2020 is here, and the Democratic primary field is starting to winnow.

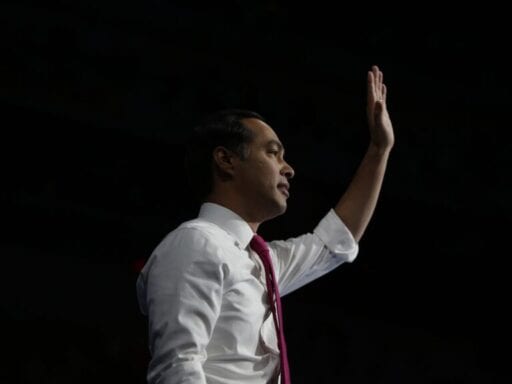

Julián Castro, former San Antonio mayor and President Obama’s secretary of Housing and Urban Development, has ended his bid for president.

“Today it’s with a heavy heart, and profound gratitude, that I will suspend my campaign for president,” Castro said in a video his campaign released Thursday.

“I’m not done fighting,” the field’s only Latino candidate continued. “I’ll keep working towards a nation where everyone counts, a nation where everyone can get a good job, good health care and a decent place to live. … Ganaremos un día.”

Castro made optimism and inclusion central to his campaign, working to ensure all his policy proposals put “people first.” And in a conversation with Vox’s Ezra Klein, Castro said that he wanted to push Americans to “expand the notion of we,” meaning to extend their ideas on who and what Americans are — and can be.

It’s with profound gratitude to all of our supporters that I suspend my campaign for president today.

I’m so proud of everything we’ve accomplished together. I’m going to keep fighting for an America where everyone counts—I hope you’ll join me in that fight. pic.twitter.com/jXQLJa3AdC

— Julián Castro (@JulianCastro) January 2, 2020

His plans placed a particular focus on empowering communities of color — he was the first candidate to create a plan to address policing, he wrote a proposal to clean up lead contamination, and he created a sweeping plan to increase Native Americans’ political power. He also advocated for a number of other issues few of his rivals have, including animal rights, protecting the homeless, and ending hunger in the US.

Castro’s signature policy, however, was one of his first: a comprehensive immigration proposal that advocated for repealing Section 1325, the part of United States Code that makes “illegal entry” — entering the US without papers — a civil offense instead of a federal crime.

He told Vox’s Nicole Narea he has championed this policy because “I’m not going to criminalize desperation.”

“We need to understand that these are human beings,” Castro said. “They’re not a criminal record or an invader or an other. They’re human beings that are simply coming — like generations have before — in search of a better life.”

Despite these ideas, Castro never became known as the candidate with bold policy proposals — that mantle fell on the shoulders of Sen. Elizabeth Warren; or Sen. Bernie Sanders, who wants to give power to the powerless. Both of those candidates eclipsed Castro in the polls.

He made it onto the debate stage at all of the early Democratic presidential debates — and was sometimes praised for his performances there — but in a crowded field, began to struggle both financially and in the polls ahead of the fifth and sixth debates in November and December, which he did not qualify for.

Castro threatened to end his presidential bid once before, in October, announcing he needed $800,000 before the end of the month in order to stay in the race. He met that goal, but was ultimately unable to sustain that momentum, leading to his decision to retire once and for all.

Julián Castro led the field on immigration policy

Castro released plans on a span of issues, but would often return to the issue of immigration, as he did in his discussion with Klein:

We’re trying to expand the notion of we. But we’re also looking inward and pointing out that [immigrants] have been a part of it the whole time. They’ve been a part of creating the nation and the identity of who “we” are. Perhaps we just haven’t given them credit for that or recognized them — even though they have been helping to propel this community forward. Now it’s time to recognize them as well as everybody else.

As part of this expansion, Castro worked to account for those immigrants who have not yet arrived in the US, including by creating a plan that would allow refugees to seek asylum for reasons related to climate change, and by pushing the issue of illegal entry to the forefront of the Democratic Party’s discussions on its immigration platform.

In fact, during the first Democratic primary debate, the former candidate did so literally, bringing up the issue of Section 1325 of Title 8 of the United States, which makes entering the US without proper documents a misdemeanor.

Castro has called for Section 1325 to be repealed, and by the end of that first debate, nearly every candidate in the field at the time — including the current frontrunners — said they agreed with him.

As Vox’s Dara Lind noted, getting rid of Section 1325 in the manner Castro suggested — making illegal entry a civil offense instead of a federal crime — would have a huge impact on the scale of immigration-related prosecutions, given that “in fiscal year 2016, immigration offenses — illegal entry and reentry chief among them — made up a majority of federal criminal prosecutions.”

And its repeal would mean the end of family separations, Lind explained:

Criminal prosecution of illegal entry was what gave the Trump administration the power to separate thousands of families in 2018. It referred thousands of parents for criminal prosecution for illegal entry — advertised as a “zero tolerance” approach — and thus separated them from their children to send them to criminal custody.

As this policy proposal Castro championed has been taken up by those candidates who are still in the race, it could very well become actual policy should the eventual Democratic nominee take the White House. With his dropout this week, that will have to be Castro’s campaign legacy.

Author: Sean Collins

Read More