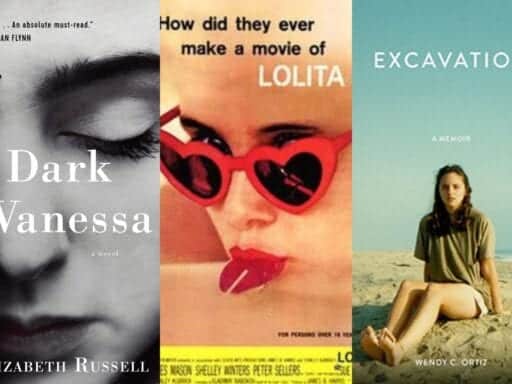

In My Dark Vanessa and in Excavation, two young girls read Lolita as a love story.

At the end of January, while publishing was still convulsing in the throes of the American Dirt scandal, a new literary controversy emerged that threatened to surpass American Dirt entirely: the story of a major new forthcoming novel, My Dark Vanessa.

And at first glance, American Dirt and My Dark Vanessa appeared to share some essential DNA. American Dirt is a thriller about a woman and her young son fleeing Mexico for the US, and its author Jeanine Cummins received a seven-figure advance and massive early publicity, including a blurb from Stephen King. But when American Dirt came out in January, Chicanx readers heavily criticized Cummins for her use of offensive tropes and clichés, noting pointedly that Cummins is not of Mexican descent. (Cummins has identified at times as a white woman and at times as Latina; she has a Puerto Rican grandmother.)

Meanwhile, authors of color rarely receive the kind of lavish advance or institutional support that American Dirt did. So for many observers, the amount of money and resources publishing had poured into American Dirt showed that the industry is only willing to reward the stories of brown people when they are told by white people, and when they play into white people’s pre-existing and inaccurate ideas. And My Dark Vanessa would shortly afterward find itself caught in the same narrative.

My Dark Vanessa also received a seven-figure advance and massive early publicity, including a blurb from Stephen King. Its author, Kate Elizabeth Russell, is white. So when the Latina author Wendy C. Ortiz noted, first on Twitter and then in an essay in Gay Mag, that there were “eerie similarities” between her own 2014 memoir Excavation and Russell’s My Dark Vanessa, onlookers were quick to jump on the parallels.

Both Excavation and My Dark Vanessa are stories about teenage girls in sexual relationships with their older male teachers. But while Excavation is a memoir and a true story, My Dark Vanessa is a novel that opens with an author’s note urging readers not to take it as “the secret history” of its author’s life. That meant, some on literary Twitter concluded, that My Dark Vanessa was, like American Dirt before it, just another case of a white woman telling a brown woman’s story for her, and getting handsomely rewarded for it.

The broad strokes of Ortiz’s actual argument were more nuanced. Excavation was rejected by major publishers as unsaleable and ended up at a small press, shut out from consideration for major awards or review coverage at major outlets. But publishers seemed to consider My Dark Vanessa — a similar story, but fictionalized and told by a white woman — to be very saleable, and they had given it the kind of publicity outpouring that would make it inescapable. What was the difference between these two books, Ortiz demanded, if not her own race, and the problem it presented for an industry like publishing that is 84 percent white?

But Ortiz also criticized Russell for telling the story of a student-teacher relationship in a commercial novel, “fictionalized, sensationalized,” and for not reaching out to Ortiz herself until she could only offer “an awful lot of justifications, a little too late.” And so the My Dark Vanessa controversy briefly became a scandal about appropriation and plagiarism.

Russell was swamped with outraged readers accusing her of stealing Ortiz’s story and trying to profit from it. Oprah, who reportedly was close to announcing My Dark Vanessa for her book club and who had just faced immense backlash for endorsing American Dirt, backed out. Russell deleted her Twitter account.

The thing was, Russell hadn’t actually plagiarized Ortiz’s story. Within a few days of Ortiz’s essay publishing in Gay Mag, Russell had posted a new note on her website explaining that My Dark Vanessa was based on her own experiences as a teenager.

“The decision whether or not to come forward should always be a personal choice,” Russell wrote. “I have been afraid that opening up further about my past would invite inquiry that could be retraumatizing, and my publisher tried to protect my boundaries by including a reminder to readers that the novel is fiction.”

