Friday is the first day of jury selection in the trial against former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger.

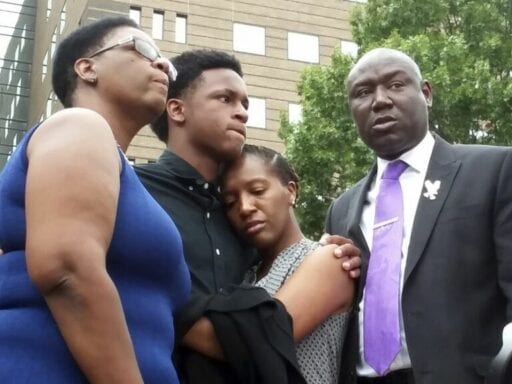

Friday marks the first anniversary of the death of Botham Shem Jean, a 26-year-old accountant and native of St. Lucia who was fatally shot in his home by Amber Guyger, who was then an off-duty Dallas police officer. It is also the first day of jury selection in a murder trial that is sure to involve controversy and heated discussion.

Jean’s death immediately drew national attention, raising questions about what led to the unarmed black man being shot inside his own apartment. These are the known facts: Guyger, a four-year veteran of the Dallas Police Department, and Jean’s downstairs neighbor, had gotten off of a work shift on September 6 when she returned to her Dallas apartment building. When she arrived, Guyger got out of her car, then entered Jean’s apartment, firing at the man soon after and hitting him in the chest. Guyger then called 911, but Jean died of his injuries at a nearby hospital.

Beyond these details, though, the explanation for what happened that September night differs depending on whose perspective is centered. Guyger says that she didn’t realize that she was on the wrong floor of her building and that the apartment she was in was not, in fact, hers. Seeing a “large silhouette” in the dark apartment, she said she thought she was being burglarized, and fired her weapon after giving “verbal commands.” She then turned on the lights in the apartment, and called 911.

In an interview with the Texas Rangers shortly after the shooting, Guyger said that she did not realize her mistake until she looked at the apartment number outside the door. Her lawyers are expected to argue that the shooting was a tragic mistake, but that Guyger was allowed to defend herself if she thought an intruder was in her home, even if she was not actually in her apartment.

Jean’s family and Dallas prosecutors view things differently. They argue that Guyger’s account doesn’t add up, with the family noting last year that she should have noticed details alerting her to being in the wrong apartment, like a red doormat outside Jean’s door. Official documents in the case have also sparked confusion: A September 7 search warrant from the Dallas Police Department describes a very different account of the shooting than what was included in a September 9 arrest affidavit compiled by the Texas Rangers, the law enforcement agency tasked with the initial investigation of the shooting.

Guyger was initially charged with manslaughter and was not taken into police custody until three days after the shooting, fueling accusations that she was being shielded by the police department. She was fired in late September, after the department argued for weeks that she could not be immediately terminated. In November, she was indicted on murder charges by a grand jury.

This month’s jury selection follows delays in the trial date, now set for September 23, and an ongoing fight between the prosecution and Guyger’s attorneys over if the case should be tried in Dallas. As the defense argues that their client made a mistake and the prosecution charges that Guyger fired at Jean with the intent to kill, the former officer’s fate will ultimately be left to the jury.

Yet the shooting has raised bigger questions. It adds to an ongoing national conversation about police use of force and has prompted a discussion of how Dallas police treat residents of color — meaning that the outcome of the trial will likely draw as much attention as the shooting that facilitated it.

Botham Jean’s death sparked a conversation about race and policing in Dallas

The Jean case isn’t what comes to mind when we think of police shootings. But the ways that black people have historically been affected by police violence have influenced how this case has been discussed from the beginning.

That’s partly because the Jean shooting was initially handled like an officer-involved shooting, and Guyger only began to be treated like a civilian after it was clear that she shot Jean while off-duty. But the fact that she wasn’t immediately taken into police custody, and that she was allowed to remain free on bond, led Jean’s family to argue that she was being given preferential treatment.

