How Oregon adopted a vote-by-mail system.

Steve Druckenmiller loved voting, and he loved elections, but he really thought voting by mail was a crazy idea. So when the subject came up during his interview for the job of elections supervisor in Linn County, Oregon, in 1984, he thought, Oh crap.

“Sir, I think it stinks,” Druckenmiller recalls telling Del Riley, then the Linn County Clerk, who interviewed him for the position. Mr. Riley looked at him, big eyes behind big glasses, and thanked Druckenmiller for coming in. Druckenmiller figured, Well, I almost had it.

But a few days later, Riley offered Druckenmiller the job of supervising elections in Linn, a square in western Oregon, south of Portland. Whether Druckenmiller liked voting by mail or not, he was about to learn from the master.

In Oregonian politics, Riley is sometimes known as the “father” of vote by mail. Riley started asking why not let constituents send in their ballots. He became an advocate for the system after pioneering, along with neighboring Benton County, the state’s first vote by mail for local elections in 1981. Oregon’s vote-by-mail system has changed and expanded since, but that democratic experiment was a forerunner to how Oregon does elections now.

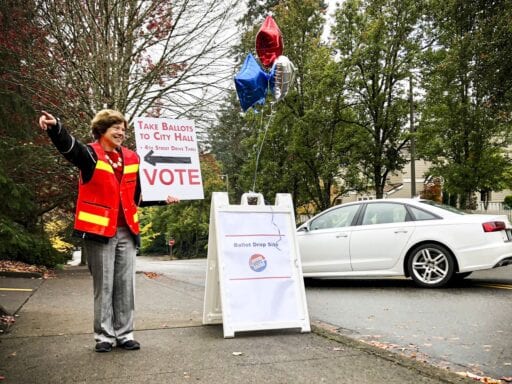

Today, Oregon votes only by mail. It has done so for nearly two decades, after voters approved a ballot measure in 1998. Across Oregon, registered voters are sent a ballot, and they can either mail it back or drop it off.

That has made Oregon’s system a vote-by-mail model for the country. Other western states, including Colorado, Washington, and Utah, have since adopted similar systems in the years since. Advocates say it’s as safe as in-person voting, cost-effective, and boosts turnout. They argue it could — or should — be the future of how America votes.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912668/GettyImages_620630428.jpg) AFP via Getty Images

AFP via Getty ImagesDruckenmiller, after working for Riley for a bit, asked his boss why he’d hired a vote-by-mail skeptic like him to run elections. “I thought after you did some vote-by-mails, you’d see it,” Riley told him. “Besides, you know what? You’re the only one who applied for the job.”

Riley was right. Druckenmiller did see it. When Riley retired, Druckenmiller was elected in 1986 to take his place as Linn County Clerk. He’s been running elections there ever since. By his count, he has probably run more vote-by-mail elections than anyone, anywhere — and he’ll be doing so again in 2020.

The rest of America is suddenly more aware than ever of how it votes this year. Covid-19 took hold in the United States during the primaries, forcing states to postpone elections and rethink their electoral systems. States and many constituents saw voting by mail or absentee ballot — safe at home, away from crowds — as the best way to protect people and guarantee access to the polls in the middle of a pandemic.

The number of Americans voting by mail has steadily increased in the past decade. In 2018, about 25 percent of all voters cast their ballots by mail. That number could about double in 2020. Beyond the states that already do it, this year, states like California, where counties already had many voters casting ballots by mail, are now also sending ballots to registered voters. Others, like Vermont and New Jersey, are mailing out ballots for the first time.

This rapid expansion of voting by mail is happening amid one of the most consequential and fraught elections in recent memory. How the election unfolds may determine whether counties and states begin to more readily embrace all-mail elections in the future, or whether the politics surrounding it becomes even more polarizing.

Oregon’s path to vote-by-mail offers some lessons for the rest of the country. Druckenmiller was a convert three decades ago. He believes you’ll be one, too. Just maybe not in 2020.

Vote by mail started in local Oregon elections

A delegation traveled to San Diego, California, in the spring of 1981. Riley, of Linn County, and others, including then-Republican Oregon Secretary of State Norma Paulus and some of her deputies, went to observe an all-mail election scheduled to take place there.

Paulus and Riley liked what they saw.

