It’s more robust than you might think.

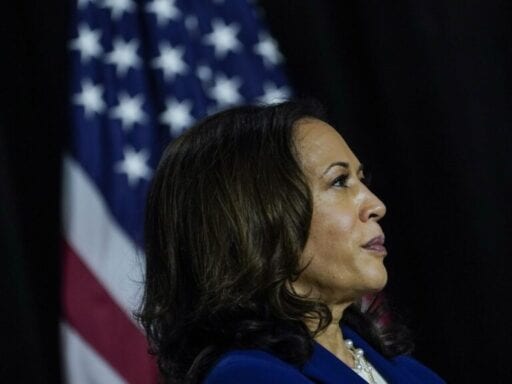

When it comes to foreign policy, Sen. Kamala Harris is very much the “simpatico” running mate Joe Biden was looking for.

Based on her Senate record, answers to questionnaires when she was a presidential candidate, debate remarks, and interviews with those who know her, many of Harris’s foreign policy views fall right in line with Biden’s.

She views America’s alliances and partnerships as crucial to solving global problems such as the coronavirus pandemic and climate change. She would prioritize diplomacy, human rights, and the promotion of democratic values like the rule of law — meaning that, among other things, she would push China to stop persecuting Uighur Muslims and cracking down on free speech in Hong Kong. And she’d focus on rebuilding economic strength and easing social tensions in the US so that the country could present a stronger, more united front abroad.

Harris, then, would staunchly bolster Biden’s global vision while in the White House. “In general, she is an internationalist,” said Halie Soifer, Harris’s national security adviser in the Senate from January 2017 to May 2018. “She would be a champion for rebuilding those alliances, partnerships, and America’s credibility in the world.”

The question some have is whether Harris would aim to exert as much power over foreign policy as previous vice presidents, such as Dick Cheney — or Biden himself. Most people I spoke to don’t believe so. “I don’t see her as much of a foreign policy leader,” Justin Logan, a US foreign policy expert at the Catholic University of America, told me.

“She obviously has very limited experience in the field,” Emma Ashford, a research fellow in defense and foreign policy at the CATO Institute, said.

But she could still make a splash as Biden’s No. 2: Harris is a critic of autocratic regimes, namely Russia and Saudi Arabia, and would certainly continue her rebukes. She remains a firm backer of Israel, to the chagrin of many progressive activists, and may reject calls to weaken America’s relationship with the country.

As a member of the Senate Intelligence Committee, Harris gained an appreciation for defending against foreign election interference and the dangers of cyberspace. Yet she’s been open about wanting to cut defense spending — usually an unpopular stance in US politics, and one that President Donald Trump has already seized upon as a means of attacking her.

“She wants to slash funds for our military at a level that nobody has — can even believe,” Trump said during a press conference Tuesday.

Foreign policy in a Biden administration would undoubtedly be led primarily by Biden himself, yet Harris still has the potential to be an impactful vice president on the world stage.

“Democrats certainly have confidence in Harris’s abilities to give her more space on foreign policy issues,” said Zachary Hosford, who worked with the senator’s office on global issues as an adviser to Sen. Edward Markey (D-MA). “I certainly would have confidence in her abilities there.”

Biden and Harris share similar worldviews

Biden has spent decades working on foreign policy, and many believe he’d be loath to relinquish control of that area to Harris. Indeed, that she’s not known for her global vision may be one reason he chose her as his running mate.

“I’d say that Joe Biden didn’t pick her for foreign policy credentials. He already has that angle covered,” said CATO’s Ashford. “She’s as likely to be steered by his foreign policy views as the other way around.”

That may be true, but it helps that both candidates on the Democratic ticket share remarkably similar foreign policy views. Here are the three main ones.

Alliances

Since the end of World War II, Democrats and Republicans have pursued largely similar approaches to US foreign policy. Presidents from both parties have used America’s power to underwrite and maintain what’s called the “liberal international order,” which basically means the set of economic and political rules and values that help the world function.

The US never did this out of the goodness of its heart. Promoting free trade and liberal democracy was meant to provide America with markets to sell goods to and countries with which to build alliances against adversaries. It was never a perfect system, and the US made many, many errors along the way. But overall, that grand strategy helped the US maintain its position as the world’s preeminent power.

That, in a nutshell, is the world Biden and Harris want to restore and protect.

“For the past seven decades, the choices we have made — particularly the United States and our allies in Europe — have steered our world down a clear path,” Biden said in a speech at the World Economic Forum annual meeting in January 2017, just two days before leaving office as vice president. “In recent years it has become evident that the consensus upholding this system is facing increasing pressures, from within and from without. It’s imperative that we act urgently to defend the liberal international order.”

