The most influential show of the 2010s was ruined by one man’s dick.

Had you asked me in 2015 to name the frontrunner for my favorite show of the 2010s, I wouldn’t have hesitated — FX’s Louie.

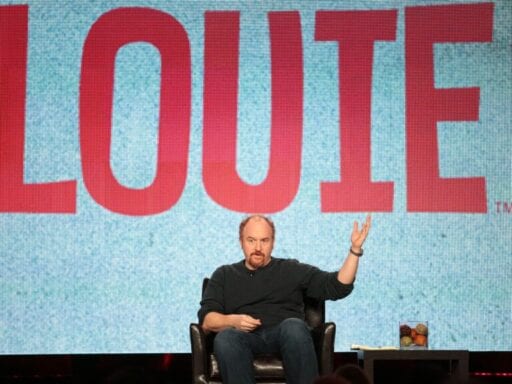

The unusual and pathos-laden comedy was the brainchild of Louis C.K., who wrote, directed, starred in, and produced every single episode (in addition to having several other roles behind the scenes). It was groundbreaking and hugely influential, winning extensive critical acclaim and several Emmy Awards. The way that every episode functioned as a short film unto itself was a welcome relief from the endless ocean of over-serialized shows that ultimately told empty stories.

Particularly in its second and third seasons, Louie seemed to evince an all-consuming empathy for humanity, undercut with a healthy sense of self-loathing on the part of C.K. himself. Indeed, the more plaudits he amassed, the more he seemed willing to portray himself as a truly loathsome person.

But the longer the show ran, the more the bloom came off the rose. Louie’s fourth season (which aired in 2014) frustrated some critics as it waded into fraught territory regarding issues of sexual consent without seeming to have much of a map. For me, though, C.K. deserved room to explore, based on those earlier seasons. I didn’t agree with everything the show had to say, but I wanted to give him freedom to explore complicated emotions that human beings might have around love and sex. He’d earned my trust, right?

A few years later, if you look at my list of the seminal TV shows of the 2010s, Louie isn’t on it. Many of the shows that were influenced by it are there — from Girls to Atlanta to Fleabag — but Louie itself is not. And I’m not the only critic who excluded it. The A.V. Club (where I reviewed the show’s fourth season) not only didn’t recognize Louie as a top show of the decade but didn’t make room for it on a list of 100 top shows.

Louie might have been groundbreaking. It might even still be a good show. But all of the trust C.K. had earned with me dissipated in an instant in 2017, when he confessed to masturbating in front of multiple women without their consent, then began a long, public tour of insisting he wasn’t so bad after all. (FX canceled Louie soon afterward.) Louie might have been hugely influential, but it was ruined by its creator’s dick.

Some shows can survive a massive scandal involving their major creative force. Most can’t.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/assets/4446071/Screenshot_2014-05-13_09.20.45.png) FX

FXNot every work of art will automatically be destroyed by bad behavior on the part of someone involved in it. Let’s compare C.K.’s downfall with accusations of sexual harassment leveled against Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner. Weiner’s voice is present in every single frame of Mad Men. But, crucially, he’s not onscreen, and the show’s storytelling is not subtly trying to sell us on his worthiness as a human being. You can watch Mad Men without thinking about Weiner, no matter the accusations against him. You can’t watch Louie without thinking about Louis C.K.

And thinking about Louis C.K. now means thinking about his victims, about the women he hurt, both through his behavior and through his attempts to cover it up. Many were fellow comedians whose careers he damaged or ended by scaring them out of the industry. To think about Louie is to think about the esteem that powerful men have always accrued almost as a matter of course.

But Louie’s tainted legacy extends beyond C.K.’s appearance in every episode. Louie isn’t just a show about one guy taking on the world. It’s a show about how one man, flawed though he might be, helps viewers understand the world as he sees it. The appeal of Louie always relied on the audience believing that C.K. himself might get frustrated with his fellow human beings — and then seeing him always, upon reflection, find their humanness. That appeal began to disintegrate after his bad behavior came to light.

But don’t take my word for it; take 2015 Emily VanDerWerff’s word for it. At the time, she wrote:

The other show that most marks this new era is FX’s comedy Louie… The brainchild of comedian Louis C.K., who writes, directs, and stars in every episode, Louie essentially forces the audience to have empathy with its titular character, because he’s the only character who appears in every episode. Louie’s not a bad guy to hang out with. As a comedian, he’s fascinated by people from all walks of life, and he’s always trying to figure out what makes them tick. And every episode of Louie presents the other figures in his life not as worthy of ridicule but as worthy of understanding.

Louie was so tied to Louis C.K. that when he became a figure who prompted, at best, mild distaste, the show itself was ruined by the disconnect between who C.K. sold himself as and who he actually was. (A similar fate befell The Cosby Show and Bill Cosby, even though Cosby played a wholly fictional character on that series.) As Sonia Saraiya memorably wrote for Variety, it was easy to believe in Louis C.K., which made it all the more difficult to listen to anything he had to say after the world learned how much he’d been lying all along.

I think a lot about when I first became aware of the accusations against C.K. — during the show’s third season, when they were still unconfirmed rumors that hadn’t explicitly been attached to him (though he was considered the most likely candidate for the rumors to be about). I was insistent on trusting my own friends’ stories about their encounters with horrible men, but it took me so long to actually accept that he had done what he had done. I didn’t want to believe. I wanted Louie to be “real.” So when the show turned out to be a sham, I was angry at myself for subscribing to lies because they were told in a language that made me unwilling to hear the truth.

As the 2010s conclude, we’re probably still too close to the reveal of C.K.’s repulsive behavior to know how history might eventually regard his art. In late 2017, as the waves of revelations that became the Me Too movement broke forth, the temptation was to say that things had changed, that Hollywood would no longer settle for business as usual. But we know too well that we can’t believe that was remotely true. Hollywood has always been good at worming its way back to the status quo. So many of the men singled out in the midst of Me Too still have thriving careers. And even if C.K. saw his TV opportunities dry up, he was able to return to the stand-up comedy circuit, where he recently said he’d rather be in Auschwitz than present-day New York City. All right, man.

Independent of C.K.’s downfall, Louie was the kind of show that loses its luster as time goes on. It was so tied to the era in which it aired that it was already losing some of its potency by its fifth season. By then, other shows had come along to push the series’s ideas even further, to experiment more with the TV comedy form. In a world where C.K. remained one of our leading artistic figures, where he was a complete saint who really was the guy he seemed to be on TV, Louie might have still been seen as a pioneer, even after it was inevitably displaced.

But we don’t live in that world. We live in a world where we got to see the real Louis C.K., and when he had a chance for maybe a 10th of the grace he used to display as his fictional self on TV, he turned nasty instead. Louie’s legacy now isn’t one of empathy and groundbreaking television; it’s instead one of how horrible it is to realize that a man who promised you everything was always a sleazy con.

Author: Emily Todd VanDerWerff

Read More