Riley, who passed away in 2018, and Paulus, who died in 2019, both saw voting by mail as a way to strengthen the democratic process. “The fundamental thing about Norma is she wanted to get everybody involved,” Pat McCord Amacher, a freelance writer who cowrote Paulus’s autobiography, told me. “And the thought that someone was not using the right to vote would have just been just unconscionable to her.”

First, though, they had to see if it would work in Oregon. In November 1981, Riley conducted the state’s first all-mail election, in Linn County; on the ballot were two school district levies and one city charter amendment. (Neighboring Benton County also got in on some of the action, as one of the school districts overlapped.) According to a 2018 op-ed in the Oregonian by Phil Keisling, Oregon’s Democratic secretary of state from 1991 to 1999, 25,000 registered voters received ballots, and turnout was as high as 75 percent for this little dinky election.

From there, a few additional counties in Oregon tested out vote by mail in local elections in the early 1980s, mostly for measures like school and library budgets, and later for local candidates as well.

Al Davidson, who was served as the county clerk for 20 years in Marion County, Oregon, which includes the state capital of Salem, said some resistance to vote by mail was driven by the fear that district and school measures would get defeated at higher rates, since people who wouldn’t normally be motivated or pay attention would now just vote everything down.

But it didn’t turn out that way.

Opposition to the idea “kind of died out,” he said. “It didn’t take very long before most Oregon governmental units realized vote by mail was the wave of the future, and rather than try to fight it, they needed to embrace it.”

Davidson admitted he wasn’t a big fan of vote by mail at first, and after he was elected in 1984, he told his staff that Marion County wouldn’t do it. But his staff convinced him, and after they conducted a few vote-by-mail elections and worked closely with other county clerks, Davidson decided he liked the results and changed his mind. “When I did, I was super champion of it,” he said. He became an advocate for expanding vote by mail across the state.

Davidson flipped in the same way Druckenmiller did. Druckenmiller said as an election administrator, it was hard not to be persuaded, once you compared polling place elections to vote by mail. Vote by mail was orderly, Druckenmiller said. It was accurate — you minimized the chances of error. You saw better turnout for special and local elections, and it cost less. You could better help voters, avoiding the crazy mess of Election Day and all the mistakes that happen at polling places.

“If you’re kind of a control freak, and you want something to be 100 percent, you would latch on to vote by mail,” Druckenmiller told me.

In 1987, the Oregon state legislature did latch on, and made vote by mail permanent for local elections, though not for primary and general elections. County clerks in the state kept pushing to make it permanent for all elections.

But that push turned a nonpartisan fight into something more political.

The political parties couldn’t agree on vote by mail. So Oregonians eventually decided for themselves.

Oregon experimented with vote by mail in a couple of statewide special elections in the 1990s, but the legislature largely frustrated any attempts to make it more permanent. In 1995, a bipartisan group in the Republican-led legislature passed a bill that would expand vote by mail for primary and general elections. The Democratic governor at the time, John Kitzhaber, vetoed it.

That’s partly because Republicans, not Democrats, were the early champions of vote by mail in Oregon.

“What that fear, or dislike, was coming from was the experience with absentee ballots,” Bill Bradbury, who served as Oregon’s Democratic secretary of state from 1999 to 2009, said of vote by mail during that time. Fresh in Democrats’ memories were recent elections in which absentee ballots had broken toward Republicans; Democrats reflexively thought that vote by mail would favor their opponents.

But as Keisling, the state’s former secretary of state, wrote in Washington Monthly in 2016, those particular complaints were more often made in private; publicly, Democrats instead “fretted about potential voter fraud and coercion. (Sound familiar?)”

Keisling, a Democrat, was secretary of state when the Democratic governor vetoed the bill in 1995. As a legislator, Keisling had voted against an expansion of vote by mail to party primaries in 1989. But as secretary of state — in charge of overseeing all elections in Oregon — he, too, experienced a conversion. The cost savings and the increase in turnout for local and special elections were too hard to resist.

“I finally had an epiphany,” Keisling told Oregon Public Broadcasting in June 2020, “and realized we were confusing a particular ritual of democracy with what its essence was, which was participation.” Vote by mail, he said, “clearly increased participation.”

In 1995, Keisling’s effort to expand vote by mail got an unexpected boost after a powerful senator from Oregon was forced to resign in 1995 following a sexual harassment scandal. That vacated a Senate seat, which needed to be filled through a special election. Keisling decided to conduct the primary and Senate election by mail.

