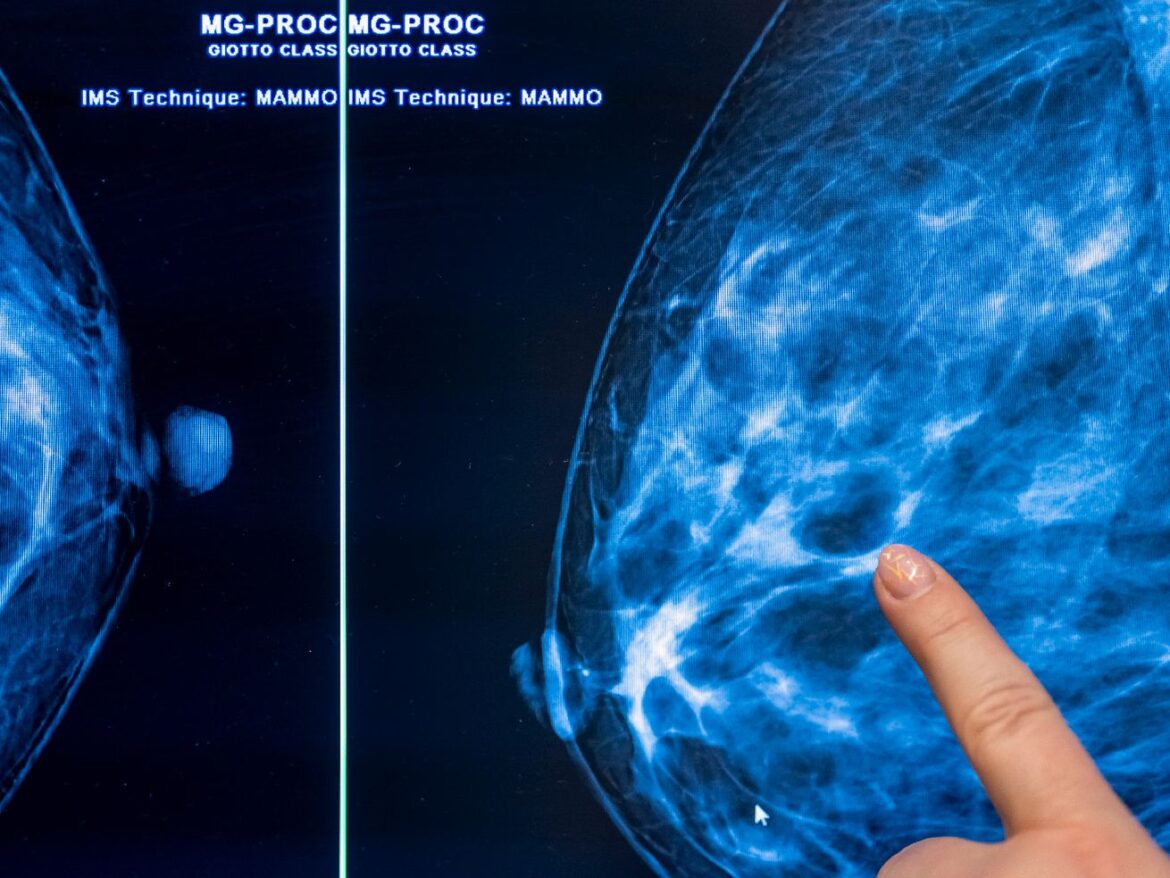

The new breast cancer screening recommendations for women over 40 are surprisingly fraught.

On May 9, the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) released a draft of their new guidelines on who should be screened for breast cancer. The biggest change: recommending that women with average breast cancer risk start getting mammograms every two years beginning at 40, instead of starting at age 50.

According to the recommendation’s authors, the reasons for the change included a noticeable increase in breast cancer cases among women in their 40s between 2015 and 2019, as well as a higher likelihood of late cancer diagnoses — and of dying due to breast cancer — among Black women in particular.

“The most important thing for women to know is to begin screening at the age of 40, because it just might save your life,” said USPSTF chair Carol Mangione in a video on the USPSTF website.

But a number of experts say it’s not that simple. For a test so often touted as lifesaving, there’s a surprising lack of consensus about how much mammography actually prolongs lives, and whether the unnecessary medical care mammograms sometimes lead to is worth their benefits.

Breast cancer causes more than 42,000 deaths in the US each year, and about 40 percent more Black women die due to breast cancer than do white women. The causes of this disparity are complex — and recommending more mammograms to all Americans as the solution comes with increased physical, emotional, and economic costs.

Will they be worth it? Let’s get realistic about what these recommendations can and can’t do.

The new recommendations can increase rates of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment — which is both good and bad

The USPSTF’s recommendations offer guidance on how to use mammograms for screening average-risk people. That’s worth keeping in mind for a couple of reasons. First, higher-risk people — like those with family histories of breast cancer — may need to be screened differently.

