Democrats plan to improve Medicare benefits as part of their reconciliation bill. But there’s a lot of work to do.

Medicare is one of America’s flagship government programs, immensely popular with the public, a critical safety net for people over 65 — and it is full of holes.

The program’s benefits are not as comprehensive as most other kinds of health insurance Americans carry. Unlike with commercial health insurance or with Medicaid, which covers people in or near poverty, there may not be a limit on what a person on Medicare may have to pay out of pocket for their medical care.

Medicare also doesn’t cover dental or vision services, which are essential to the health of the over-65 population that it serves. The benefits for long-term care are meager, placing an enormous financial burden on patients and their families.

Two things can be true at once: Medicare has been a tremendous success in eliminating poverty from medical expenses among the elderly, compared to the pre-1965 status quo, and it is, as currently constructed, woefully inadequate to the realities of modern health care.

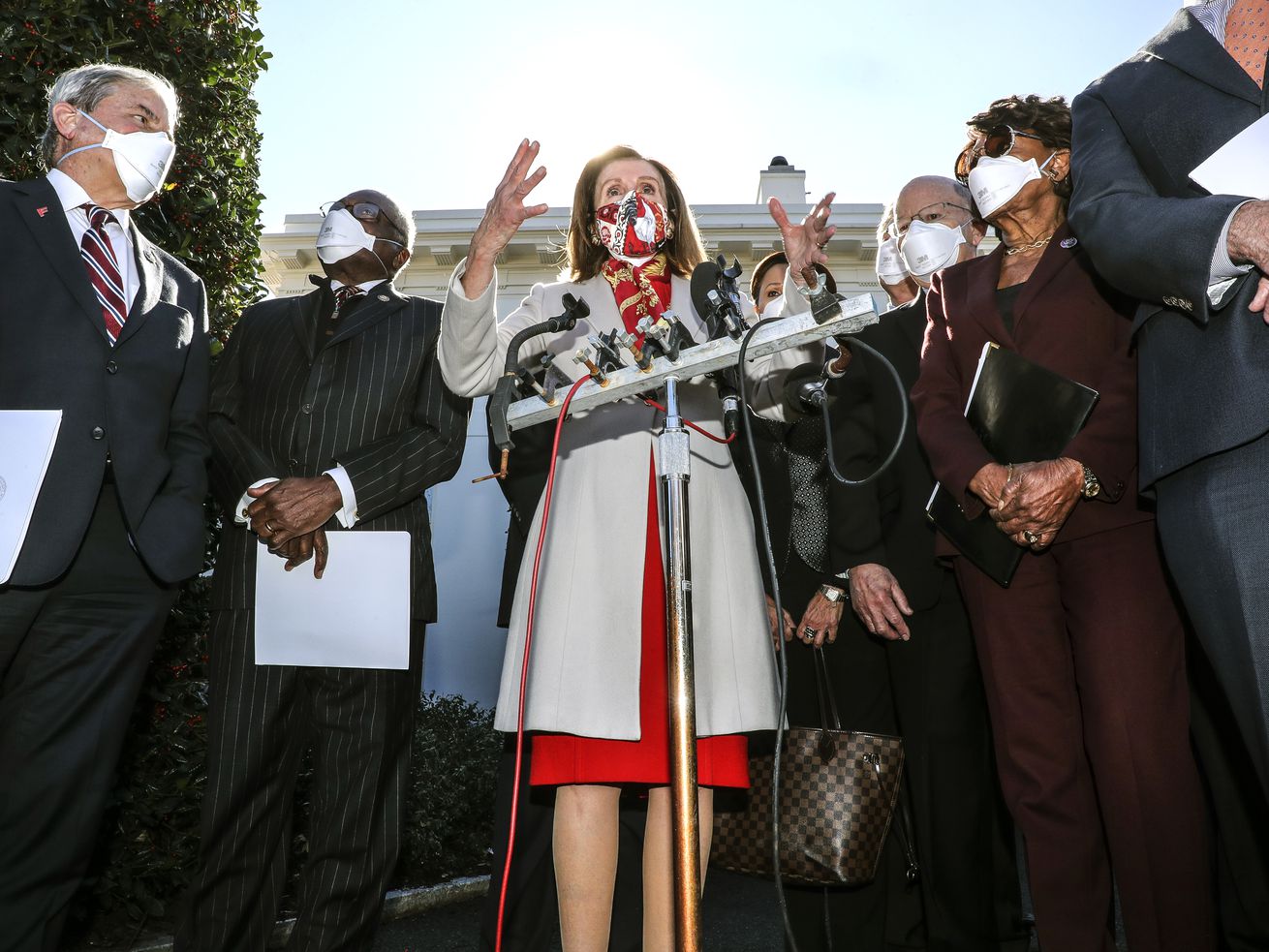

Democrats in Congress appear to recognize this problem. They plan to include some expansion of Medicare — by adding new benefits and perhaps making more people eligible — in the major budget reconciliation bill they hope to pass in the coming months.