And so while the American Dirt controversy evolved into a political-literary movement with action plans and campaigns, the My Dark Vanessa controversy has ebbed into an embarrassed sense of puzzlement that seems to surround everyone involved. It’s a messy situation without any of the clear villains or outrageous barbed wire manicures that American Dirt had.

Certainly it was a shame that publishing had lifted up the white lady’s book and ignored the book of the Latina woman, people seem to agree. But also, surely we shouldn’t be out here forcing victims of sexual abuse to tell us exactly what happened to them before we let them write novels based on their experiences? Surely.

What is at stake in the My Dark Vanessa controversy is the systemic and monolithic whiteness of publishing, and the way it shapes whose stories we value and whose we push to the side. But ironically, that’s the same question that is at stake in both My Dark Vanessa itself and in Excavation.

I recently read Excavation and My Dark Vanessa (which comes out March 10) back to back. It was an odd experience. The two books aren’t particularly similar in their styles or their aims, but their shared subject matter means they keep pivoting around the same tropes. The teacher admiring the teenage girl’s writing, telling her that she’s special, that she’s ageless, that he has a crush on her, that she has power over him. The teenage girl, flattered and thrilled and obscurely shamed, falling in response ever more under the teacher’s power. These moments repeat and repeat in both books, because they are how grooming works.

What is most striking about both Excavation and My Dark Vanessa, though, is the way they both put those moments in conversation with our culture’s canonical story of pedophilia and child sexual abuse: Lolita. Both Excavation and My Dark Vanessa engage furiously with Lolita — and they are both overwhelmingly preoccupied with whose stories we value when we read Lolita, and whose we ignore. Which, in the end, is the question publishing is trying to answer about itself right now.

My Dark Vanessa is a tale of abuse that mirrors Lolita. But many see Lolita as a dark love story.

Lolita, written by Vladimir Nabokov and published in 1955, is the story of a man named Humbert Humbert who kidnaps and repeatedly rapes his stepdaughter, Dolores, whom he calls Lolita. Humbert Humbert — the archetypal unreliable narrator — narrates the book in panting, leering, lyrical prose, so that when you read Lolita, you find yourself trapped inside his head, ogling a 12-year-old girl along with him.

You watch as Humbert Humbert grooms his target. First he flirts with Dolores, who cherishes a schoolgirl crush on her new stepfather. Then he escalates to plying her with pills and stealing kisses.

Eventually, after her mother has died, he isolates her. Dolores is away at camp at the time, and Humbert shows up unexpectedly to sign her out and drive her off on a never-ending road trip. That’s when he sleeps with her.

“It was she who seduced me,” unreliable Humbert tells us, and it’s true that in the account Humbert gives us, it is Dolores — groomed by Humbert and with a child’s ignorance of sexual boundaries — who actually initiates sex. But there’s plenty of evidence within the text that Lolita, aged 12, is not prepared for what happens next, and nor does she enjoy it.

Humbert imagines painting the scene of the consummation in ecstatic fragments, but the fragments resolve themself into a single and tragic image: “There would have been poplars, apples, a suburban Sunday,” he says. “There would have been a fire opal dissolving within a ripple-ringed pool, a last throb, a last dab of color, stinging red, smarting pink, a sigh, a wincing child.” The wincing child is Dolores, and the last dab of color is her blood.

The next day, Dolores is angry with Humbert. “You chump,” she tells him. “I ought to call the police and tell them you raped me. Oh, you dirty, dirty old man.” That’s when Humbert tells her that her mother is dead. After that, “we made it up very gently,” Humbert tells us. “You see, she had absolutely nowhere else to go.” Humbert has successfully isolated Dolores from any avenue of escape, and now he is the only person left to her who feels familiar. If she loses him, she has nothing. So she has to stay with him.

Lolita is a horrifying book, but it is also a beautiful book: the language is rapt and playful and gymnastic; it is a book that invites its reader to love it. And for many readers, particularly some male readers, it’s come to seem a little gauche to spend too much of your Lolita-reading time focusing on the idea that it is a book about the repeated rape of a child. After all, isn’t there some gray area here?

Writing for the New Yorker in 2012, Jay Caspian King described a professor who once told him never to forget that Lolita was a book about rape, and King’s feeling that this admonition ruined the novel for him. “My professor’s pronouncement felt too didactic, too political,” he writes, “and, although I tried to put it out of my mind and enjoy Lolita’s cunning, surprising games with language, I could no longer pick up the book without feeling the weight of his judgment.”