Additionally, not every mammogram that gets done is for screening: These recommendations do not apply to, for example, someone who detects a lump in their breast. (In that scenario, because the person has a symptom before they get the test, the mammogram is a diagnostic test — and the procedure and what follows are a little different.)

When screening tests work, they find medical problems early, before people have any indication that they might have that problem. Mammograms can do this, flagging tiny changes associated with many types of breast cancer. Some breast cancers are slow-moving while others grow quickly; some are treatment-responsive and others are resistant to treatment; some readily invade other tissues and others resolve on their own. Mammograms can help spot them all.

But they can also detect lots of breast changes that aren’t actually abnormal, like benign texture differences in the breast tissue called fibrocystic changes. Trouble is, they’re not great at distinguishing what’s harmful from what’s benign. For that reason, abnormal mammograms are generally followed by a cascade of other evaluations to help determine what’s going on, depending on what they’ve found.

Increasing the number of mammograms people get can increase the number of abnormalities that get diagnosed and will lead to more follow-up ultrasounds, biopsies, and other procedures. It can also increase the number of people getting treated for conditions judged to be cancerous, with a range of surgeries, chemotherapies, and radiation treatments.

But how much more premature breast cancer death can all this added care prevent? That’s not a simple question to answer.

The thing about breast cancer is that most types are so slow-moving and so responsive to therapy that even if people don’t get breast cancer treatment until they first notice a lump, they’re still highly likely to survive the cancer.

Yes, diagnosis in early stages of these cancers leads to better outcomes than late-stage diagnoses — but those early stages last a while, with the median time around 10 years altogether.

(About one in 10 breast cancers diagnosed in the US are very aggressive and resistant to treatment, and they usually move too quickly to be caught by a mammogram done only once every two years.)

That means that for people who are vigilant about changes in their bodies and have decent access to health care, the value-add of mammograms over simply being aware of your body is actually pretty small.

“The better we get able to treat a disease, the less important it becomes to find it,” said Gilbert Welch, a senior researcher at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston who studies cancer overdiagnosis. In other words, when we find treatments that work at many different stages of disease, the benefits of early diagnosis shrink dramatically. For breast cancer, that treatment is the anti-hormonal therapies that emerged in the 1990s and dramatically changed breast cancer survival rates.

A recent analysis by the Lown Institute, a nonprofit health care think tank, highlighted some key USPSTF figures, which show the limits of mammograms in a helpful way.

The analysis imagines a world without screening mammograms, in which women seek evaluation for breast cancer only when they notice a breast lump or other concerning symptoms. According to the USPSTF’s models, about 28 out of every 1,000 women in this world would die from breast cancer at some point in their lives.

Then, let’s look at what the previous guidelines — recommending regular mammograms starting at age 50 — can accomplish. If all women adhered to those guidelines, then seven of those breast cancer deaths would be prevented.

However, the USPSTF estimates those mammograms would also result in 1,021 false-positive mammograms and 148 biopsies that turn out to be benign. It would also lead to 10 cases of overdiagnosis — that is, treatment of a cancer that never would have harmed them to begin with.

That’s bad. False-positive mammograms are associated with psychological consequences, such as anxiety and sleep issues, that persist for years afterward. And the unnecessary surgeries, medications, and radiotherapies that follow breast cancer overdiagnosis cost the US an estimated $4 billion a year.

Now, what can we expect under the new guidelines, with the mammogram age starting at 40? The USPSTF projects that would save an additional two of those 1,000 women from a breast cancer death (technically, one and a half; the authors rounded up). But significant added harms would come with all of those extra positive mammograms: This scenario leads to an additional 62 benign biopsies and two additional overdiagnosed cases.

What all of this means is that the new recommendations can potentially lead to a lot of unnecessary, and potentially harmful, care. To some people, those trade-offs, even if they harm hundreds of people, are worth saving even one extra life.

What complicates things even further is that these are calculations set in the ideal world of a statistical model. The complexity of the real world leads to some changes in the math, especially for Black women.

The new recommendations can give Black women in particular an on-ramp to breast cancer care — but they can’t map the rest of the route

These models assume that every one of these 1,000 hypothetical women is equally watchful and attentive to changes in their bodies, and seek medical evaluation and care when they notice something’s off. They also assume that each has equal access to a medical system that provides the same quality of care to all of them.

But we know that latter part isn’t the American reality. Decades of economic and residential segregation mean Black Americans are more likely to be uninsured and to live in areas without readily available health care providers and facilities. Furthermore, the legacy of medical racism translates to high levels of distrust in medical providers among Black Americans. And Black women with breast cancer receive lower doses of breast cancer chemotherapy compared with white women.

As a result, even if Black women notice breast changes that may be associated with cancer, they may be less likely to seek and receive evaluation for those changes, and to get appropriate care when they do.

That delay means many Black women only start treatment in the later stages of disease, once the cancer is more likely to have spread beyond their breasts. These kinds of treatment differences explain, at least in part, why even Black women with treatable breast cancers have worse outcomes than do women of other racial and ethnic groups.