For now, they appear to be focused on adding new dental, vision, and hearing benefits. They are working with finite resources; money spent on new benefits is money that can’t be spent on adding more people to the rolls or lowering patients’ out-of-pocket costs for other medical services.

Medicare is not, as it exists right now, comprehensive coverage for all of its beneficiaries. But improvements to the program risk antagonizing a private insurance industry that enjoys a large and growing business filling in the gaps of the traditional Medicare program. (It also remains to be seen whether Democrats can pass provisions targeting Medicare drug prices, ardently opposed by drug manufacturers, as part of the reconciliation bill.)

Polls show that Medicare expansion, of many types, is popular with voters. Granting new dental, hearing, and/or vision benefits to the 60 million people who rely on Medicare could be a political winner for Democrats. That’s one reason the Biden White House is reportedly trying to figure out how to get benefits to seniors as soon as possible, even though the draft bill released by House Democrats would not start new dental benefits until 2028.

But that means Medicare’s traditional benefits may be left untouched. Patients will still be forced to navigate a complex web of Medigap or Medicare Advantage plans to supplement the traditional program, or else risk thousands of dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Currently, an estimated 6 million Medicare beneficiaries do not have any supplemental or alternative coverage, meaning they in theory have no cap on their out-of-pocket costs if they require a lot of medical services.

Democrats in Congress could create new benefits, improve the benefits that already exist, or make more people eligible for Medicare — but they don’t appear prepared to do all three. Millions of Americans could pay a price for the holes left in the program.

Where Medicare falls short

Lee White of Utah estimates he paid $30,000 in health care bills last year, even though both he and his wife are enrolled in Medicare.

According to White, about $10,000 of that was spent on medical care that is technically covered by Medicare. There are the visits to primary care doctors and specialists; his wife, Marilyn, has had multiple sclerosis since the 1980s, so they are at the doctor’s office a lot. She broke her leg in a fall recently, which put her in the hospital. There is also imaging and prescription drugs, for which the Whites have to pay their share.

Medicare Part A and Part B, which provide inpatient and outpatient benefits, require patients to pay coinsurance, a percentage of the total cost of a service. There is currently no limit on how much a beneficiary could be asked to pay, unless they have supplemental coverage.

Part D plans for medications usually do have a cap, but there is still a deductible that patients must meet. There has also been a gap in coverage called “the donut hole,” which temporarily leaves patients with large prescription drug bills to cover.

Some patients also pay premiums. Low-income people eligible for Medicaid have all of their costs covered by that program.

Then there are the home health aides who care for Marilyn, which Medicare doesn’t cover at all. White says that’s $25,000 or more every year.

Most Americans don’t have any long-term care insurance, and the government typically doesn’t provide it unless your income and assets are low enough to qualify for Medicaid. Medicare’s long-term care benefits, as currently structured, are extremely limited and do not include the kind of nonmedical assistance that patients like Marilyn rely on to stay in their home.

White, who worked for years in public policy at the AARP, says he and his wife are fortunate to be able to afford her home care on their own, partly thanks to the health benefits White receives from his old job in retirement.

It’s important to White that Marilyn be able to stay home. It’s the place they gather with their family, where they encourage their grandchildren to run wild. He also knows, off the top of his head, what the life expectancy is when somebody enters a nursing home: two years.

White pays to have aides come five days a week, four hours a day, to help with bathing, meal preparation, and housekeeping. Those are services Medicare won’t cover, but they are essential for the Whites’ way of life: Lee himself has a neurological condition that makes it more difficult for him to help his wife move around the house. He worries about dropping her and causing another broken leg, or worse, a hip.

But the cost of paying for that in-home help is still a strain.

“It’s very, very dicey,” White says. Medicare “doesn’t cover the kind of things we need.”