King is not the only person who objects to reading Lolita, which is explicitly a book about child rape, as a book about child rape. When Rebecca Solnit read Lolita as such in an essay on LitHub in 2015, she heard from so many angry men that she wrote a follow-up essay called “Men Explain Lolita to Me.”

“A nice liberal man came along and explained to me this book was actually an allegory as though I hadn’t thought of that yet,” Solnit writes. “It is, and it’s also a novel about a big old guy violating a spindly child over and over and over. Then she weeps.”

Because Lolita is a great novel, it’s able to hold ambiguities, to offer its readers multiple ways of engaging with its central story at once. In a way, Lolita contains three stories. There’s the apolitical story in which all that matters are the games with language and allegory and none of the characters are important. There’s the story told by Humbert Humbert, in which he is a powerless man at the mercy of the demonic nymphet Lolita, who seduces him. And there’s the story lurking beneath Humbert’s story, in which a child is groomed and then raped.

All three of these stories are present in Lolita. But it is still considered by many critics to be a little jejune to treat the third of Lolita’s plots — Lolita from the point of view of Dolores — as though it deserves equal billing with the rest of the book.

Like Solnit, I have often had men explain Lolita to me after I mention that the plot involves the repeated rape of a child. Here is a partial list of ways they have explained it:

“It was statutory rape, but it wasn’t rape-rape. She wanted it. It’s like he says, she’s the one who seduced him.”

“It’s naïve to read Lolita literally. It’s not about rape. It’s a book about language.”

“You don’t think Lolita is funny?”

“I feel so sorry for Humbert Humbert.”

“If she didn’t want it, she wouldn’t have stayed with him for as long as she did. She could have left.”

“Lolita is a love story.”

Reading Lolita as a love story gives Lolita all the power. Excavation and My Dark Vanessa both take issue with that reading.

The heroines of Excavation and My Dark Vanessa both read Lolita. In Excavation, 13-year-old Wendy asks for it for Christmas a few months after meeting her eighth-grade English teacher, Mr. Ivers. In My Dark Vanessa, 15-year-old Vanessa’s English teacher Mr. Straine gives her a copy, swearing her to secrecy about the source. Both Wendy and Vanessa, reading, understand themselves to be Lolitas, and both of them understand Lolita to be a love story.

Lolita is “about the young girl who wham-bams the older man, isn’t it?” Mr. Ivers asks when he sees Wendy reading the book in class. Wendy, who notes that she feels sorry for Humbert, asks Mr. Ivers what the word “folly” means, and he pretends she’s asking him about the word “fondle” instead.

By this point, Mr. Ivers has already told Wendy over the phone that he has “a huge crush” on her, and then initiated phone sex with her. And Wendy is receptive because although she feels neglected and out of control at home, Mr. Ivers makes her feel as though she has power over him. She describes “realizing the hold, the power I have over this person. … This is power in the curve of my hip, the way I turn to face him, the mystery of my turtleneck sweater.”

Later, reflecting on why she didn’t tell anyone, she thinks, “I felt responsible for his acts. … I was told I exuded sex and therefore I must be to blame.”

Lolita is the story “of a seemingly ordinary girl who is really a deadly demon in disguise and the man who loves her,” says Vanessa in My Dark Vanessa as she reads the novel for the first time. By now, Straine has begun to shower her with attention and told her that he wants to kiss her. Vanessa, who feels isolated at her boarding school where she has no real friends and considers Straine’s attention a lifeline, takes a clear meaning from his decision to give her the book: “What conclusion is there to draw besides the obvious?” she asks. “He is Humbert, and I am Dolores.”

It’s also clear to Vanessa that Humbert is the true victim of the novel. “If he were able to stop loving her, he would,” she thinks. “His life would be so much easier if he left her alone.” On those grounds, she comes to the conclusion that it’s her turn to step up to the plate and make a move on Straine: All she has to fear is rejection, but he’s looking at getting fired or worse if he chooses to escalate things himself. So she writes a slightly dirty poem and gives it to her English teacher, and he responds by kissing her.

Later in the novel, the now-adult Vanessa tells her therapist that she “tortured” Straine as a 15-year-old. “He was so in love with me, he used to sit in my chair after I left the classroom,” she says. “He’d put his face down on the table and try to breathe me in.”

