving Democratic Congress member from Atlanta. His recent announcement that he is fighting stage 4 pancreatic cancer has inspired admiring appraisals of his integrity and service to the nation. Known as the “conscience of the Congress,” Lewis has influenced almost every major rights movement of the past century, from voting rights to LGBTQ equality.

Lewis’s prognosis also calls for a reckoning, not of his life, which is unquestionably heroic, but of the movement he symbolizes. Lewis was one of the original Freedom Riders. He is the only person who spoke at the March on Washington who is still alive.

Perhaps the civil rights movement’s central accomplishment was to stigmatize racism. The moral force of Martin Luther King Jr.’s message shamed the nation, especially during the Cold War era, when the United States purported to be a beacon of human rights. Now, virtually no one wants to be called a racist; even white supremacists take pains to explain how they are not biased against black people.

Beyond the symbolic, the movement deserves huge credit for the Voting Rights Act, widely considered the most successful civil rights law in US history. Violent protests helped garner support for the legislation, in particular Bloody Sunday, the 1965 protests in which the police used nightsticks, whips, horses and tear gas to terrorize a group of civil rights activists. The group was marching across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, demonstrating for the right to vote. A cop hit Lewis so hard, it fractured his skull.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19598282/GettyImages_515494150.jpg) Bettmann Archive

Bettmann ArchiveLess than three weeks later, President Lyndon B. Johnson introduced the Voting Rights Act, and Congress passed it the same year. The removal of discriminatory restrictions such as poll taxes and literacy tests allowed black people in the South meaningful access to the vote for the first time since Reconstruction.

In just two years, the percentage of African Americans registered to vote in the jurisdictions the act covered increased from less than one-third to more than 50 percent. Black voter participation allowed meaningful access to democracy. The year the law was enacted, there were six African American members of Congress. After the 2018 election, there were 52.

The blood of John Lewis, and the blood of other American heroes, helped accomplish this landmark achievement.

On the day Barack Obama was inaugurated as the first African American president, he inscribed a photo to Lewis with the words, “Because of you, John.” Here was possibly the most successful African American in US history paying homage to a man who was the son of sharecroppers, but whose activism — and more than 45 arrests — had made that success possible.

Yet sometimes I feel like the angry black man the good congressman has refused to be, because of what has not changed. In 2020, a large percentage of black, Latino, and white children attend segregated schools. Black families have a median net worth of $17,061, compared with $171,000 for white families. Getting killed by the police is a leading cause of death for young black men.

The Voting Rights Act? In a case decided in 2013, the Supreme Court gutted it, striking down the section that required oversight of all the places that had tried to deny folks the right to vote on account of race.

The civil rights movement was far from a failure, but if the goal was to meaningfully remove barriers to anti-black discrimination, it has not been a success.

Fifty years later, looking back at his March on Washington speech, Lewis said removing the more radical lines from his speech was “the right thing to do.” He told an interviewer that he had “always tried to be a team player” and that when civil rights icons King, A. Philip Randolph, and Roy Wilkins approached him and asked him to delete some of the most radical content, he couldn’t say no.

But as a country, would we be better off if we had heard — and heeded — these words that Lewis wanted to speak in August 1963?

The revolution is at hand, and we must free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery. The nonviolent revolution is saying, “We will not wait for the courts to act, for we have been waiting for hundreds of years. We will not wait for the President, the Justice Department, nor Congress, but we will take matters into our own hands and create a source of power, outside of any national structure, that could and would assure us a victory.

The question is whether people of color can “free ourselves of the chains of political and economic slavery” within the existing legal structure of the United States. Or was the poet Audre Lorde correct when she wrote that “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house”?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19598312/GettyImages_465533764.jpg) Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images

Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty ImagesI don’t know. But I hope President Obama was right. In 2015, on the 50th anniversary of Bloody Sunday, he traveled to Selma and marched across the Edmund Pettus Bridge arm-in-arm with Lewis. Obama said:

What greater expression of faith in the American experiment than this; what greater form of patriotism is there; than the belief that America is not yet finished, that we are strong enough to be self-critical, that each successive generation can look upon our imperfections and decide that it is in our power to remake this nation to more closely align with our highest ideals?

The civil rights movement was a good start, but it wasn’t enough.

Well done, Congressman Lewis. Hopefully with your blessing, a new generation will take it from here.

Paul Butler is the Albert Brick professor in law at Georgetown University and an MSNBC legal analyst. A former federal prosecutor, he is the author of Chokehold: Policing Black Men.

Author: Paul Butler

Read More