That election, held in January 1996, featured then-Democratic House member Ron Wyden and then-Republican state Sen. Gordon Smith both vying for the open Senate seat. So much attention was on the race, Wyden recalled, that every time he walked outside about 40 boom mics, along with reporters, were eager to document the election.

Wyden won, edging out Smith to become the first senator elected in an all-mail election.

Turnout in that January election was about 66 percent, which broke previous special election turnout records, according to Keisling. Wyden’s victory also completely flipped the partisan divide on vote by mail. “Then Democrats say they love vote by mail. Republicans say, Oh bad, bad, bad. And Oregonians listened to all this and said, This is ridiculous. We like this, it makes sense,” Wyden told me.

When the Oregon legislature made another attempt to expand and make permanent vote by mail in 1997, it was the Republicans who killed it. “It was simply one of those cases of whose ox was getting gored,” as Druckenmiller put it.

But as Wyden noted, Oregon voters had by now gotten hooked on vote by mail. Local elections were being done this way. Oregon had also by this point embraced no-fault absentee voting for most other elections — meaning voters didn’t need an excuse to get an absentee ballot sent to them — and people took advantage of it. Election administrators were running in-person elections for a dwindling number of voters.

Over the years, vote by mail had become part of the democratic process. But politics still prevented vote by mail from being official. “That’s why we had to take it into our hands, because the legislature obviously wasn’t going to get there,” Davidson, still the Marion County Clerk at that time, told me.

Davidson and other county clerks and advocacy groups did take matters into their own hands: gathering signatures to get a vote-by-mail initiative on the ballot, so voters could vote on how they wanted to vote.

In 1998, Oregonians backed Ballot Measure 60 by 757,204 to 334,021 — nearly 70 percent — to allow vote by mail in all elections. “We knew once we got it on the ballot, the people would override the legislature,” Davidson said. “And that’s exactly what happened.”

How Oregon’s vote-by-mail system works

Bill Bradbury became Oregon’s secretary of state just before the first entirely vote-by-mail election in 2000. It went off without a hitch, which he credits to the 20 years of off-and-on experience with vote by mail Oregon already had.

Turnout in that general 2000 election was nearly 80 percent.

But even though the vote-by-mail ballot measure had passed overwhelmingly in 1998, the naysayers never shut up completely. “Every time you talk about changing voting systems, and every time you talk about voting by mail, immediately, people go to FRAUUUDDDD,” Bradbury told me, doing his best impersonation of the critics.

Yet Bradbury said he remembers no more than three prosecuted fraud cases in the primary and the general, which he said compared favorably to in-person elections. “I can say definitely there is not — N-O-T, not — an increase in fraud with vote by mail,” Bradbury said.

Oregon’s vote-by-mail system has safeguards in place. Registered voters have their signatures on file — either by mailing a voter registration card to election officials, or by opting-in to registration directly when they get or renew a license. When it comes time to vote, election officials mail ballots to registered voters, which they typically receive about two to three weeks before an election.

The ballot contains a few things: the ballot itself; a “secrecy envelope” that the ballot goes inside once it’s marked; and a return envelope, which now even has the postage prepaid so voters don’t have to cover the cost of return postage.

Once you make your choices on your ballot, you slip it into the secrecy envelope, seal it up, slip that into the return envelope and seal it. Then you read and sign the statement printed on the back of the envelope, which basically says that you verify that you are you. Once that’s done, you either send it back by mail or put it into a secure drop box — either method requires that election officials receive the ballot before 8 pm on Election Day. Oregonians can also track their ballot to make sure it’s been received and counted.

Only about one-third of Oregonians actually send their ballots back through the postal service, instead placing them in secure drop boxes at places like libraries or movie theaters or even McDonald’s.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912725/AP_00110702455.jpg) Jack Smith/AP

Jack Smith/AP/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912726/AP_041029010067.jpg) Rick Bowmer/AP

Rick Bowmer/APAccording to the Oregon Secretary of State’s office, from 2012 to 2018, slightly more than 36 percent of ballots were returned by mail; 63 percent of voters put their ballots in drop boxes or returned them directly to county officials. In the May 2020 primary, about half of voters sent in their ballots by mail, with both the Covid-19 pandemic and Oregon’s decision to start paying the cost of postage likely accounting for that uptick.