As Lila Shapiro wrote for Vulture in February, “My Dark Vanessa can be read as a mirror image of Lolita,” with Vanessa taking over from Humbert as our unreliable narrator, telling us the story of a relationship she desperately wants us to believe is a love story. And this idea of Straine tortured by his lust for Vanessa is a detail right out of Nabokov. Humbert, too, is physically tortured by his lust for Dolores, so that after he kisses her eyelid early in their relationship, he tells us, “my heart seemed everywhere at once. Never in my life — not even when fondling my child-love in France — never — Night. Never have I experienced such agony.”

“Vanessa,” Vanessa’s therapist says in response, “you didn’t ask for that. You were just trying to go to school.”

Humbert Humbert renamed Dolores. Now we call her story with the name he gave her.

What’s at stake in the way we read Lolita is whose stories we choose to value: the story Humbert is telling us, in which he is a hapless lover utterly overwhelmed by the charms of Lolita the nymphet, and she has all the power — or the story underlying Humbert’s, in which a 12-year-old girl’s stepfather kidnaps and repeatedly rapes her, and he has all the power.

Vanessa and Wendy both believe in the first version of the story when they are children. Because that version of the story is so prevalent — because it is, in some ways, common knowledge — it’s easy for them to grasp. And it’s appealing, because it allows them to experience themselves as powerful, as in control of everything that has happened to them.

But as adults who are trying to heal, they turn to the second version of the story. They realize that it was their teachers who held the power — and used that power to groom and mold and change them.

“My own composition was changed when I met and was taught by this man,” writes Ortiz. “He seeped into my existence.”

“What could we have done? We were just girls,” one of Straine’s other victims tells Vanessa when they are both adults. And Vanessa thinks, “I know what she means — not that we were helpless by choice, but that the world forced us to be. Who would have believed us, who would have cared?”

Who would have believed them, when we all know that Lolita is a love story?

As a culture, we value Humbert Humbert’s story over Dolores’s. We also value the stories of white people over the stories of people of color.

My Dark Vanessa and Excavation are both mirrors of Lolita, inverted versions of Nabokov’s story that break Dolores out of her cage and ask her what she thinks about everything. But they are also mirrors of each other.

I heard about My Dark Vanessa for the first time in June 2019, nine months before it would eventually come out. I was at a publishing conference and Russell’s editor had been invited to present on the book, which attendees were told would surely be one of the most important books of its season. I made a note in my program that I should follow up and make sure I got a copy.

I never had to send that follow-up. In the months leading up to My Dark Vanessa’s publication, its publisher William Morrow sent me four copies: three galleys, and one finished hardcover. I put them all on my bookshelves to consider reading by January 28, when My Dark Vanessa was originally scheduled to come out, but then William Morrow’s publicist took me out to coffee.

“We’re moving it to March,” she explained, handing me a glossy catalog with the updated publication date listed. “It’s an IndieNext pick,” meaning that independent booksellers were going to name it one of the books that they would hand-sell to readers in March.

“Oh, okay,” I said, and updated my calendar on the spot.

I never had to work to find out about My Dark Vanessa or know when it would be coming out or to get my hands on a copy. The industry wanted me to know about it early, and I did. And I never had to wonder if people were going to be talking about My Dark Vanessa or if it was worth my developing an opinion on it as well, because I knew from the first moment I heard about it that it was a book people would be talking about. William Morrow was spending so much money on it that it couldn’t not be.

I heard about Excavation for the first time this January, six years after it came out, accidentally. I was researching the American Dirt scandal and came across Wendy Ortiz’s first tweets comparing My Dark Vanessa to Excavation.

I think this is going to be a thing, I told my editor. I’ll request a copy.

I looked up the name of the small press that put out Excavation: Future Tense. I had no preexisting relationship with Future Tense, so I looked up its publicist’s name and contact information, and wrote to her to ask her for a press copy.

After a week the publicist hadn’t responded. I wrote to her again. She never got back to me. In the end I bought a copy of Excavation myself, and sent the bill to Vox.

When Ortiz says the publishing industry didn’t treat her story the same way it treated Russell’s, she’s not lying.

So the My Dark Vanessa controversy ended up, in the end, expanding the idea that is at the center of the novel ever outward. We ignore the stories of young girls, the harm that is done to them, in favor of the stories told by the charming older men who prey on them, My Dark Vanessa tells us. And we ignore the stories of people of color, stories like Excavation, in favor of the stories told by white women, the controversy tells us. Both of those statements are true.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More