In 2017, over the Martin Luther King Jr. holiday weekend, President-elect Donald Trump started a Twitter war with civil rights hero and Congress member John Lewis. “All talk, talk, talk – no action or results,” Trump wrote of Lewis, after Lewis said that he did not consider Trump to be a legitimate president. “Sad!”

But Lewis achieved monumental results over his career, both in government and as a civil rights protester. To prove it, you don’t have to look any further than his books.

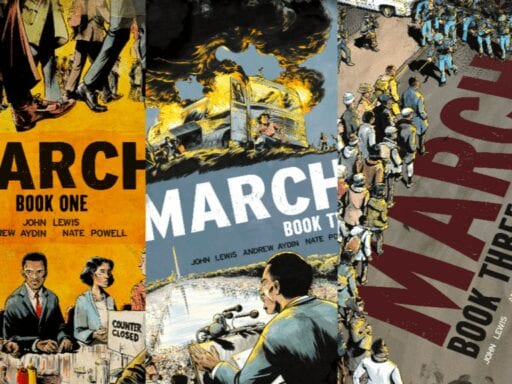

March is a series of graphic memoirs written by Lewis and his staffer Andrew Aydin, illustrated by the award-winning graphic artist Nate Powell. Books one and two were released in 2013 and 2015, and the third volume came out this August.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6690689/Screen%20Shot%202016-06-22%20at%202.23.50%20PM.png)

March chronicles Lewis’s long history in the civil rights movement, detailing how he became one of its so-called Big Six leaders. But it starts early. In book one, set in the 1950s, we meet young Lewis, the son of share-croppers, dreaming of preaching the social gospel like Martin Luther King and practicing baptisms on his parents’ chickens.

Lewis went to college in Nashville, where he began to attend Jim Lawson’s workshops on nonviolent protest. In March, the workshops look harrowing: Participants alternate screaming racial slurs and threats at one another, their shadowy faces dominating the panels of each page as spittle flies from their mouths. “We tried to dehumanize each other,” says the caption. “We needed to see how each of us would react under stress.”

But the workshops also used gentler tactics. Participants studied a comic book called Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, which outlines King’s strategy of nonviolent action as a tool for desegregation. It was his experience with this comic, Lewis says, that led him to agree to write his own story as a graphic novel when Aydin approached him with the idea — and he hopes that March, like The Montgomery Story, will teach a new generation about the power of nonviolent protest.

On every page of every volume, March insists on nonviolence in the face of violence and oppression. It is unflinching in its depiction of the rage and brutality of the racist opposition Lewis encounters; the second volume features a particularly memorable scene where a little blond boy grins and curls his fingers like claws while an adult voice booms from above, “That’s my boy. Git him! Them eyes — git them eyes!”

Over the course of his career, Lewis has been beaten bloody, hospitalized, and arrested multiple times, culminating in 1965’s infamous Bloody Sunday, when Lewis attempted to lead protesters across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in a march from Selma to Montgomery, only to be viciously attacked by state troopers and police officers. Through it all, Lewis remained stoic and unresponsive, refusing to react to violence with violence.

This summer’s gun control sit-in on the floor of the House recalls a much earlier part of Lewis’s career: the sit-ins in Nashville that form the climax of March’s first volume.

In 1960, Lewis’s Nashville Student Movement was in the process of executing a series of “test sit-ins” — asking segregated lunch counters for service, then politely leaving once it was established that the lunch counter would not fulfill that request — when the famous Greensboro Woolworth’s sit-in took place. Four black students sat down at a Woolworth’s in North Carolina and refused to get up until they were served. The sit-in made national headlines.

Lewis decided his group had done enough testing. A week after the Greensboro sit-ins began, the Nashville Student Movement started holding their own.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6696755/March-interior-p93-sit-in.jpg) Top Shelf Productions

Top Shelf ProductionsNashville’s white community did not respond peacefully.

“Violence does beget violence,” declares one of March’s captions, as a group of young white men attempt to physically wrest Lewis and his fellow demonstrators off their stools, “but the opposite is just as true. Fury spends itself pretty quickly when there’s no fury facing it. The beating subsided.”

Over the course of the Nashville Student Movement’s sit-ins as portrayed in March, Lewis and his fellow protestors were beaten, drenched with condiments, sprayed with fire hoses, and even gassed with insecticides. They were arrested multiple times. The NAACP disavowed them as a group of young radicals.

But they persevered, and they succeeded. Segregation became illegal. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed.

If Trump wants to see someone with action and results, he doesn’t have to look any closer than John Lewis.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More