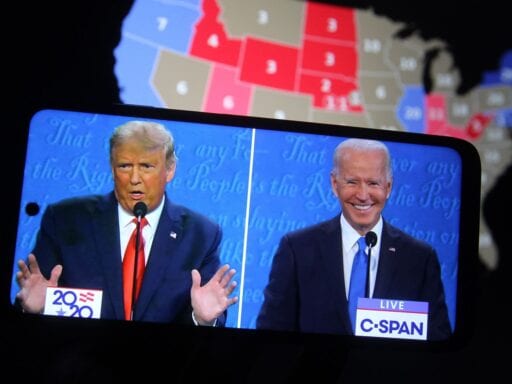

The FiveThirtyEight founder on polling error, Trump’s chances, and the possibility of an electoral crisis.

We are days away from the 2020 election, and that means an anxious nation is obsessively refreshing FiveThirtyEight’s election forecast.

Nate Silver is, of course, the creator of that forecast, and the founder and editor-in-chief of FiveThirtyEight. His forecasting model successfully predicted the outcome in 49 of the 50 states in the 2008 US presidential election and all 50 states in 2012. And in 2016, Silver’s FiveThirtyEight gave Donald Trump a 29 percent chance of victory, and Silver was rare among analysts in emphasizing that meant Trump really could win.

So I asked Silver to join me on my podcast to talk about what’s changed since 2016, what’s new in his forecast this year, whether the polls can be trusted, how the electoral geography is reshaping campaign strategies, how Biden’s campaign strategy has worked, whether Trump is underperforming “the fundamentals,” and much more.

An edited transcript from our conversation follows. The full conversation can be heard on The Ezra Klein Show.

Subscribe to The Ezra Klein Show wherever you listen to podcasts, including Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, and Stitcher.

Ezra Klein

What went wrong in the polls in 2016?

Nate Silver

Well, there are degrees of wrong. Polls often miss an election by 2 or 3 or 4 points, which is what happened in 2016. Ahead of an election, people need to be prepared for the fact that having a 2- or 3- or 4-point lead — which is what Clinton had in the key states — is not going to hold up anywhere close to 100 percent of the time. You might win 70 percent the time, like in the FiveThirtyEight forecast.

That said, there are a couple of things that are identifiable. One is that a bulk of the undecided voters in three key states — Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania — went toward Trump. If those undecided voters had split 50-50, Clinton would have won nationally by 5 or 6 points.

The thing that I think you blame pollsters for is education weighting. If you just randomly call people in the phone book or use a list of registered voters, traditionally, you get older people more than younger people, women more than men, and white people more than people of color. So polls weight responses to account for those disparities.

But it’s also true that people who are college-educated are more likely to respond to polls. It used to be that there was no real split along educational lines in who voted for whom, but now — at least among white voters — there’s a big split between the college-educated Biden and Clinton voters and the non-college Trump voters. So if you oversampled college-educated white voters and undersampled non-college white voters, you’re gonna have a poll that leans toward Clinton too much.

Ezra Klein

Two questions on that, then. First, how does Biden’s lead compare to Clinton’s in 2016? And second, do you think pollsters have corrected the mistakes they made in 2016, such that their polls are likelier to be reliable this year?

Nate Silver

First, let me back up and say, Trump can still win. In 2016, our final forecast said Trump had a 29 percent chance, and that came through; right now we give him a 12 percent chance to win in November. That’s not trivial, but it is a different landscape.

One difference is that there are fewer undecided voters this year. In 2016, there were about 13 or 14 percent undecided plus third party; it’s around 6 percent this year. That’s a pretty big difference. So that first mechanism that I described that helped Trump is probably not going to be a factor. Trump could win every undecided voter in these polls and he would still narrowly lose the Electoral College.

Biden’s lead is also a little bit larger. After the [FBI Director James] Comey letter, Clinton’s lead went down to 3 or 4 points in national polls and 2 or 3 points in the average tipping point state. Biden is ahead by more like 5 points in the average tipping point state.

We can definitely find cases in the past where there was a 5-point polling error in key states — that’s why Trump can win. But a 2016 error would not be quite enough: If the polls missed by exactly the same margin, exactly the same states, then instead of losing those three key Rust Belt states by 1 point, Biden would win them by 1 or 2 points. He might also hold on in Arizona, where the polls were fine in 2016. So it would be a close call, but one that wound up electing Biden in the end, pending court disputes, etc.

