The Upper East Side gets bloody in Virginia Feito’s vicious, gorgeous thriller.

Early on in Mrs. March, the moody new literary thriller by Virginia Feito that’s been optioned for the screen by Elisabeth Moss, we get a telling detail about our eponymous heroine.

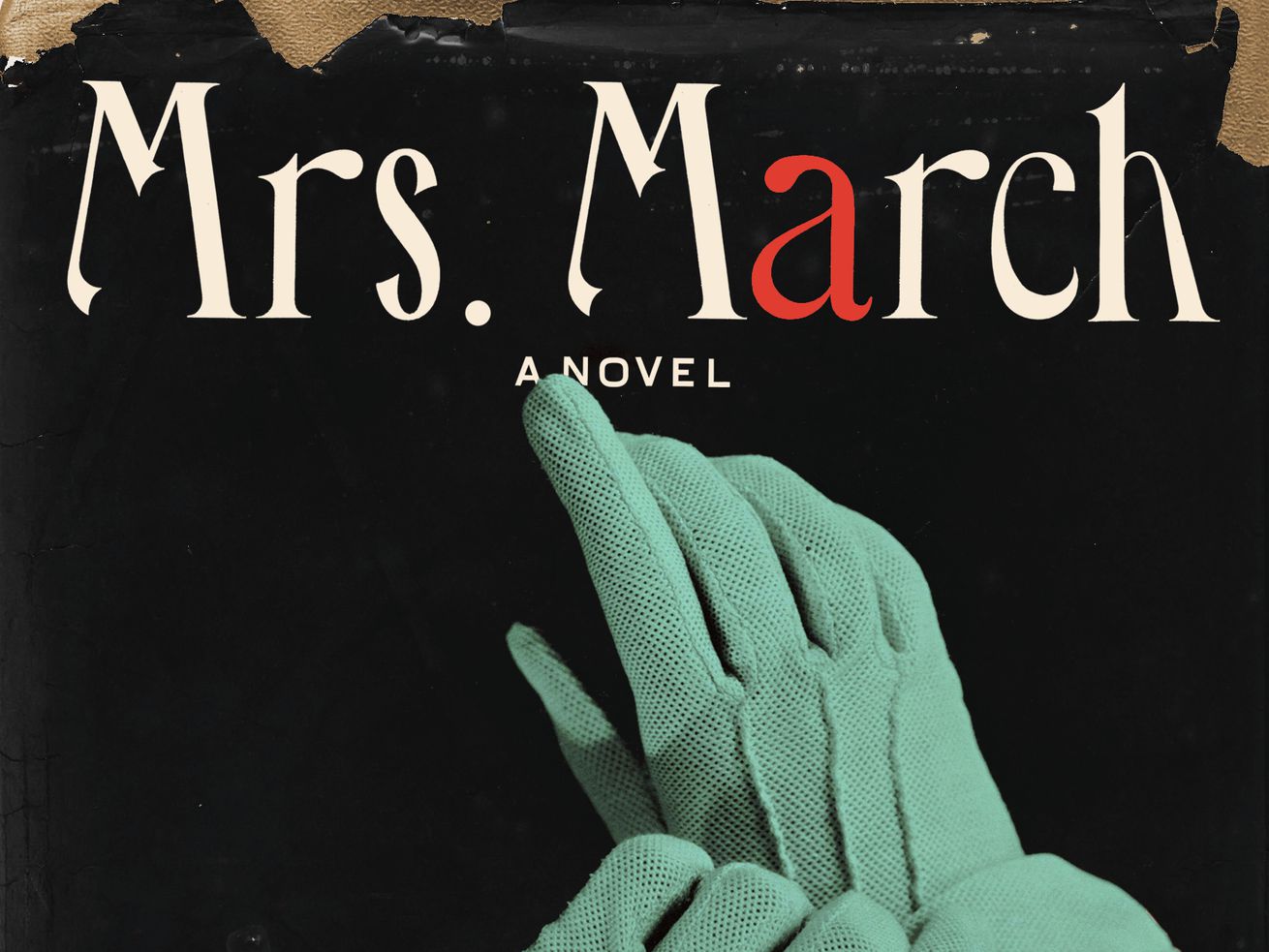

Upper East Side housewife Mrs. March, we learn, wears mint green kidskin gloves. What’s more, she considers these gloves to be remarkably daring. They were a Christmas present from her husband, George, and Mrs. March loves them.