Each ballot has a unique bar code specific to each voter, so once the ballot is received, election officials can verify the signature on that ballot envelope to make sure it matches the one on that voter’s registration. There are often multiple reviews to guarantee it’s a match — Druckenmiller said if someone questions the signature, two other people will review it; if they’re not sure, he makes the final call. If the signature doesn’t match, voters are notified and given the opportunity to remedy that, in what’s known as a “cure” process.

But once a signature is verified, the ballot is separated from the return envelope so the ballot can be tabulated. Along the way, there are layers of auditing to make sure the number of ballots received matches the tabulated numbers for the vote count. Many see mail-in ballots as more secure because there’s a paper trail, and so cant be hacked.

Oregon election officials get updates from public records, like change-of-address notifications and death records, to check against the voter registration databases. “We use the Postal Service. When most of us move, we change our address, right?” Paul Gronke, a professor of political science and director of the Early Voting Information Center at Reed College in Portland, told me. “And so actually, vote by mail works really well and has very little deadwood. The rolls are very clean.”

John Lindback, the elections division director from 2001 to 2009 at the Oregon Secretary of State’s office, told me clerks even used to check divorce records to see if any spouse had ever tried to force an ex-partner to vote against their will. They never found anything.

According to the Oregon secretary of state’s office, in 2016, officials referred 54 cases of possible voter fraud to law enforcement. Of those, 22 people — representing just 0.0001 percent of all ballots cast that year — were found guilty of having voted in two states.

Election officials in Oregon I spoke to told me that vote by mail is also much more efficient to oversee than polling-place elections, where sites are spread out across the county.

“Clerks by nature are control freaks,” Lindback told me. With vote by mail, instead of having to staff dozens and dozens of election sites, people are staffed in the county elections offices instead. “They’re verifying signatures and processing ballots, and you have big tables of teams working on that,” Lindback said. “And you can look out there and go, Okay, everything looks like it’s going well. And you have way more confidence that everybody’s doing what they’re supposed to be doing.”

And if Oregonians are still skeptical, they can see for themselves. People are free to observe and monitor the process. That’s lately been more of a challenge because of coronavirus health restrictions — election officials already need more space to accommodate workers, and have to be cautious about protecting the people actually counting the votes — but Druckenmiller says over the years he’s had plenty of people come to observe and never had anyone leave with a complaint.

“When we were first implementing vote by mail, there was a higher level of concern about fraud,” Bradbury said. “And I can remember really going through that with people and trying to bring comfort to people. And I think people now are completely comfortable with the system in this state. We don’t hear boops about people complaining about fraud.”

Why the system has stuck

An April 2020 YouGov poll found that 77 percent of adults in Oregon backed vote by mail, compared to 11 percent who opposed it. Indeed, voters in states that have vote by mail — whether in bluer states like Washington or redder states like Utah — all tend to overwhelmingly like it.

It’s convenient. Voters don’t have to take off from work, or spend time waiting in line at a polling place. Sen. Jeff Merkley (D-OR), who was elected by mail and who’s backed legislation to expand vote by mail nationally, pointed out that it eliminates voter intimidation or suppression at the polls. Others noted how mail-in voting can adapt to crises, like the recent wildfires on the West Coast or unrest in cities including Portland, which could be a challenge if election officials had to set up polling stations.

Instead, voters get their ballots delivered right to them, and they can sit at their desks or their kitchen tables to fill them out. “It becomes sort of your civic evening,” Bradbury said. Some say it makes them more informed voters, because they have the time and opportunity to research candidates and ballot measures — which Oregon has its fair share of each year.

Lindback heard a lot from parents who said they liked vote by mail because it gave them a chance to show their kids what voting was all about. “It provides an opportunity, as you’re marking your ballot to have your kids there,” he said. “And you can talk about it, talk about the candidates.”

Advocates of vote by mail say it increases turnout, though some experts I spoke to said the gains are modest in high-profile national elections. Oregon did see an uptick in the 1990s and 2000s, but experts I spoke to attribute some of that to the novelty of it all, and the media coverage of the vote-by-mail elections.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912728/AP_20088488627495.jpg) Don Ryan/AP

Don Ryan/AP/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912731/AP_060527062.jpg) Don Ryan/AP

Don Ryan/APGronke, who’s studied Oregon’s system, said the benefits are much more obvious in state and local elections, which tend to be lower turnout and don’t attract as much attention. “The vote-by-mail system certainly encourages people to participate regularly,” he said. “There’s no doubt about that, because you get all that information.”