Ezra Klein

The data analyst David Shor shared a chart showing that the 2018 polls were still underweighting Republican voters in some of those same Midwestern states they did in 2016. Even though they were trying to use education as a proxy and weighting it differently, it still didn’t fully measure what was getting missed in the Republican electorate.

Do you think that the way those states are being polled in 2020 is better?

Nate Silver

It’s possible that even within, say, the demographic group of non-college-educated people, Trump supporters just answer your polls less. That’s always a concern.

But there is a long history of the direction of polling error being unpredictable: If the polls miss in one direction — say, the Republican direction — in one year, then they’re equally likely the next year to miss again in the Republican direction or the Democratic direction.

That’s because polling is a dynamic science and pollsters don’t want to be wrong. They particularly don’t want to be wrong the same way twice in a row, so they will make all types of new adjustments. So polls can be wrong, but it’s hard to know in which direction they’d be wrong if they were wrong.

Ezra Klein

I think it is easy to imagine for people how the polls could be wrong in Donald Trump’s direction, because people lived through that and have a visceral feeling of it. But as you often point out, in 2012 the polls were a little bit wrong, but in Barack Obama’s direction. If the polls were wrong in Joe Biden’s direction, what do you think would be the likeliest reason why?

Nate Silver

So I think you have a story that would start with the fact that maybe pollsters were not prepared for this early voting surge. You have likely voters in polls. That’s based on some combination of their vote history and responses. Well, some of those people won’t vote. Their car won’t start on Election Day, or they will have a Covid outbreak in their area. However, if you’ve actually already voted, then you’re 100 percent likely to vote. So it may be that Democrats weren’t given enough extra credit for early voting.

It’s also worth thinking about incentives here. Imagine you’re a pollster and you have a choice between two turnout models. One is a newfangled turnout model that accounts for early voting. The other is a more traditional, conservative model.

One of them has Biden up 6 points in Wisconsin. And one has him up 10 points. There’s not much incentive to publish the 10-point lead. If Biden wins by 10 when you had him up by 6, people will say it was a pretty good poll nevertheless. But if Trump wins, you’re going to look that much worse. So I think there are a lot of incentives to be sure that you’re not missing the white working-class voters that may not apply to Hispanic voters in Arizona or to younger voters who have not been reliable voters in the past but are evidently turning out this year.

Ezra Klein

As we’re speaking, the FiveThirtyEight forecast has Biden at an 88 out of 100 shot of winning the election and has Trump at a 12 out of 100 shot. We’ve been talking about the probabilities on one side of that distribution, the one where Trump wins. What does the outcome look like on the other side? In the 12 percent of best-case scenario outcomes for Biden, what is he winning?

Nate Silver

A 5-point polling error in Biden’s favor means he wins by 13 or 14 points. That would be the largest margin of defeat for an incumbent since Hoover. It would exceed the margin that Jimmy Carter lost to Ronald Reagan in 1980. It would mean that Biden would win almost all of the states that are commonly considered competitive, including probably Texas, Ohio, Iowa, and Georgia.

Once you get beyond Texas, there aren’t many other close toss-up states. In a lot of our simulations, a good Biden night tends to peak at him winning Texas. Beyond that would take a really big polling miss.

Ezra Klein

I think one of the really interesting things you’ve done in the FiveThirtyEight model in 2020 is add an uncertainty index. What goes into that index, and what has it taught you so far?

Nate Silver

We analyzed lots of factors that historically are correlated with uncertainty and they point in opposite directions this year. On the one hand, the fact that you have few undecided voters and few third-party voters. The fact that you have stable polling and higher polarization — those all lead the model to be more certain about the outcome.

But there are other factors that point in the other direction. The two most important ones are the degree of economic uncertainty and the amount of news. This last one has become infamous. We use an index based on how many full-width New York Times headlines there are. The more of those you have, the more uncertain the news environment. When, for example, Donald Trump got Covid-19, that was a banner headline at the New York Times for three or four days. That is something that moved the polls. But for the most part, these monumental events have not moved the polls very much.