Jean’s family also voiced concerns about what the police did and did not share in the early days after the shooting, particularly following reports highlighting that a small amount of marijuana was found in Jean’s apartment.

Lee Merritt, an attorney representing Jean’s family, called the warrant’s contents evidence of a “smear campaign” against Jean. In an interview with the Washington Post last year, he said that the warrant fit into “a familiar pattern” seen in police shootings involving black victims.

“It’s a systemic issue,” Merritt said. “We’ve been conditioned to associate black people with crime.”

As the investigation into the case continued, politicians like Beto O’Rourke, at the time a candidate for the US Senate, said that the shooting was yet another example of how “young black men continue to be killed in this country without accountability, without justice.”

The Jean shooting differs significantly from on-duty police shootings, but it is also true that concerns over the case were amplified by how these other shootings have been handled. Generally, if police officers are charged in on-duty shootings, they’re very rarely convicted. The National Police Misconduct Reporting Project analyzed 3,238 criminal cases against police officers from April 2009 through December 2010. They found that only 33 percent were convicted, and only 36 percent of officers who were convicted ended up serving prison sentences. Both of those are about half the rate at which members of the public are convicted or incarcerated.

“Everything she did was [as] a police officer,” Allison Jean, Botham’s mother, said in a September 5 interview with the Dallas Morning News. “And if she was just a common citizen, we wouldn’t even be talking today because that person would be in jail by now.”

This was part of why activists and Jean’s family argued that his death was inseparable from other acts of police violence, setting off a series of protests last September. In October, Jean’s family filed a lawsuit against the city of Dallas, arguing that city officials and leadership of the Dallas Police Department “failed to implement and enforce such policies, practices and procedures for the DPD that respected Jean’s constitutional rights.”

“Officer Guyger was ill-trained, and as a result, defaulted to the defective DPD policy: to use deadly force even when there exists no immediate threat of harm to themselves or others,” the lawsuit says. The suit suggests, more broadly, that the department has a “pattern, practice, history and custom of using excessive force against minorities, including approaching them with guns drawn.” The civil lawsuit has been paused until Guyger’s trial concludes.

As Guyger’s trial prepares to get underway, some legal issues need to be resolved

Lawyers on both sides of the case are under a gag order, meaning that they have been barred from discussing the trial in the media for the past several months. But that doesn’t mean that things have been quiet: In April, for example, audio of the 911 call Guyger made the night of Jean’s shooting was leaked to Texas news outlet WFAA. In the call, Guyger can be heard saying, “I’m going to lose my job. I thought it was my apartment,” as she speaks with a dispatcher. The leak of the call prompted the Dallas Police Department to launch an internal investigation earlier this year.

Over the summer, Guyger’s lawyers argued that the case needed to be moved out of Dallas entirely, saying that public officials and “media hysteria” had biased the local community against Guyger, limiting her chances for a fair trial. Her attorneys have also argued it is improper to compare the Jean shooting to other incidents involving police, saying that media outlets had spread “the false narrative that merely because [Guyger] is white and Mr. Jean was black, the incident must have been racial in nature.”

Rather than holding the trial in Dallas, the lawyers want it to be moved to one of six other counties in North Texas. Local reporting has shown that any such move is likely to produce a jury that is whiter and more conservative than a jury in Dallas would be.

More than 4,000 people have been summoned to participate in jury selection in the coming week. District Judge Tammy Kemp says she will determine if the trial will be moved after the jury selection process begins.

Dallas police officers are reportedly preparing for the outcome of the trial as well, recently announcing that no more officers would be allowed to take time off during the trial.

As the trial moves toward its opening day, there are still many unknown variables. But one thing is clear: The questions, frustrations, and tensions that Jean’s death stirred last year are far from settled.

Author: P.R. Lockhart

Read More