Compare that with an answer Harris gave to the Council on Foreign Relations while she was running for president: “The greatest US foreign policy accomplishment has been the post-war community of international institutions, laws, and democratic nations we helped to build.”

Harris believes America keeping its commitments to allies helps bolster the nation’s power. “Part of the strength of who we are as a nation — and therefore, an extension of our ability to be secure — is not only that we have a vibrant military, but that when we walk in any room around the globe, we are respected because we keep to our word, we are consistent, we speak truth, and we are loyal,” Harris said during a Democratic presidential debate in November 2019.

Those views are key to understanding how Harris sees the world, those who know her told me. “She understands the importance of partnerships and alliances when it comes to our national security,” Rebecca Bill Chavez, a top member of Harris’s presidential campaign foreign policy team, said.

Human rights

Those close to Biden told me he’ll make human rights an important aspect of his foreign policy. Whether it’s reprimanding Saudi Arabia for the murder of dissident journalist Jamal Khashoggi or pushing China to end the internment of Uighur Muslims in Xinjiang, Biden plans to spend ample time on those and similar issues.

Harris would be fully on board with that agenda, people who worked with her said. “The issue of human rights is incredibly important to her,” said Soifer, the senator’s former national security adviser.

She’s already made defending human rights a significant part of her work in the Senate.

In June 2019, Harris voted to block arms sales to Riyadh to punish Saudi Arabia for Khashoggi’s murder as well as for the war it leads in Yemen, which has seen thousands killed and millions displaced. Harris also voted to end US support for that war earlier the same year — a war Biden has also vowed to pull America out of.

Saudi Arabia must be held accountable for Jamal Khashoggi’s murder and for its human rights abuses in Yemen. The last thing we should do is sell them billions in weapons.

That’s why this week I voted to block the sale of weapons to Saudi Arabia.

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) June 22, 2019

In the Council on Foreign Relations questionnaire, she also floated the idea of downgrading US-Saudi ties. “[W]e need to fundamentally reevaluate our relationship with Saudi Arabia, using our leverage to stand up for American values and interests,” Harris answered, though she acknowledged that there are areas — such as counterterrorism — on which the two nations could still cooperate.

Harris has also been very outspoken about China’s human rights abuses. She and 55 other senators co-sponsored the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019, which would end the special relationship between the US and the city Beijing aims to take over completely. And she joined 65 of her colleagues as a co-sponsor on the Uyghur Human Rights Policy Act of 2020, which President Donald Trump signed into law in June.

The law imposes sanctions on foreign individuals and entities involved in abuses in Xinjiang; it also requires the president to “periodically report to Congress a list identifying foreign individuals and entities responsible for such human rights abuses.”

It’s clear that China has no intention of respecting Hong Kong’s autonomy and fundamental right to exist as a democracy. The United States cannot stay silent while this egregious attack on democracy continues.

We must stand firm with the people of Hong Kong. https://t.co/fAfZQIudBX

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) May 23, 2020

Whether Harris maintains her staunch human rights defense while making complicated foreign policy deals with tough global leaders will be one of the more challenging dynamics of her time in office.

Climate change

Biden has promised that, as president, he would have the US rejoin the Paris climate agreement from which Trump withdrew. During her presidential campaign, Harris pledged the same. She also said she’d make climate change a central focus of America’s relationships abroad.

“Governments around the world should be bringing dangerous coal-fired power plants offline, not bringing new plants online, and underscoring that necessity should be front and center in every one of our bilateral relationships,” she told the Council on Foreign Relations. “We should also play a leadership role in compelling international institutions to use their leverage to end subsidies for dirty fuel.”

As a senator from California — a heavily Democratic state that has experienced extreme wildfires and flooded rivers, among other effects connected to climate change — it’s no surprise that Harris has made this a big priority.

In her 2019 book The Truths We Hold: An American Journey, she spent considerable time detailing the risks climate change poses to the world:

[C]limate change will lead to droughts. Droughts will lead to famine. Famine will drive desperate people to leave their homes in search of sustenance. Massive flows of displaced people will lead to refugee crises. Refugee crisis will lead to tension and instability across borders. …

The hard truth is that climate change is going to cause terrible instability and desperation, and that will put American national security at risk.

More wildfires.

Stronger hurricanes.

Rising sea levels.

Flooded rivers.Let’s be clear– climate change is here and we must act now.