When the US first had our Covid crisis, initially, there was a little bit of a sympathy bounce for Trump that began to wear off. Then in June, when you had this second peak more in Southern states plus the George Floyd protests, that moves things a little bit. But you have these monumental historic events and you go from Trump minus 6 to Trump minus 9. That’s not nothing, but it means like 1.5 percent of Americans are changing their vote. So people seem pretty darn locked in about how they feel about Trump and about Joe Biden.

Ezra Klein

I wrote a whole book about polarization, and one of the big arguments I make is that as polarization goes up, American politics becomes more stable in terms of people’s preferences because the decisions are clearer for them. You all put that into the model.

But if you had told me a year ago what was going to happen over the next year — coronavirus, 200,000 Americans dead, the kind of economic volatility we’ve seen, George Floyd and the national protests — I would not have predicted that one year later his approval rating would be up by 1 point.

Are you surprised by the level of stability?

Nate Silver

I certainly think the hypothesis that polarization begets more stable public opinion is pretty sound. It has been tested in a pretty good way this year. Although one other prediction of polarized politics is that you get narrower outcomes. So you have more close elections.

I’m not sure that Trump was necessarily going to lose this election absent Covid. It’ll be a famous debate if he does lose. But if you look at what polls of Michigan, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania were saying in March or April, they were very close races — within a point or two. So things have shifted in ways that are meaningful, but only in relative terms.

One other funny thing about this election is that because of Trump’s Electoral College advantage, there is not much middle ground between a Biden landslide and an extremely competitive, down-to-the-wire photo finish.

If Trump beats his polls by 2 points, that’s a toss-up. If Biden beats his polls by 2 points, then it’s Obama 2008, which people consider a landslide. So the Electoral College edge makes a big difference and is why there’s been this very bifurcated, binary kind of world where we seem to oscillate between, “oh, my gosh, 2016 again” and “Trump is Herbert Hoover.”

The degree to which American political institutions lean Republican — and why that matters in 2020

Ezra Klein

There’s a finding by political scientist Alan Abramowitz that I think about a lot. He found that from 1972 to 1984, individual states would swing, on average, 7.7 points from one presidential election to the next. But since the 2000s, that change has been just 1.9 points. So there has been this really big drop in volatility.

It strikes me that there is a different incentive set for politicians who are at real risk of losing voters they had before as opposed to politicians who, basically no matter how they perform, are going to keep the voters they had before. I’m curious how you assess that.

Nate Silver

There are two big fundamental things that govern every aspect of American politics. Number one is the increasing degree of polarization. It’s probably the most robust trend of the past 30 years that shows up in all types of ways. Number two is the GOP advantage in political institutions, particularly the Senate, because of overrepresentation of rural areas.

We talked before about what a landslide it was when Obama won in 2008. He won by 7 points. The GOP has about a 6- to 7-point inherent advantage in the Senate, meaning that the median state is around 6 points more Republican in the country as a whole. So Democrats can win, but only if they win in a landslide.

That has a couple of implications. One is that you have public policy catered to an older, more rural, whiter electorate. The GOP does not take advantage of that by saying, we’re going to win every election for all of eternity — we can have a stable, majoritarian coalition. Instead, they say, we’re going to actually pass very aggressive policies that the median voter would not like. But we don’t need to win the median voter. That governs a whole lot of decisions that they make.

Ezra Klein

How does that change for Democrats if they add DC and Puerto Rico decides to become a state as well? How would that change the Senate map?

Nate Silver

That shifts it to around a +4 for Republicans. If Democrats were to add DC and Puerto Rico and divided California in thirds, where all those Californias were at least somewhat blue, then the Senate would be still a +2 lean Republican.

Ezra Klein

What does the Electoral College partisan lean look like to you? How big is the GOP advantage there? And how durable is that advantage, given what demographics look like going forward?

Nate Silver

It was about 3 points in 2016. Clinton lost Wisconsin by about a point when she won the popular vote by 2 points. It looks similar for Biden — around a 3-point gap.

I do think the Electoral College gap is more ephemeral. In 2008 and 2012, if you had had a photo finish election like you had in 2016, Obama would have won the Electoral College — he outperformed his national margins in the tipping point state. So it can flip back and forth pretty easily.

