The Irishman is the peak of the director’s lifelong obsession with the sacred and profane.

Near the end of Martin Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, Jesus (played by a young but craggy Willem Dafoe) is dying on the cross when he’s approached by a young girl; she says she’s his guardian angel. God has tested him and is pleased, the angel tells Jesus, and there’s no need now for him to die. He can go live a simple life.

And so Jesus does, heading straight to Mary Magdalene’s side. Soon they have children, a home, a quiet and happy existence.

When, all at once, Mary Magdalene dies, Jesus finds his way with the angel’s help to the home of sisters Mary and Martha, whose brother Lazarus he once raised from the dead. There he embraces Mary and continues this life, eventually in what seems to be a polygamous relationship with both sisters. They have more children. He is happy.

But the doubts that plagued Jesus in his former life still haunt him now, and he tells the angel about them. “I’m ashamed when I think of it,” he says. “Of all the mistakes I’ve made. Of all the wrong ways I looked for God.”

The wrong ways I looked for God.

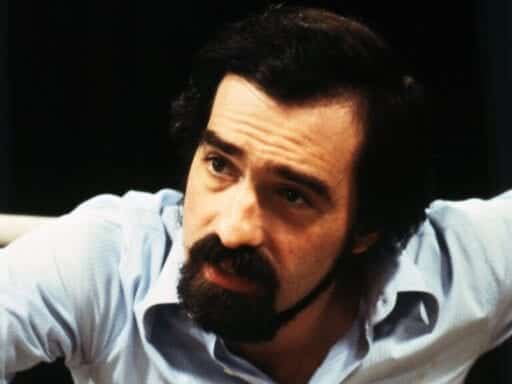

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19410964/607433676.jpg.jpg) Universal Pictures/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images

Universal Pictures/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty ImagesAs the movie meanders toward its conclusion, we come to realize along with Jesus that he’s been tricked — that the “angel” was actually Satan is disguise, a last temptation for him — but that he also seems to have hallucinated the whole thing. Horrified, he snaps back to reality, finding himself still dying on the cross for the salvation of mankind.

The ending is purposely ambiguous and haunting, fitting for a movie about a man haunted by his divine nature. The Jesus of Last Temptation is in some ways the ahistorical Jesus of most cinematic adaptations — light-haired, blue-eyed — but he’s not an otherworldly wise being who seems certain and confident of his calling. Instead, he is most definitely a man, one with hungers and headaches and lusts and, above all, fears.

He’s still the son of God; he can perform miracles. But he seems scared of the miracles, too. The dual natures within him are tearing him apart. He aches to die and be put out of his misery, or to simply be able to give in to one side of his nature. Jesus’s “last temptation” isn’t to have sex, as some of the film’s detractors claimed; it’s to give in to his desire to lead the life of a man, sapped of the sacred. To lead, in the less explosive sense of the word, a profane life.

Those two sides of Christ, sacred and profane, is what Greek novelist Nikos Kazantzakis wanted to explore in his 1952 novel on which the movie is based. In the preface that opens the novel, Kazantzakis writes, “The dual substance of Christ — the yearning, so human, so superhuman, of man to attain God … has always been a deep inscrutable mystery to me. My principal anguish and source of all my joys and sorrows from my youth onward has been the incessant, merciless battle between the spirit and the flesh … and my soul is the arena where these two armies have clashed and met.”

Scorsese — who told a studio executive that he wanted to make Last Temptation to know Jesus better — chose that text to open the film, too. It appears in bold white lettering, line by line, on a black screen before the film begins. The Last Temptation of Christ mattered so much to Scorsese that he continued to pursue making it for years through nearly insurmountable struggles, from funding troubles to lost studio backing, to cancelled locations and protests and loud condemnation from Christian conservatives.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19410954/515946023.jpg.jpg) Photo by Barbara Alper/Getty Images

Photo by Barbara Alper/Getty Images“It is more than just another film project for me,” Scorsese said in a public statement in 1988 as the outcry reached a fever pitch. “It was made with conviction and love and so I believe it is an affirmation of faith, not a denial. Further, I feel strongly that people everywhere will be able to identify with the human side of Jesus as well as his divine side.”

Though it refers specifically to Last Temptation, the statement works as a guiding light for Scorsese’s entire filmmaking career. He’s a humanist who favors complexity over caricature, but he’s not just interested in his characters’ human side. For him, people are imbued with both a human spirit and a spark of the divine; we’re not Jesus, but we’re like him, and what he struggled with, we struggle with, too. It’s the wrestling between those two natures, the battle between worldly desires, like power and money and sex, and more transcendent preoccupations, like salvation, that makes up our lives.