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) October 18, 2019

We’re not talking nearly enough about what climate change will mean for our health. Children, older adults, pregnant women, people with chronic illnesses and allergies all face risk of greater health complications if we don’t act. Climate change is a public health emergency.

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) October 12, 2019

Put together, Harris will be in lockstep with Biden on some of his major foreign policy stances.

But Harris could also use her time in office to focus on some additional areas of particular interest to her — and potentially garner both positive and negative attention for doing so.

Where Harris might make a foreign policy name for herself

Many experts say Harris could carve out a role for herself — somewhat independent of Biden, but still with his blessing — on three key foreign policy areas.

Election interference and technology

As a freshman senator, Harris got the rare opportunity to serve on the Senate Intelligence Committee, where she delved deeply into the myriad national security threats facing the US.

Intelligence Committee members “are privy to some of the most clear threats the US has,” a person familiar with her views told me, speaking on condition of anonymity because they were not authorized to speak on behalf of the Biden campaign. One of the main threats Harris focused was Russian election interference, the former aide said.

It’s something she speaks about often. “When they influenced our elections, they diminished in some ways the integrity of our election system, and therefore their goal was accomplished,” Harris said at the Lesbians Who Tech & Allies virtual Pride Summit in June. “And they did it through technology.” Mandating paper ballots on Election Day, Harris has proposed, is one way to help strengthen the security of US elections.

California is home to Silicon Valley, and many of Harris’s most powerful constituents are intensely focused on securing their technologies against attacks from Russia, as well as from China, North Korea, and Iran.

She’s clearly soaked up a lot of their concerns. “Cyber warfare is silent warfare,” she wrote in her 2019 book. “I sometimes refer to it as a war without blood: There are no soldiers in the field, no bullets and bombs. But the reality is cyber warfare aims to weaponize infrastructure and, at its worst, could result in casualties.”

As a younger, more tech-savvy politician than Biden, it’s possible Harris could take a bigger role in safeguarding America’s electoral system and US-made technologies.

Defense spending

Back in June, Sen. Bernie Sanders proposed a 10 percent cut to the national defense budget — which is currently over $700 billion — to pay for other priorities, including health care, education, and investment in new jobs. It was a controversial amendment to a defense bill that failed multiple times in Congress, and Harris voted against the measure.

Yet she made clear she backed the general thinking behind it. “I unequivocally agree with the goal of reducing the defense budget and redirecting funding to communities in need, but it must be done strategically,” Harris said in a statement on her decision to oppose the amendment. “I remain supportive of the effort, and am hopeful that with the benefit of additional time, future efforts will more specifically address these complicated issues and earn my enthusiastic support.”

Harris’s hesitance to vote for such a large cut makes sense: California has the largest population of military members and their families in the US — a fact she explicitly noted in her statement — and such a constituency certainly cares about the size of the US defense budget.

However, Harris did vote against another increase to the budget in July, and has long said some of the money the military usually gets could go to diplomats and investments in other parts of the federal budget, such as technological innovation, education, and environmental protection.

Cutting the defense budget will certainly meet stiff resistance from most Republicans and some Democrats, should Biden and Harris both agree it’s a good idea (those close to Biden told me he’d likely push to cut the defense budget). Harris could use her relationships from her time in the Senate to lobby allies to vote for a cut, which would place her squarely in the center of a major initiative of the Biden administration.

Israel

Progressive Democrats in recent years have called for a reevaluation of America’s decades-long close relationship with Israel, concerned about the rightward shift in Israeli politics under Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his government’s policies toward the Palestinians.

Many progressives weren’t happy to see Biden become the likely nominee — and they’re not likely to be any happier with Harris as his running mate.

Simply put, she’s been unequivocal about standing by Israel.

Her first foreign policy vote in January 2017 was to criticize the UN for condemning the country on its settlements in Palestinian territories. Later that year, she spoke at the annual conference of the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC), a US lobbying group that advocates for a strong US-Israel relationship. “I believe the bonds between the United States and Israel are unbreakable. And we can never let anyone drive a wedge between us,” she said.

“[The] first resolution I cosponsored as a United States senator was to combat anti-Israel bias at the United Nations and reaffirm that the United States seeks a just, secure, and sustainable two-state solution,” she told the crowd, though she didn’t highlight that many other Democrats also signed on to the bipartisan resolution.

In 2018, she attended the conference again, this time giving an off-the-record address that was recorded and shared on social media by several attendees. In her speech, she made a surprising revelation: “As a child, I never sold Girl Scout cookies, I went around with a JNFUSA box collecting funds to plant trees in Israel.”