If Texas flipped, that would make a big difference. The one state that is underrated as a problem for Democrats, though, is Florida, which has a ton of electoral votes. Florida, if anything, has been one of Biden’s worst states this year relative to the fact that he’s ahead by 8 or 9 points nationally.

Ezra Klein

Do you have an estimate on how big the Republican lean is in the House?

Nate Silver

It’s a little hard to estimate in the House because the advantage is partly is tied into incumbency; once you gain the incumbency advantage like Democrats have now, that can be hard to overcome. But it’s probably around 3 or 4 points. It’s been a bit of a moving target because in 2010 you had a very Republican year, so you had a lot of gerrymandering that favored the GOP. There’s also a lot of clustering of Democrats in urban areas. And most urban areas are more Democratic than most rural areas are Republican. That creates an inequity that makes the median district more Republican-leaning.

With that said, you had a lot of suburban districts that have become what are sometimes now called “dummymanders.” If the suburbs of Houston or Dallas were 10 points in favor of the GOP in 2010 and things have shifted by 12 points, then all of a sudden now you have it perfectly inefficiently configured the other way where Democrats narrowly win all these districts in Texas or the suburbs of Atlanta or California or whatnot. So that advantages is less profound now.

One other inequity here is that when Republicans get the trifecta in a state, they will, generally speaking, gerrymander as much as they can get away with. Democrats will often appoint some type of nonpartisan commission so they fight things back to 50/50.

One other thing to keep in mind is because the GOP gerrymanders were so effective in 2010 in some states, it’s hard for Democrats to win back the state legislature in states like Wisconsin. Usually you wipe the slate relatively clean after 10 years, but in a state where you don’t have a lot of demographic change — where it favors a party that already had a gerrymandering edge — that can become a repeating error that persists for decades.

Why Biden won the Democratic primary — and why he’s winning now

Ezra Klein

If the presidency was decided by the popular vote in 2016, Donald Trump would have lost. In that world, I think there would have been a lot of frustration among Republicans that the Trumpist faction of the party had nominated a candidate who blew a winnable election. And, maybe, because of that, the Republican Party would have reformed itself.

The Democrats have the opposite version of this: They have to win by pretty big margins at the presidential level, the Senate level, and the House level. They’ve actually responded to that, and Joe Biden was their response in 2020. Joe Biden was not the favorite pick of most Democratic factions that I know of, but he was an answer to the question: Who would be acceptable to white working-class voters in Wisconsin and Pennsylvania — the kinds of voters Democrats feared they were losing?

The polls seem to be indicating that this has been strategically successful — that Biden is actually changing the coalition. Do you think Biden has actually changed the coalition? Or do you think this election would be the same under any Democrat?

Nate Silver

In the primary, you had a fairly explicit contrast between Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden. Bernie’s pitch explicitly was: We are going to win this with a high turnout of younger people and people of color. We’re the biggest coalition. So we’re going to win and we’re going to win the White House that way, too. Turnout, turnout, turnout.

Whereas Biden is about persuasion and the median voter. The median Democratic voter liked Medicare-for-all but liked the public option a little bit more and felt like it seemed a little safer electorally. For better or worse, Joe Biden’s pitch has come true: The reason he is way ahead in these polls is not because Democratic turnout is particularly high relative to GOP turnout — it’s because he’s winning independents by 15 points and moderates by 30 points. He’s winning back a fair number of Obama-Trump voters and keeping a fair number of Romney-Clinton voters. The story the polls are telling is that Biden is persuading the median voter not to back Donald Trump.

Biden is a throwback politician in so many ways. He’s also a throwback in the sense he’s very coalitional. He’s not a very ideological guy. He gets branded as a moderate, which I think also reflects the bias that if you’re an older white man you can have the same policy positions but will be branded as much less radical than a young Latina might. But still, he’s able to perfectly calibrate himself to what the median Democratic voter wants, and is good about listening to different coalitions within the party. That’s why he’s been successful over a long time. He’s very transactional and good at listening to different demands from different party constituencies.

Ezra Klein

After Democrats nominated John Kerry and lost to George W. Bush In 2004, there was this view that the Democrats have to win back the heartland. They started thinking about guys like Brian Schweitzer in Montana. And then what actually happens in 2008 is they run Barack Hussein Obama from Chicago, Illinois, and have this gigantic victory.