That tension explains a lot about Scorsese’s movies, which range wildly in their settings and genres: He’s made lush period dramas (like 1993’s Edith Wharton adaptation The Age of Innocence); paradigm-busting vigilante stories (1976’s Taxi Driver); uncomfortably bleak comedies (1983’s The King of Comedy); commercial thrillers (2010’s Shutter Island); documentaries (such as 1976’s The Last Waltz); musicals (1977’s New York, New York); children’s films (2011’s Hugo); madcap tragicomedies (like 1990’s Goodfellas), and some of the most iconic gangster movies of all time, from Mean Streets (1973) to The Departed (2006). In all of those genres, Scorsese uses the setting of a self-contained world (Wall Street, New York high society, remote Tibetan or Japanese villages, New York City’s Italian-American community) to look at the consequences of our choices over time, and to explore how our interactions with the sacred and profane shape our souls.

So of course it’s Scorsese who brought to the screen some of the most iconic anti-heroes in movie history, including Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver, Jake LaMotta from Raging Bull, Rupert Pupkin from The King of Comedy, and Jordan Belfort from The Wolf of Wall Street; all men who desperately want to make something of themselves, and lose it when the world doesn’t comply. And Scorsese’s trilogy of spiritual films — The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Kundun (1997), and Silence (2016) — as well as the deeply religious probings in a number of his other films (including Mean Streets and Raging Bull) have established him as one of the most significant religious filmmakers of all time as well.

Which is why The Irishman is such an important skeleton key to unlock Scorsese’s oeuvre. 2019 was a banner year for the filmmaker, who turned 77 on November 17. Not only did he direct two films released this year (in addition to The Irishman, his Bob Dylan documentary Rolling Thunder Revue came out in June), but he also served as producer for four other films, several of which number among the year’s best: The Souvenir, Port Authority, Once Were Brothers: Robbie Robertson and the Band, and Uncut Gems, which has generated Oscar buzz for star Adam Sandler. And one of the year’s highest-grossing films, Joker, draws directly and explicitly from Taxi Driver and The King of Comedy.

In 2019, Scorsese also managed to stoke the ire of Marvel’s fans, stars, and directors when he criticized the way that Marvel’s cinematic universe has altered Hollywood’s priorities — which, in a way, only underlines how important he is to cinema. He’s more than one of its most influential directors; Scorsese has devoted his energy to the preservation of world cinema through his Film Foundation and the promotion of otherwise underserved directors from around the globe with his World Cinema Project too.

But The Irishman — a mobster epic that evolves into something quite different by the end — feels like more than just another Scorsese movie. It’s more of a culmination of what’s occupied Scorsese, almost single-mindedly, for so many decades. To paraphrase the words of Last Temptation’s Jesus, Scorsese, who once sought a life as a priest, has spent his life as a filmmaker instead exploring all the wrong ways we look for God (and some of the right ones, too).

The Irishman blends together several of Scorsese’s favorite filmmaking modes, always with an eye toward God

The Irishman is longer than most feature films, at three and a half hours, but there’s a good reason for that. The first two-thirds or so of the film is a swaggering chronicle of the life of Frank Sheeran (Robert De Niro), a hitman for crime syndicate boss Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci) and then for Teamster boss Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino), told through Sheeran’s eyes. This story is long enough to fill out an entire film and, in many ways, feels like a pleasurable retread of territory covered in Goodfellas. The wealth and, most importantly, power that comes along with associating with Bufalino and Hoffa is attractive to Sheeran, and he’s happy to make them his life’s focus.

But when you’ve finally been tricked into thinking this is the whole movie, it suddenly starts to shift. One theme of Scorsese’s mobster movies has always been the male camaraderie, loyalty, and even love that comes along with being part of a “family” — that organized crime is attractive not just for profane reasons (the money, the sex, the swagger) but also for what we might call sacred ones. Invariably, his characters are Catholic but cavalier, believing in God and the church without living particularly pious lives. But the love they find in their associations with one another is, in its own way, a reflection of something divinely inspired.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19410976/156479024.jpg.jpg) Warner Brothers/Getty Images

Warner Brothers/Getty ImagesThat same genuine friendship and care emerges in The Irishman, mostly between the men. But they’re also largely blind to how their egos and power trips are hurting the women and children they’re supposed to love, even as they delude themselves into thinking they’re doing right by their families. In the final stretch of the film, the pain they’ve caused, and the impossibility of atoning for it, is made achingly clear.

