Junji Ito’s horror has been thoroughly memed — but his new anthology, Venus in the Blind Spot, is still terrifying.

One Good Thing is Vox’s recommendations feature. In each edition, find one more thing from the world of culture that we highly recommend.

If you’ve heard of horror manga creator Junji Ito, it’s probably through the internet fame of his most well-known short story, “The Enigma of Amigara Fault.” That story, about a Japanese town whose inhabitants become obsessed with fitting themselves inside terrifying mysterious human-sized shapes carved into a mountainside — “finding their hole” — has become a horror mainstay as well as a meme since its publication in 2003. It’s also an encapsulation of the convergence of Lovecraftian cosmic horror and mundane fear that typifies Ito’s work.

Now, a new anthology from Viz, Venus in the Blind Spot, collects many of Ito’s best-known short stories, including “Amigara Fault,” and offers a great introduction to Ito’s work. The 10 collected short comics — since this is manga, you read each panel from right to left on the page — showcase the pure scope of Ito’s imagination, as well as his ability to envision terrifying phenomena in the most unassuming places.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21824502/Screen_Shot_2020_08_28_at_9.10.11_AM.png) Viz

VizThroughout these stories, everyday life becomes a series of looming potential terrors. In fact, though almost no one could have seen it coming, Venus seems almost eerily timed for release during a pandemic. The first story, “Billions Alone,” feels like it was conceived with a vision of a world under quarantine. It wasn’t — the story was first published in 2002 and adapted from a popular Japanese urban legend. But even though I first read this story years ago, Ito’s vision registers as new, and even obscene, in its straightforward depiction of a society that seems committed to its own destruction.

“Billions Alone” plays out through the point of view of an agoraphobe who rarely ventures outside. But the character’s tenuous link to the world becomes even shakier when a strange phenomenon grips the nation and an unknown killer, or killers, begins to target mass group gatherings by sending eerie messages over the airwaves: “Let’s all hold hands … billions alone …”

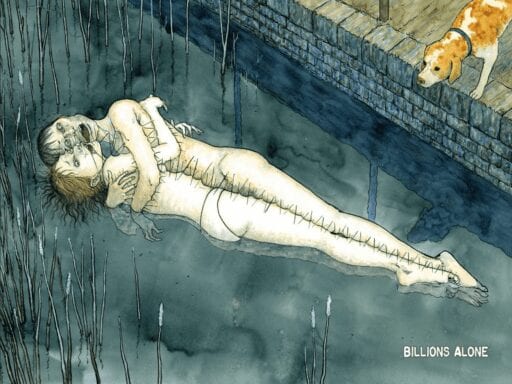

Through brainwashing and an inexplicable mysterious power, people gathered in groups around the city begin to vanish, only to reappear days later, sewn together in horrific, phantasmagorical shapes and assemblages. This story predates the infamous 2009 film The Human Centipede by seven years, but there’s really no comparison between that campy mess and Ito’s artistry, which renders his monstrosities as deftly sketched fever dreams:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21824412/Screen_Shot_2020_08_28_at_7.56.28_AM.png) Viz

VizFrom there, the allegorical similarities to the Covid-19 pandemic mount rapidly. Authorities seem helpless to act swiftly or know what to do in the face of the mysterious bringer of death. Many people stubbornly refuse to stop holding large social gatherings, despite the near certainty of attracting the mass-murdering phenomenon. Ito’s conclusion raises new questions more than it provides answers, but in true Lovecraftian fashion, the glimpse of an answer he provides is nightmare-inducing.

The rest of Venus in the Blind Spot doubles down on the eerie unfathomable logic of Ito’s nightmarish visions. Again and again, his characters fight mysterious compulsions to become one with some ghastly, unutterable phenomenon they can neither understand nor control. It’s the voices on the radio waves, urging you to hold hands and partake in some diabolical ritual; it’s the chair crying out for you to be “held,” the mountainside hole calling for you to find it and fit yourself inside. There’s a symbolic terror of connection that emerges throughout Ito’s work, but also a kind of deep primal need to become one with whatever one fears. Again and again, his characters fall prey to their own darkest imaginations; again and again, they ultimately embrace their own madness and the evil awaiting them with a kind of raw, mad joy.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21824493/Screen_Shot_2020_08_28_at_9.04.02_AM.png) Viz

VizIto didn’t begin drawing and writing until he was in his 20s, which perhaps explains why so much of his horror is concerned not with the stuff of childhood — few creepy dolls or terrifying ghosts appear in his work — but with the challenges of modernity and adult life: fear of social gatherings, fear of intimacy, fear of loss of reputation. Born in 1963, he had a relatively uneventful childhood (though he did live in a house that required walking down a harrowing underground tunnel to get to the bathroom, which definitely seems like the kind of childhood event that turns someone into a horror writer). Ito started experimenting with art and horror writing while working as a dental technician. He became a huge fan of “weird fiction” as well as the stories of mid-century mystery and horror writer Edogawa Ranpo. He even adapted some of Ranpo’s stories, including “The Human Chair” and “An Unearthly Love,” both of which appear in the Venus anthology.

Ito’s attempts at publishing were initially successful — his 1987 debut story, “Tomie,” about a girl who returns from the dead, is still one of his best-known. He gained greater fame with his most well-known longer story: the sprawling 1998 manga series Uzumaki, or Spirals. The series follows a contagion, of sorts, in which characters grow fatally obsessed with, and terrified of, spirals, which occur naturally in nature and so are everywhere. Many horror fans consider Spirals a modern masterpiece; however, a film adaptation released in 2000 was lackluster, because live-action cinema fails to capture the drama of Ito’s surreal visual style in giving life to his characters’ psychological obsessions.

That’s one reason Ito’s short stories are such digestible page turners — the power of his garish, monstrous artwork is as transfixing as the stories he’s telling. The stories themselves, in fact, are often secondary to the way they’re being told; Venus in the Blind Spot is perhaps a more adult version of the 1981 anthology Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark, whose fantastical original artwork by illustrator Stephen Gammell made the series a childhood staple and a source of primal terror for many ’80s and ’90s kids.

With Ito, however, you’re not getting the type of horror juvenilia that lends itself to campfire stories, but rather creeping, gnawing dread, the psychological horror that turns everyday doubt and fear into looming existential anxiety. I rarely have nightmares, but while reading this collection, I had one — the kind of impossible to explain but equally impossible to shake off dream that lingers for days, much like Ito’s storytelling.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21824473/Screen_Shot_2020_08_28_at_8.09.51_AM.png) Viz

VizPerhaps none of his short stories typifies Ito’s appeal as much as the title story of this collection, “Venus in the Blind Spot,” about a girl named Mariko who’s obsessed with spotting UFOs, and the men who love her. Whenever Mariko comes near the men, she vanishes from view; she’s only visible to them from far away.

Once again, Ito plays with a symbolic fear of intimacy and connection. But even more, he captures something about the ephemeral nature of horror itself: When we look at it directly, it slips from our view; it’s only at the edges of our vision or from a distance that we can see true terror most clearly. By the time we get near enough to see it up close, it’s too late to save ourselves; we’ve already become engulfed in the abyss.

Ito’s genius lies in his understanding that even though we should know better, humans will always succumb to the inexorable urge to draw closer anyway. And that’s the most terrifying thing of all.

Help keep Vox free for all

Millions turn to Vox each month to understand what’s happening in the news, from the coronavirus crisis to a racial reckoning to what is, quite possibly, the most consequential presidential election of our lifetimes. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work, and helping everyone make sense of an increasingly chaotic world. Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Aja Romano

Read More