This is a way in which the immediate post-election punditry really fails. There is a desire to refight the last war. Democrats were responding to ’04, but ’08 was just a different election in a different context and something else ended up working.

I think that’s happened here, too. One of the dominant views after 2016 was Donald Trump gave people something to vote for. You may not like him, but at least he doesn’t think the system is okay. So there was a rise in politicians who responded to that. Populist politicians on the left like Bernie Sanders or, in a different way, Elizabeth Warren. Other kinds of figures on the left who try to match Donald Trump’s energy but really push hard on a diversifying America.

And here comes Joe Biden with what is almost a strategy of being inoffensive — he has popular policies, he says nice stuff. And what you see in these polls is 70-30 Trump voters say they’re voting for Trump, not against Biden. And roughly 70-30 Biden voters say they’re voting against Trump, not for Biden. And Biden is way ahead!

In a way, Donald Trump provides the enthusiasm and Joe Biden just keeps denying him something really significant to run against. Biden has this weird rope-a-dope of an election strategy that seems to be paying off.

Nate Silver

I think to say 2016 was about enthusiasm is a misdiagnosis. If you look at David Shor’s work, he’s tried to break this down. Probably 80 percent of the shift toward Trump was Obama to Trump voters, and because of persuasion, not turnout. One basic piece of math behind that is that if I persuade you, Ezra, to switch from Trump to Biden, that’s a net +2 for Biden. You were -1, now you’re a +1. If I turn someone new out for Biden, that’s only a +1. So persuasion matters more.

Ezra Klein

I want to go back to the Bernie theory because I think we weren’t 100 percent fair on it. The Sanders campaign had a real theory about low-attachment voters — people who don’t turn out. And the idea was that those people don’t turn out because they aren’t given a clear enough choice. But if you propose ambitious policies like Medicare-for-all and the Green New Deal and others — something the Bidens and Clintons of the world haven’t done — those folks will have a reason to vote.

That didn’t really pan out in the primary. A lot of those people didn’t come out to vote for Bernie Sanders. And that raises the question: Why don’t people vote? We often have turnout in the 50 to 60 percent range for presidential elections. What do we know about these marginal voters — people who may turn out but often do not?

Nate Silver

Generally, the idea that your views on 10 or 12 different issues are highly correlated makes sense for strong partisans, but that doesn’t make sense for a lot of voters. There was a great episode of The Daily where they randomly picked voters to talk about the Amy Coney Barrett [Supreme Court] nomination.

There was one woman said, “Well, I’m pro-life, but if I’m really pro-life, then is Donald Trump really the pro-life candidate in this election?” She’s thinking more broadly about what that means, so she probably feels very conflicted. She likes Donald Trump’s Supreme Court picks; she doesn’t like his treatment of women or how he acts on Twitter or that he doesn’t seem to want to have a health care policy in the country. So I think as things become more polarized, then the people who drop out tend to have more heterodox political views.

There are also people who feel like it’s going to be hard for them to vote or their vote doesn’t matter. Voter suppression has different effects based on different time spans. In the short run, if you try to suppress the vote and people find out about it, they might be more motivated to vote. In the long run, though, if I know that every time I have to vote, there’s a long line, that can have a cumulative effect.

Ezra Klein

One implication of the polarization conversation we were having earlier is that there is less of a penalty for nominating candidates who are more ideologically extreme. Even if you think Ted Cruz is really conservative or Donald Trump is kind of nuts, you just can’t stand Hillary Clinton, so you vote for Trump or Cruz anyway. Or, on the other side, even if you think Elizabeth Warren or Bernie Sanders are too liberal, you aren’t going to vote for Donald Trump, so you support a candidate more liberal than you are.

So do you think it actually would have made much of a difference if Sanders were the nominee? How differently from Biden do you think he would have performed?

Nate Silver

So we actually find that there still is a pretty big effect from where you line up on the issues. It’s a little bit hard to define liberal versus conservative, so we look at how often members of Congress vote with their party. Members who break with their party more often do quite a bit better, other things held equal. And that advantage has not diminished since 1990, which is when our data set starts off.

I think that Bernie would have given Trump a different vector to campaign on, where he could say, “the socialists are coming!” He’s trying to say Biden is a Trojan horse for AOC [Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez] and Bernie and Warren. Maybe that argument works for some voters, but you’re also conceding that Biden himself isn’t that bad, which is a weird strategy.