This all happens as Frank is watching his old group of comrades become old, ill, and sometimes die without him even realizing it happened till much later. There are moments that recall the aged Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull sitting in front of a mirror, alone, trying to come to terms with the life he’s derailed through his vices and addictions. (“That’s the beginning of God listening to him,” Scorsese once explained of that scene in Raging Bull. “But he’s got to forgive himself first. And a lot of people can’t do that. I struggle with that. We all do.”) Others seem reminiscent of a late scene in Last Temptation, when Jesus’s disciples, now old, show up at his deathbed and aren’t entirely sure whether to revere him or be angry at him for abandoning them.

Frank can see the end coming, but can’t quite believe this feeling of slowly diminishing into nothingness is the way that his life will end, even as he ends up in assisted living. Quietly, his Catholicism begins to reemerge, with the possibility of an afterlife. He struggles, with a priest, to acknowledge that he’s done anything wrong. It seems he starts to wonder if God has anything in store, and if he should have been living his life with that in mind, and if God is quiet or he’s just lost the ability to listen — the question that occupies not just the Jesus of Last Temptation but the priests in Silence and many others throughout Scorsese’s body of work.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19239905/irishman2.jpg) Netflix

NetflixThat’s why, in a way, it feels as if The Irishman works as not just Frank’s story but Scorsese’s, too. He’s been far more self-reflective throughout his life than Frank, and he talks freely about moments of spiritual and physical crisis and the ways his faith has wavered and grown.

Yet The Irishman still reads as a plea for understanding from his audience. It’s a deep dive into how one side of human life is the drive for power and sex and money, and the other side is a deep yearning for love and grace.

Frank’s life is littered with the wrong ways to search for God, but he’s hit by accident on some of the right ones, too. And looking at The Irishman, you can see hints of Scorsese’s wrestling in his own soul and echoes of his work, which he always seems to intend for one audience alone in the end: God.

The best way to get the full effect of The Irishman, which premieres on Netflix on November 27, is to prep yourself by watching a handful of Scorsese’s films — the ones that help illuminate the themes he wraps into this epic. With that in mind, here are six of Scorsese’s movies worth watching before you see The Irishman, and why (and how). Some probe the duality of the soul in the context of mobsters and angry men; some juxtapose the sacred and profane; some are contemplative masterpieces that explore spiritual realities. All help show the breadth of Scorsese’s body of work, and the importance of The Irishman to his career.

Mean Streets (1973)

Mean Streets stars frequent Scorsese collaborator Harvey Keitel as Charlie, who works for his loan shark uncle, mostly collecting on debts, while trying to scrape out a living on New York City’s Lower East Side. He feels responsible for his friend Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro, in his first appearance in a Scorsese film), a whirling dervish of a man who owes money all over the place and ends up getting Charlie in trouble.

Meanwhile, Charlie is a devout Catholic, who — in a theme that will repeat itself throughout Scorsese’s work — is torn between his faith and the realities of the line of work he’s in, not to mention his secret affair with Johnny Boy’s cousin Teresa. “The pain in hell has two sides: the kind you can touch with your hand, the kind you can feel in your heart; your soul, the spiritual side,” Charlie says in voiceover. “And you know, the worst of the two is the spiritual.”

How to watch it: Mean Streets is streaming on Netflix and available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

Raging Bull (1980)

Raging Bull is about the life of boxer Jake LaMotta (Robert De Niro), cutting back and forth between LaMotta’s bloody fights in the ring and his slow self-destruction in his personal life, from rage and abuse of his wife to drinking, drugs, and extreme jealousy. Scorsese often juxtaposes LaMotta’s baser desires with his Catholicism, to humorous effect — for instance, he meets his second wife Vicky at a church dance; on their first date they rather euphemistically lose a ball in the minigolf hole that is shaped like a church; and we often watch Jake and Vicky in various states of undress in the door to the bedroom, which is flanked by kitschy portraits of Jesus and Mary. You can also read a need to purify himself through blood — a fundamentally religious concept — in LaMotta’s intense bodily trauma in the ring.

But the most surprising thing about Raging Bull — not, for all of its references, overtly a film about religion — may be the very end. After LaMotta leaves the frame for the last time, white letters emerge onto the black screen that quote John 9:24-26 in the Bible (followed by a dedication to one of Scorsese’s NYU professors):

So, for the second time, [the Pharisees] summoned the man who had been blind and said: “Speak the truth before God. We know this fellow is a sinner.”

