How can some places use the federal holiday to honor “human rights” and Confederate generals — and not the civil rights leader?

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/15986155/Vox_The_Highlight_Logo_wide.jpg)

Welcome to Laboratories of Democracy, a series for Vox’s The Highlight, where we examine local policies and their impacts.

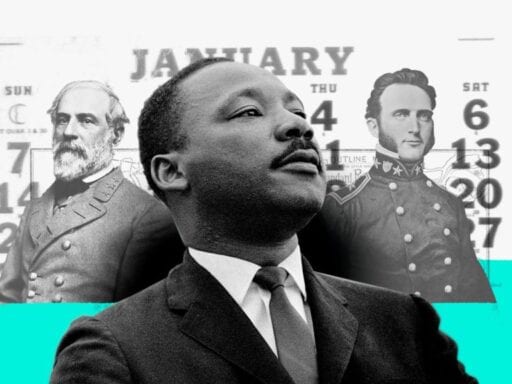

The policy: States have stretched the meaning of the federal Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday to honor everything from “human rights” to Confederate generals.

Where: Alabama, Mississippi, Utah, Idaho, Virginia, New Hampshire

Since: 1986

The problem:

In March 1990, the NFL delivered Arizona an ultimatum. The league approved Phoenix as the host of the 1993 Super Bowl — a sure economic boon — on one condition: The state needed to finally recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day as a holiday.

In a scramble, state legislators placed MLK Day on the ballot in 1990, confident it would be approved. But when the vote tally came in that November, officials were shocked to discover the proposal had failed. “We honestly don’t believe our kids and grandkids should revere him as a national hero,” one anti-MLK Day activist told the New York Times. True to its word, the NFL pulled the 1993 Super Bowl from Arizona.

The Arizona vote revealed something sinister about American race relations: Although MLK Day is generally viewed as a way to mark the country’s supposed racial progress and the life of King, who fought for that progress, many white Americans still refuse to honor the civil rights leader.

States are not required to observe any of the 10 federal holidays, including Martin Luther King Jr. Day. In many cases, they don’t: Columbus Day, for example, is only recognized in 21 states. But state authority over how to designate holidays has given rise to an ominous downplaying of MLK’s legacy.

Congress first considered making Martin Luther King Jr. Day a holiday in 1968, the year of the civil rights leader’s assassination. Annual bills were introduced for more than a decade, but none of them made it out of committee because of lingering hostility toward King, particularly among several Republican representatives. But activists and labor unions continued to push for the holiday, delivering a petition that garnered more than 6 million signatures to Congress in the early 1980s. President Ronald Reagan had initially opposed MLK Day, citing the cost of another paid holiday for federal workers, but after the Reagan administration’s campaign against affirmative action and welfare, the president decided he needed to shore up his black support somehow. In 1983, he signed a law proclaiming that the third Monday of January would become Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

But contempt for King’s legacy remained. Much of it stemmed from an insistence that King’s work in desegregating the South and advocating wealth redistribution across the country was fundamentally “un-American.” Misinformation about King as a communist sympathizer spread widely. Although many states followed the example of Congress and quickly recognized a holiday in his honor, some of the holdouts decided to get creative.

How it works:

In April 1984, a pair of white supremacists crawled under a synagogue in Boise, Idaho, and placed three sticks of dynamite beneath the kitchen. The duo, members of the violent white nationalist organization Aryan Nations, later said they intended it as an “act of war.” When the bomb went off, no one died. But it became one in a string of Aryan Nations attacks, which included the murder of a Jewish radio host, that shook the nation in the mid-’80s.

The festering racism in Idaho, one of the whitest states in the country and the main base of the Aryan Nations, became fodder for national news stories. The state needed an image change, so Idaho Gov. John Evans devised a simple solution: Idaho would, at long last, push for a holiday to honor Martin Luther King Jr. after years of refusing to recognize it.

But the legislation to make MLK Day official didn’t pass. The legislature tried in 1986, then again in 1987, and in 1989. Opposing legislators claimed they were concerned about cost, but as Boise State University history professor Jill K. Gill noted in The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, many Idahoans distrusted King, if not civil rights in general. In King, they saw a man who had committed marital infidelities and supposedly harbored communist sympathies. But other legislators did not bother to hide that their opposition was rooted in racism. State Rep. Emerson Smock complained to the Post Register, “A black holiday is what they’re wanting.”

The legislature eventually forged a compromise: Rather than create a state holiday that honored King alone, the state would broaden it to include, in theory, anyone. In April 1990, the state announced it would celebrate King’s birthday as “Martin Luther King Jr.-Idaho Human Rights Day.” Although King remained the primary honoree, the extended name was explicitly about mollifying King’s detractors.

Idaho isn’t alone. Alabama and Mississippi still celebrate a “King-Lee” day that lumps King together with Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee, whose birthday is January 19. Until 2000, Virginia took this idea even further, creating a “Lee-Jackson-King Day” that also honored Confederate leader Stonewall Jackson.

“Bundling the holidays remains a form of resistance to racial justice in America,” Gill told Vox. By putting King alongside Lee, she added, “it also remains a vehicle for obscuring white supremacist aims, past and present.”

Other states tried an array of strategies to quite literally take Martin Luther King Jr. out of Martin Luther King Jr. Day. Until 2000, Utah’s holiday did not mention King by name: MLK Day was known simply as Human Rights Day. South Carolina took a different tack, passing a standalone holiday honoring the civil rights leader but making its observance optional. There, state workers could choose between MLK Day and three separate Confederate holidays as their paid day off.

Arizona voters, by contrast, refused to approve a ballot proposal for MLK Day until 1992, two years after the NFL boycotted the state. And in 2000, New Hampshire became the last state in the country to recognize Martin Luther King Jr. Day under any name, closing out an effort that included multiple failed bills since 1979. The winning compromise: New Hampshire would call its holiday “Martin Luther King Jr. Civil Rights Day” instead of just “Martin Luther King Jr. Day.”

Attempts to lump King together with other historical figures have not disappeared. In 2010, the Utah legislature considered a bill that would add gun manufacturer John Browning to the state’s celebration of King. When Desert News asked Senate Majority Leader Scott Jenkins whether he saw any conflict in honoring a gun manufacturer alongside a proponent of nonviolence, Jenkins replied, “Guns keep peace.”

Many of the same states that have renamed MLK Day also routinely downplay anti-black violence in their discussions of America’s past. According to the Washington Post, Massachusetts, which observes the holiday, mentions slavery 104 times in its K-12 public school history guidelines. Compare that to Alabama, which only mentions it 15 times, or Idaho, which only mentions it twice. Meanwhile, in New Hampshire, key events in the civil rights movement like the murder of Emmett Till have at times been ignored entirely. According to Gill, maintaining a joint King-Lee holiday “continues that tradition of prioritizing white people’s reconciliation and image of patriotic nobility over acknowledging the historical truths of racial injustice and culpability.”

Black activists have long pointed out the ways political leaders have diluted King’s legacy on his birthday. Instead of focusing on his commitment to radical policies like wealth redistribution, politicians are quick to generalize King as a unifier, proof of America’s supposedly harmonious racial present. Three years ago, the FBI even tweeted its support for King’s “incredible career fighting for civil rights” — even though the agency cast King as a domestic threat during his lifetime.

That some states still refuse to celebrate King, even in this diluted form, is perhaps an indictment of how far America remains from any semblance of racial equality.

Michael Waters is a writer covering the oddities of politics and economics. His work has appeared in the Atlantic, Gizmodo, BuzzFeed, and the Outline.

Author: Michael Waters

Read More