Look, Biden’s up by 8 or 9 points. I think the penalty for being more left is probably not enough to make Sanders an underdog — he’d be the favorite. But I do think when we kind of look at this stuff and measure ideology, it seems to have an effect.

Now, Bernie could have been effective for other reasons. One thing where I think Biden’s people have not done very well is signing up new people to vote. They also were not doing a lot of door-knocking operations until recently. So Bernie would have done certain things better. But I’m someone who still believes in the median voter theorem, I suppose.

Ezra Klein

Let me ask about the flip of this: Donald Trump. Trump has never won an election with more voters. He has never been above 50 percent in average approval ratings. Do you think another Republican candidate, a generic Republican, would likely be in a stronger position today than Trump?

Nate Silver

One big question that’s pertinent to how we think about this election is where do the fundamentals point in our specification? That’s a very nerdy way to put it. But we actually think that a generic Republican should be running neck and neck with a generic Democrat because the economic recovery was pretty robust in the third quarter and because you have an incumbent and incumbents usually get reelected more often than not.

If you look around the world, approval ratings for many leaders went up during the early stages of coronavirus. I think if Trump showed some basic empathy uncovered and just said the right things and didn’t get in the way of basic things that every country needs to do — and then we have this 30 percent GOP rebound in quarter three — I’m not sure that he’d be losing his campaign. At the very least it might be close enough where his 3-point Electoral College edge would come in handy for him. So he has not been a very effective politician from an electoral standpoint.

Why Silver thinks we shouldn’t be too worried about the possibility of an electoral crisis

Ezra Klein

When we talk about elections, I think people mentally index to the idea that there are two outcomes: win or lose. And in this election, it seems to me there are three: win, loss, and crisis.

When we talk about, say, the possibility of a 3- or 4-point polling error in Donald Trump’s direction, that would make the election very close in the key swing states. In the world where you have lots of mail-in voting because of Covid-19, a bunch of Republican attempts to prevent or discredit those votes, and a Supreme Court with Amy Coney Barrett possibly having the last word on election rulings, that’s a situation where we could face a real legitimacy crisis over who won. As crazy as Bush v. Gore was, I really worry that if you replay that now, it gets a lot crazier.

Your models explicitly do not try to measure the effect of electoral chicanery, but I’m curious how you think about that possibility.

Nate Silver

I always worry about these conversations because the chaos scenario is so bad that whether it’s 2 percent or 5 percent or 15 percent, you still have to be very worried about it. And it’s certainly somewhere in the low to mid-single digits, if not a quite bit higher — although not the modal outcome by any means.

But I think there are a couple of things to keep in mind. One, people forget just how close Florida was in 2000. It came down to something like 537 votes in a state with 10 million people. That’s not just within the recount margin — it’s exactly on the nose. And it’s still quite ambiguous who ultimately really won Florida, depending on dimpled chads and the butterfly ballot in Palm Beach County and everything else.

Two, the issue most likely to affect the debate is ballots that are returned after Election Day. Those actually aren’t that many ballots, and may not be as Democratic as people assume because Democrats are being more diligent about sending their ballots in early. If you look at mail ballots returned so far, Democrats have around a 30-point edge on partisan ID in terms of who has returned more ballots; if you look at the mail ballots that have not yet been returned but were requested, it’s only a 12-point edge for Democrats.

It’s possible that the attempts at voter suppression can backfire if they make the people you’re trying to suppress more alert. You can imagine Democrats being more diligent about getting their ballots in early, finding different ways to vote, following all the rules — in which case, these things might not help the GOP.

The last thing I think about a little bit is: Is it harder or easier to vote than it has been in the past? You’re always calibrating a model based on past history. There has always been voter suppression that disproportionately affects people of color and people who are more likely to be Democrats. That’s priced into the models.

However, it’s probably easier to vote now in most states than it ever has been. The Brennan Center does a write-up every year on the voting rights that passed in the past year. And for the past couple of years, you’ve actually had more pro-voting laws than voter suppression laws, which is different than the era from 2012 to 2016. So it’s probably easier to vote now than it has been in the past. And that could potentially help Democrats.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Ezra Klein

Read More