Medicare has been patched together over the decades, and its benefits reflect that fractured history. It started as hospital insurance, reflecting health insurance as it largely existed when the program was created in 1965. It wasn’t until 2003 that Medicare covered prescription drugs. Congress has fitfully tried to improve its cost-sharing for patients, sometimes (such as in the ’80s) passing a new benefit and then rolling it back.

When the Affordable Care Act was passed in 2010, Congress put a cap on out-of-pocket costs for private health insurance plans sold under the law. But Medicare, created in an earlier era of health coverage, has no such cap. It stands out, among all the various kinds of health insurance in the US, as an example of outdated policy.

“Medicare is one of the few health plans or programs out there today that doesn’t have a limit on out-of-pocket spending,” Tricia Neuman, senior vice president at the Kaiser Family Foundation, a health policy nonprofit, told me.

The traditional program has never covered dental or vision benefits either. And the statistics on US seniors’ dental care are especially atrocious as a result.

About half of Medicare’s 60 million beneficiaries have no dental coverage at all. The other half purchase some kind of private insurance.

Those without coverage either pay for dental care entirely on their own, or they don’t get any at all. The data shows many of them fall in the latter group: More than half of Medicare beneficiaries have not seen a dentist in the last 12 months, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation. Those people were disproportionately Black, Hispanic, and low-income.

“Dental coverage is truly an equity issue,” Neuman said, “because there’s such disparities in use of dental services along racial and income lines.”

The links between dental health and other physical health have become much better understood in the years since Medicare was established. But dental care remains out of the scope of the traditional program for now, as are vision and hearing benefits.

What are Democrats willing to do?

Democrats say they want to expand Medicare — but they also have to be mindful of the influential health care lobby and the fiscal concerns of the party’s more moderate members. Intense opposition from the industry would pose a political challenge to the upcoming reconciliation bill, which will need to get every Democrat onboard in the Senate, and has just a small margin for error in the House.

Private health insurers are invested in the Medicare program as it exists now. Medicare Advantage, formally established (under a different name) in the Clinton administration, has slowly supplanted more and more of the traditional program.

Medicare Advantage plans are sold by private companies as an alternative to traditional Medicare. They tend to resemble commercial insurance, with a deductible and an out-of-pocket cap. Most of these plans also provide some of the dental, vision, or hearing benefits that the traditional program doesn’t.

Seniors have gravitated to the private plans in part because they are more seamless than traditional Medicare. Enrollment has grown from 12 million in 2011 to about 26 million in 2021. Medicare Advantage now accounts for 42 percent of enrollment, up from 25 percent a decade ago.

Otherwise, Medicare beneficiaries who stay with the traditional program sometimes buy supplemental insurance to cover some of their cost-sharing or benefits that aren’t included. About one in four traditional Medicare enrollees buys a so-called Medigap plan, which makes that another lucrative secondary market for insurers.

Improving traditional Medicare’s benefits — by introducing new vision and dental benefits or by lowering patients’ cost-sharing — threatens health insurers’ interests.

It’s also going to cost money, and one way to pay for these new benefits would be to cut payments to providers or impose new taxes on private insurance plans. But that is also sure to draw opposition.

The health insurance industry “seem[s] worried about the reduced differentiation in benefits between Medicare Advantage and [traditional Medicare] and being forced to pay for the extra benefits more than anything else,” one lobbyist who works with health insurers told me.

The Democratic majorities are walking a tightrope no matter what they decide to do with Medicare. Hospitals and doctors are also likely to object if Congress tries to expand the program to people younger than 65, because Medicare pays providers less money than the commercial plans many of those people would otherwise be enrolled in.

Democrats in Congress have put forward a wide variety of Medicare expansion proposals, everything from new vision and dental benefits to lowering the age of eligibility to 60 to making everyone eligible for its benefits. For the upcoming reconciliation bill, it seem the top contenders are new dental, vision and hearing benefits, according to media reports, with senators on the left also pushing for making more people eligible. Improving the program’s traditional benefits or adding long-term care coverage does not seem to be on the table, though President Biden does want to spend more money on Medicaid’s home-based services benefits.

Every policy choice comes with a trade-off. Democrats in theory have at least three options: adding new benefits, expanding eligibility, and improving traditional coverage. The debate over the next few months will determine what the next expansion of Medicare looks like — and which holes in the program will remain.

Author: Dylan Scott

Read More