The ballot will have two US Senate races, one with party labels and one without them. The latter could help the Democratic candidate.

Democrats looking to snag another US Senate seat from the South are hoping for a replay of the 2017 Alabama special election that sent Doug Jones to Washington. A particular wrinkle in Mississippi’s election laws — a provision for special elections without party labels — makes this outcome somewhat more likely, even if still a long shot.

When Mississippi voters go to the polls this fall they will be choosing their entire delegation to the US Senate. Sen. Roger Wicker (R) is up for his regularly scheduled reelection bid, and there will be a special election to replace Thad Cochran (R), who retired earlier this year. Mississippi is a deep-red state that voted for Donald Trump by a comfortable 17-point margin in 2016. In a typical election, this would be an easy seat for the GOP to hold.

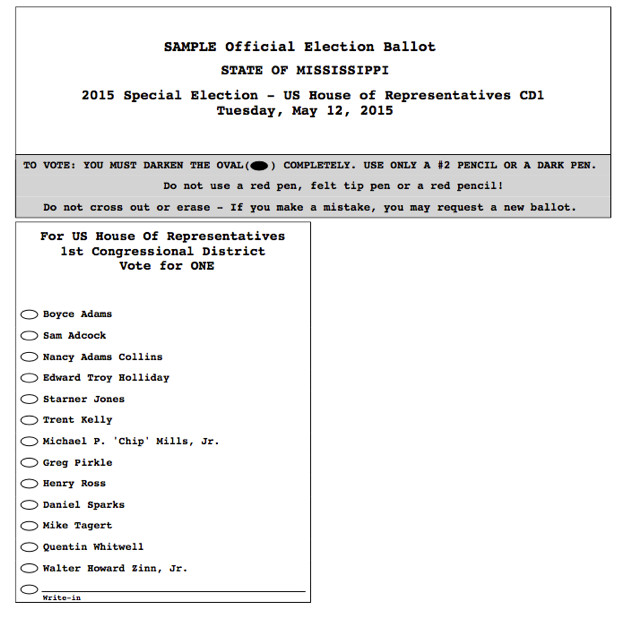

However, special elections in Mississippi are conducted without partisan labels. Therefore, even though the candidates will campaign as Democrats or Republicans, they will not be identified as such on the ballot. My research has shown that this ballot design can dampen voter participation and possibly scramble partisan behavior, adding a layer of uncertainty to the process.

The image below shows what a Mississippi special election ballot looks like. It is a sample ballot from a 2015 congressional special election to replace the late Rep. Alan Nunnelee in Alabama’s first district. There were 13 candidates, but no party labels, on the ballot. Democrat Walter Howard Zinn Jr. won the primary race, with Republican Trent Kelly finishing second. Kelly then handily won the run-off with approximately 70 percent of the vote, as to be expected in the heavily Republican district.

Having a ballot without party labels for a seemingly partisan election is unusual, but it has a long history in the American South. Near the turn of the 20thcentury, the American states rapidly adopted the practice of conducting elections with the “Australian ballot,” or the secret ballot as we currently know it today. The Australian ballot had three major components: It was issued by a government agency (instead of the parties), it was filled out in secret, and it identified candidates by their party affiliation.

Five Southern states did not fully implement the Australian ballot since they chose not to identify candidates by party. In a 1917 dissertation on the history of Australian ballot, Elden Cobb Evans wrote that Florida, Maryland, Mississippi, Tennessee, and Virginia omitted party labels “to get rid of the negro vote.” There was a high share of illiterate voters at this point (both African American and white). The Democratic Party, which enjoyed one-party rule in the South during this era, designed ballots so that the Democratic candidate could always be listed first. Therefore, illiterate voters could be instructed to just vote for the top candidate, helping secure the vote for Democrats and suppress the African-American vote.

These states mostly added party labels over time. In an article in State Politics and Policy Quarterly, I examine what happened when Virginia added party labels to their special elections in 2000. The nonpartisan ballot, protected by the Harry Byrd machine for decades, had helped Democrats muddy the waters during the period of realignment when Southern conservatives went from voting for Democrats to Republicans. These voters had been electing Republicans at the presidential level since Richard Nixon in 1968, but continued to elect Democrats at the state level. After Republicans took control of the Virginia state legislature in the 1990s, they decided to add the party labels to the ballots under the belief it would help them accelerate and solidify their gains.

It worked. When ballot labels were applied in Virginia in 2000 Republicans strengthened their hold over House of Delegates and State Senate. Two important shifts happened in Virginia with the introduction of the partisan ballot:

- First, voters became more likely to actually vote in all of the elections in Virginia. Specifically, there was about 15 percent less “roll-off” in which a voter would vote for the highest office on the ballot, such as governor, but not for lower offices like the Virginia House of Delegates.

- Second, party labels made state-level voting in Virginia more like a national election. In technical terms, the vote shares of Republicans in the House of Delegates in 2001 became more like the pattern of support for George W. Bush in the 2000 general election, even while Democrat Mark Warner won the governor’s race.

The lessons for Mississippi are potentially consequential. The special election could see lower participation, even with a partisan election occurring on the same ballot. And the lack of party labels could unmoor at least some voters from their national partisan position in either the top-two primary or the run-off.

Neither of these effects is likely to swing the special election on its own. However, an added dose of uncertainty is unlikely to help Republicans looking to hold the seat. Moderate Mississippi voters may well be left with a similar choice to what happened in Alabama, with a hardline conservative Republican running against a centrist and well-qualified Democrat. In Alabama, an energized opposition took advantage of a late-breaking scandal (Moore’s sordid sexual history), an unenthusiastic Republican electorate, and Trump’s lagging approval ratings to win the seat. In Mississippi, the lack of party labels could be a minor factor with major implications.

Alex Garlick is an assistant professor of political science at the College of New Jersey.

Read More

https://cdn.vox-cdn.com/community_logos/52517/voxv.png