“Whether or not he is a sinner, I do not know,” the man replied. “All I know is this: once I was blind and now I can see.”

How to watch it: Raging Bull is streaming on Netflix and available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

The Last Temptation of Christ (1988)

Greeted by protests for months before and after its release — in France, one cinema showing the film was firebombed by conservative Christian activists — The Last Temptation of Christ is remembered at least as much as a lightning rod for culture war controversy as a religious film. But with the distance of time, it’s clear how personal the movie is to Scorsese, and how assiduously he tries to respect the character of Jesus, even in the midst of a daring story that reimagines Jesus (played by Willem Dafoe) as a struggling human man rather than the ethereal being of Hollywood’s (and many Christians’) imagining. The Jesus of Last Temptation is beset by fears, constantly changing his mind about how to approach his work on earth, and anything but courageous.

Yet it’s important to be conscious of Scorsese’s own spiritual journey through the making of film; after all, he told a studio executive that he wanted to make it so that he could understand Jesus better. (The screenplay was written by his Taxi Driver and Raging Bull collaborator Paul Schrader, who would go on to work with Scorsese again on Bringing Out the Dead and also write and direct 2018’s best religious drama, First Reformed.) In his way of thinking, Jesus is a figure worth knowing (and religion a thing worth holding on to) because Jesus was a man as well as God. So when men who aren’t divine, but harbor a bit of the divine spark, look back on their sinful lives, Jesus can sympathize with them. It’s a compassionate, risky, and thoroughly heartfelt film.

How to watch it: The Last Temptation of Christ is available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

Goodfellas (1990)

Of all of Scorsese’s films, Goodfellas may be the one with the most obvious parallels to The Irishman. It’s the tale of ambitious young Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) who, from his youth, desires nothing so much as a life among the mobsters he idolizes. Goodfellas chronicles his rise among a group of men led by Paulie Cicero (Paul Sorvino) and close associates Jimmy Conway (Robert De Niro) and Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci).

De Niro and Pesci had worked together before (notably in Raging Bull, where Pesci played LaMotta’s brother) and would reunite for Casino in 1995 and, decades later, for The Irishman. But it’s really the tone of Goodfellas that’s revived by The Irishman: the bluster and saunter of men who believe themselves to be at the top of their world, at least until that world starts to come crashing down. Everyone sort of gets their comeuppance at the end of Goodfellas, but it took until The Irishman for the glamour of Goodfellas to get balanced out with something more reflective.

How to watch it: Goodfellas is available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

The Age of Innocence (1993)

The links between The Age of Innocence and The Irishman may be less obvious than those of some of the other films in Scorsese’s canon. A romance? A costume drama set in the Gilded Age in New York?

But this Edith Wharton adaptation — which follows the passionate but unconsummated love affair of Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) and Countess Ellen Olenska (Michelle Pfeiffer), following Archer’s engagement to socialite May Welland (Winona Ryder) — is a forerunner in a couple of ways. It’s a study of desire, of a man from an insular community who wants more than that world is presenting to him and isn’t certain whether he can or should take it for himself. And its ending reveals how Archer’s choices, over time, have affected his life and character, in ways that are both good and devastating. It is one of Scorsese’s finest meditations on living a full life.

How to watch it: The Age of Innocence is available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

Silence (2016)

Scorsese’s 2016 religious epic is based on Shūsaku Endō’s novel Silence, first handed to him by an Episcopal priest following the Last Temptation controversy. The book became an obsession of Scorsese’s for more than 25 years, and no wonder: It is a slippery, troubling story about the silence of God, set among Portuguese priests and persecuted Christians in 17th century Japan. Two young priests (played by Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver) arrive in Japan in search of their mentor (Liam Neeson), who has gone missing and is rumored to have apostatized. When they arrive, they discover the enormous turmoil and persecution faced not just by the priests, but the Christians in Japan, from a government bent on keeping Western influence out.

Silence navigates the tension between missionary and colonizer, East and West, Christianity and Buddhism and political ideology, but refuses to land on definitive answers. The struggle for faith in a world marked by suffering and God’s silence is present in every frame of Silence. The answers in Scorsese’s film, as in Endō’s novel, are found not in words, but in the spaces between them.

How to watch it: Silence is available to digitally rent or purchase on Amazon, YouTube, Vudu, Google Play, and iTunes.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More