JNFUSA stands for the Jewish National Fund-USA, the US branch of a nonprofit organization founded in 1901 with the express mission of purchasing land in Ottoman-controlled Palestine to be used to form a future Jewish state. The organization played a major role in pushing Palestinians out of their lands to make way for the state of Israel.

To raise money for this effort, “Jews the world over collected coins in iconic JNF Blue Boxes, purchasing land and planting trees until ultimately, their dream of a Jewish homeland was a reality,” the JNF notes on its website.

Right now: @KamalaHarris speaking at @AIPAC!! 2020!! pic.twitter.com/pcQPwxhmjr

— Elan Karoll (@elankaroll) March 5, 2018

In more recent times, the JNF has courted controversy over allegations that it funds development projects in Jewish settlements in the Israeli-occupied West Bank — settlements that are illegal under international law and that have been opposed by both Democratic and Republican US administrations.

And while she skipped the 2019 conference, as many Democratic presidential hopefuls did, she still hosted California AIPAC members in her Senate office that March to discuss, among other things, “the need for a strong U.S.-Israel alliance” and “the right of Israel to defend itself.”

Great to meet today in my office with California AIPAC leaders to discuss the need for a strong U.S.-Israel alliance, the right of Israel to defend itself, and my commitment to combat anti-Semitism in our country and around the world. pic.twitter.com/83Yrrbw4Q8

— Kamala Harris (@SenKamalaHarris) March 25, 2019

Soifer, the former national security adviser who is now the executive director of the Jewish Democratic Council of America, told me that Harris’s views on Israel “go beyond just the security relationship, of which she’s very supportive.”

She pointed me to Harris’s November 2017 trip to Israel. Soifer was with the senator and watched Harris try to improve ties between California and Israel’s technology sectors. What most struck Harris, Soifer said, was how Israeli companies had made strides in conserving water, an issue California has struggled with and that the senator is deeply interested in.

In her 2019 book, Harris wrote about a subsequent trip she took to Israel to delve deeper into water conservation issues:

There’s a lot we can learn from friends and partners who have already made such investments—especially Israel, a global leader on water security issues. In February 2018, I traveled to Israel and toured its Sorek desalination plant, which uses reverse osmosis to produce clean drinking water from the sea. I had a glass. It tasted as good as any water I’ve ever had.

Harris received a lot of criticism for her 2017 Israel trip, mainly because she met with Netanyahu. Soifer said Harris took the meeting because, whether Harris liked him or not, Netanyahu was the elected leader of the country. “They had a good meeting, a lengthy meeting,” she told me, noting Harris pushed Netanyahu not to unilaterally annex any territory.

Today I met with Senator @KamalaHarris of California. We discussed the potential for deepening cooperation in water management, agriculture, cyber security, and more. I expressed my deep appreciation for America’s commitment to Israel’s security. pic.twitter.com/L5qdcgwWG0

— Benjamin Netanyahu (@netanyahu) November 20, 2017

Soifer said that trip, and Harris’s decision to meet with Netanyahu despite the criticism, is a testament to the senator’s fearlessness on the world stage. “She’s truly a leader and does what she thinks is right and is not persuaded by what other people think,” she told me. Still, Harris will have to walk a fine line between maintaining the US-Israel relationship and keeping certain Democratic activists happy by pushing back on Netanyahu’s anti-Palestinian policies.

Of course, Harris has many more foreign policy stances. Like Biden, she aims to end the war in Afghanistan, reenter the Iran nuclear deal as long as Tehran is in compliance with it, keep North Korea from advancing its nuclear arsenal, allow more refugees in from places like Venezuela, and much more.

But it’s her major agreements with Biden — and the other areas where Harris might gain notoriety, both good and bad — where her foreign policy views most matter. She may not be a very powerful vice president when it comes to global affairs, but she’ll likely make her views heard, one way or the other.

Will you become our 20,000th supporter? When the economy took a downturn in the spring and we started asking readers for financial contributions, we weren’t sure how it would go. Today, we’re humbled to say that nearly 20,000 people have chipped in. The reason is both lovely and surprising: Readers told us that they contribute both because they value explanation and because they value that other people can access it, too. We have always believed that explanatory journalism is vital for a functioning democracy. That’s never been more important than today, during a public health crisis, racial justice protests, a recession, and a presidential election. But our distinctive explanatory journalism is expensive, and advertising alone won’t let us keep creating it at the quality and volume this moment requires. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will help keep Vox free for all. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Alex Ward

Read More