Black women also more often have the rarer, particularly aggressive triple-negative breast cancers, so named because their cells don’t carry any of the three targets at which the most effective treatments take aim. These cancers, which make up around 20 percent of all US breast cancers and have lower survival rates than other types, are at least twice as likely to be diagnosed in Black women than in white women, especially at younger ages.

The role of mammograms in improving these cancers’ outcomes is unclear: Triple-negative breast cancers are generally harder to see and progress far more quickly than other cancer types, making them hard to catch at early stages by a test done only every one or two years. Although magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is better at diagnosing these cancers, its cost and resource demands are barriers to using it as a population-wide screening tool.

The more common and more treatable breast cancers are where the new recommendations could potentially help by giving Black women an on-ramp to earlier cancer care. In this sense, regularly scheduled mammograms — which are covered by all US insurance plans and are often available free for uninsured people — could make an end-run around some of the many reasons women might let a breast lump go unevaluated for years.

Because routine mammograms could help improve access to care among Black women with treatable cancers who’d otherwise lack a treatment entry point, this group could have more to gain than lose from getting more mammograms. In USPSTF’s models, the number of Black women’s lives saved by routine mammograms was slightly higher than in the general population, no matter at what age they started.

What the recommendations don’t (and can’t) do is plot out a route for after the on-ramp.

More mammograms aren’t the solution to the biggest problems in breast cancer

The USPSTF didn’t restrict its new recommendations to Black women alone: It recommended it for all women. That also means more mammograms for women who have already effectively maxed out the benefit they could get from the screening test. In that group, the recommendation will likely lead to more benign biopsies, more overdiagnoses, and more harm.

Some researchers have suggested starting screening mammograms at different ages in different racial and ethnic groups based on these considerations. However, the USPSTF opted not to do that.

USPSTF member and internist John Wong told Vox in an email that rising rates of breast cancer among younger women of all racial and ethnic backgrounds provoked the choice. Younger women stand to have more years of life saved when a mammogram diagnoses a breast cancer in them than in an older person, he said. “Fundamentally, with more women being diagnosed at younger ages, each life that is saved from dying of breast cancer means even more years that women have to live after a diagnosis,” he said.

That’s true — if the early diagnosis is what saved their life. But it’s possible these younger women would’ve survived the same duration even with a later diagnosis.

Shannon Brownlee, a special adviser to Lown’s president, said the new recommendations mean “exposing a large population of women to overdiagnosis and overtreatment — which is harmful, we know that — in order to fix the fact that poor women and Black women have poor access to health care.”

Furthermore, they don’t actually fix the health care access disparities at the root of the problem, she said, because they do nothing to address barriers to getting timely care for cancers identified during those screenings.

“Maybe it’ll help some women who really didn’t have access” to health care, she said, “but they still don’t have access: You can get your mammogram now for free, but then you can’t get treated because your insurance isn’t adequate.”

It “just seems like a really dumb way to fix that problem,” she said. “This is really a travesty. Frankly, I think it’s going to harm a lot of women.”

Instead of increasing the number of mammograms, it would be far more beneficial to research and identify the environmental, genetic, and other potential causes of triple-negative breast cancers that create added risk for Black women, said Brownlee.

Also critical, she said, is addressing racial inequities in health care access.

Many studies have documented how differences in environment, insurance coverage, and treatment likely contribute to breast cancer mortality inequities and also drive Black Americans’ dramatically worse mortality more broadly. Fixing these inequities is generationally important work that urgently demands the attention of American policymakers, scholars, and health care institutions.

But more mammograms won’t solve these problems, said Welch. “You can’t screen your way out of health disparities.”

What’s a person with breasts to do?

The new recommendations are still just in draft form and will be open for public comment through June 5. But things might not get much clearer even once they’re finalized. Meanwhile, what’s a woman with average breast-cancer risk to do?

Welch urges viewing the recommendations in a bigger context. “No one should think this is the most important thing they do for their health,” he said. Instead, people should do “what their grandmother would have told them 40 years ago: Eat your fruits and vegetables, go play outside, run around, find things that give your life meaning, exercise.” he said. “And don’t smoke. Whatever you do, don’t smoke.”

Even if you opt out of mammograms, being aware of your body and seeking care for early warning signs and for other general preventive care makes sense. (The USPSTF officially recommended against breast self-exams in 2009, but some research suggests the practice still has value, especially in high-risk groups, like those with personal or family breast cancer histories or who carry certain genetic mutations.)

It’s understandable if, even knowing all of this, some people still want regular screening mammograms. If he had to write the mammography guidelines, Welch would tell people that getting a mammogram is a choice. Although women who notice a breast lump should seek care immediately, viewing their breasts as ticking time bombs can itself create a sense of unwellness, he said.

“You develop a new problem, come see the doctor,” said Welch. “But this whole question of to what extent you should see your body as a laboratory, you need to be testing it every other day — I think that’s a recipe for a sick society.”