Supporters of the initiative hoped it would depolarize the state’s elections.

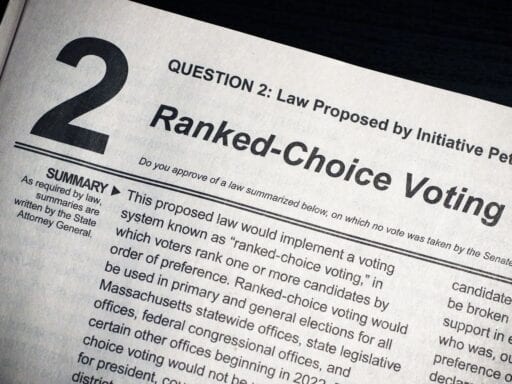

Voters in Massachusetts have rejected the ballot initiative Question 2, which would have implemented ranked-choice voting in the state.

Had the vote succeeded, all Massachusetts primaries and general elections for state and federal congressional seats; state executive officials; and county offices would have been held using the method.

“We came up short in this election, and we are obviously deeply disappointed,” Cara Brown McCormick, the Yes on 2 campaign manager, said in a statement conceding the race.

Ranked-choice voting works like this: Instead of just picking one of the candidates on the ballot, you rank them from most preferred to least preferred. While it is new in the United States, it has been successfully used for a century in Australia and in Ireland.

The idea is that this allows voters to choose their favorite possible candidate. Most of the United States has what’s called a first-past-the-post electoral system, where the candidate who receives the most votes becomes president. First-past-the-post systems incentivize strategic voting (voting not for your favorite candidate but for your preferred candidate with a real shot at victory), and they have driven the rise of a two-party system like the one in the US.

And while first-past-the-post voting systems are not the only factor that has led to the two-party system or to the increasing polarization of America, they’ve certainly contributed. First-past-the-post systems mean that third-party candidates rarely win, even if many voters prefer them; each voter expects that a vote for the third party would be “throwing away” their vote.

Imagine a person were voting between President Donald Trump, Democratic nominee Joe Biden, Green Party candidate Howie Hawkins, and Libertarian Party candidate Jo Jorgensen. Our hypothetical voter likes both Hawkins and Jorgensen better than Biden but would rather Biden win than Trump.

Under first-past-the-post voting — the voting system most Americans voted with this election — our hypothetical voter might feel forced to vote for Biden. Under ranked-choice voting, they would list (for example) Hawkins first, Jorgensen second, Biden third, and Trump fourth. When ballots are counted, the ballot counters will eliminate the candidate with the fewest first-place votes and “move” their vote to their second-place candidate.

You can see how it works on this ballot from Maine, which conducted the first-ever general statewide election conducted with ranked-choice voting this November.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21993563/media_7e9cf132d236443bbc05d22b40af96a7Election_2020_Maine_Ranked_Voting_89453.jpg) David Sharp/AP Photo

David Sharp/AP PhotoAs a result, third-party candidates get more votes since voters don’t feel that they’re throwing their vote away by supporting the third-party candidate. And the process generally favors candidates who lots of voters find acceptable over polarizing candidates who many voters hate.

“Ranked-choice voting rewards candidates who can appeal most broadly because candidates compete to be voters’ second and third choices as well as their first,” voting reform expert Lee Drutman wrote for Vox in 2019. Studies find that in areas with ranked-choice voting, campaigns are more civil. Ranked-choice voting might also increase representation of women and minorities, who seem to benefit when the electoral conditions encourage coalition-building.

A growing conversation about how we vote

Ranked-choice voting is used all over the world, but until two decades ago — when San Francisco adopted it — it was rarely used and rarely discussed in the US.

US election experts, concerned about growing polarization and voter disenchantment, began encouraging other cities and states to adopt it. It did nicely in San Francisco, and other cities signed on. Eventually, the movement hit the national stage: In 2018, Maine became the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting. In 2019, New York City signed on as well. In the 2020 election cycle, presidential candidates Sens. Elizabeth Warren and Michael Bennet endorsed it.

These early adopters allow us a window into some important questions about ranked-choice voting. In particular, critics have worried it will be harder for the election office to tabulate and that it will confuse voters or lead to more spoiled ballots.

No such problems were reported in this year’s new ranked-choice primaries, and ranked-choice voting works fine in many other countries. But this year’s high-turnout statewide general election in Maine will represent the system’s first time in the spotlight for most Americans. If it performs well, it may be on the ballot in more states next election.

Author: Kelsey Piper

Read More