“She would never have picked that color out, not once believing she could pull such a thing off,” Feito writes, “but she thrilled at the fantasy that strangers, when they saw her wearing them, would assume her to be the kind of carefree, confident woman who would have selected such a bold color for herself.”

Crammed into this compact little anecdote is a whole plethora of information about Mrs. March. Like the nameless Mrs. de Winter in fellow thriller Rebecca, Mrs. March has a drab, self-effacing personality, so much so that she doesn’t even rate a first name. She is, moreover, shamefully aware that strangers find her drab, and longs to be exciting, charismatic, effortlessly charming. So askew is her frame of reference for excitement and danger that she believes mint green gloves might be a meaningful step toward glamour.

Mrs. March finds herself to be in special need of glamour, because as the novel opens, she is in the act of learning something humiliating. Her novelist husband has based the protagonist of his latest novel on her. Mrs. March is captured unmistakably: her mannerisms, her appearance, her habit of wearing gloves at all times. But the comparison is not flattering.

The protagonist of George’s novel is a prostitute whom no one wants to sleep with. She’s covered in sores and foul smells, and her few clients pay her out of pity and decline to touch her. Her name is the title of George’s book: Johanna. (Even the book-within-a-book character gets a first name! But Mrs. March doesn’t.)

What ensues from this revelation is a little bit Hitchcock, a little bit Patricia Highsmith, a little bit “The Yellow Wallpaper.” Feito’s cool, elegantly mannered prose seems to place us sometime in the midcentury, the era of icy, repressed housewives goings genteelly mad, and Mrs. March does not disappoint. She is enraged by George’s treatment of her, and has no apparent understanding of how to process that rage.

Mrs. March begins to imagine that every person she knows and every stranger on the street must have read George’s book, must be privy to her shame. She begins to suspect that George might be behind a mysterious murder in Maine. She begins, also, to see doppelgängers — of herself, of George, of the murdered girl — crawling through her tasteful apartment, to see its walls covered in dead vermin.

Her narration seems to gradually unravel, to become less and less reliable as we read. All that’s clear is that she’s leading us, inexorably and without quite seeming to know why, toward something bloody.

Mrs. March is a sneakily brutal book, a scream almost drowned out by a whisper. Feito begins the story with needle-sharp stabs at Mrs. March’s simultaneous snobbery and self-consciousness, so brief and so pointed as to simply be funny. In the first 10 pages alone, Mrs. March fails to confront a woman who cuts in line in front of her, tells a waiter she’s waiting for a nonexistent friend so as not to be called out for dining alone, and recalls early dates with George, when she didn’t want to “jinx” anything “with her personality.” She’s such a doormat that you’re inclined to mock her rather than sympathize with her — but as Feito builds to her climax, and Mrs. March begins to fall apart, you begin to wonder if all those early pinpricks weren’t aimed at you all along.

If there’s a major flaw here, it’s that Mrs. March seems if anything too clearly meant to end up onscreen. Mrs. March’s interiority is rendered almost exclusively in hallucinations and dark images, pre-translated for a visual medium. Her mannerisms and foibles are simply crying out to be portrayed by an actress over 40 looking to pick up an Emmy on a prestigious cable miniseries. (Elisabeth Moss already called dibs, but I’d love to see what Cate Blanchett could do here.) Feito’s prose never falters, but she also doesn’t seem inclined to take advantage of the artistic possibilities the novel can offer that television can’t: psychology expressed through text rather than images, for instance.

Still, there’s a relentless build to this book, a gnawing dread that sets in early and never quite lets up. And between Feito’s silver-polish sentences and her eerie psychological acumen, you don’t want it to. Instead, you read Mrs. March the way Mrs. March imagines everyone around her reading Johanna: avidly, until you come to know its heroine with a terrible, unbreakable intimacy.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More