There’s also no evidence that vote by mail advantages one party over the other. Michael Traugott, a political scientist at the University of Michigan who’s studied this question, said that’s because America really has a two-tier electoral process: first, you register. Then, you vote. “Voting by mail didn’t produce extra registrations,” he said. “It gave people who were already registered a chance to vote.” Vote by mail can catch people who might have otherwise not made it to the polls, but it doesn’t transform the voter makeup of a county or state.

And then there’s why election officials love it. For one, it’s cheaper. Keisling wrote in 2016 that since 2000, exclusively voting by mail has saved Oregonians $3 million each election cycle. It costs money to set up dozens of polling stations in a county, staff them, and manage the equipment. Most states have some version of absentee or mail-in voting, and the more people that take advantage of that (as is expected to happen in 2020), election officials have to basically run two parallel elections. And again, for those control-freak county clerks, it’s much easier to administer.

Of course, no voting system is perfect, even if Oregonians will try to convince you otherwise.

Charlotte Hill, a policy researcher in elections and voting at the University of California Berkeley, told me that the social nature of voting does matter in elections; there’s a reason why it feels so hard to part with polling places. That could, in the longer term, diminish enthusiasm. “If we don’t give people an opportunity to, to feel like they’re part of that broader social unit when voting, I think there’s a chance that some people aren’t going to be as interested in participating,” she said.

Mail-in ballots also get rejected at higher rates than in-person ballots do. Oregon has tried to remedy that over time by improving ballot design, and implementing those robust “cure” processes so voters can correct mistakes. Still, 0.86 percent of Oregon’s ballots got rejected in 2016, though that was slightly below the national average.

Charles Stewart III, an elections expert at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, told me he has “not drunk the Oregon Kool Aid” on mail-in voting, but does think the state offers a case study for where and when vote by mail can work. It has tended to catch on in western states, where some people live great distances from county or city centers, so vote by mail makes even more sense. Oregon, he noted, has a strong tradition of political participation. The state also had decades of practice, even before the 1998 ballot measure, where Oregonians decided they liked mail elections and chose it for themselves.

Due to the pandemic, though, states and counties don’t have 20 years to ease into vote by mail. They’ve had just a few months.

The mail-in voting test for 2020

The outbreak of a pandemic in the middle of a presidential election year left states scrambling to figure out how to conduct voting safely and accessibly. Mail-in voting looked like the answer. But this rapid readjustment in how America planned to vote is creating even more uncertainty in an already tense election year.

Vote by mail is business as usual in places like Oregon and Colorado. States like California, which had already been moving toward mail elections, also had an advantage. But most other states had to figure out how to accommodate a greater share of the electorate staying home on a very short timeline.

In total, nine states (plus Washington, DC) are mailing ballots to all registered voters, including some like New Jersey that are trying this out for the very first time, along with overseeing polling place elections. Other states fall somewhere in between: Some are sending ballot applications, but not ballots themselves, to all registered voters. Others still require voters to request ballots, but have waived the requirement of providing a legitimate reason for voting absentee, or have allowed the pandemic to count as an accepted reason.

The result is likely an unprecedented number of Americans voting by mail.

But this great American vote-by-mail experiment in a contested presidential election has some of Oregon’s biggest advocates a little conflicted. On the one hand, they want everyone to join the vote-by-mail revolution. On the other hand, a revolution in an unpredictable presidential election year with tremendous implications for the future of American democracy is not exactly what they had in mind.

“We took 20 years to get it right,” Davidson, the retired clerk in Marion County, told me. “And people who have never done it, election administrators who have never done anything other than polling-place elections, it just scares me to death.”

Davidson said there are just too many variables, specifically in states that are now sending out ballots. There’s the equipment to process the ballots, and the training and administrative procedures, like cure processes to remedy discrepancies. Lots of places have rapidly changed their rules, and some states are still facing lawsuits, meaning procedures are changing weeks before the election.

Vote-by-mail states are much more used to communicating with voters by mail, and so, as experts have pointed out, tend to have cleaner voter rolls. But states adjusting rapidly may struggle, and some experts said they are looking to see if that means ballots go out to people who have died or moved — and, well, cue the voter fraud chorus.

“It’s best if you sneak up on this slowly,” Stewart, of MIT, said. “That’s one of the things I would have hoped that many of the states would have learned is that it does take a lot of work to make an effective transition to vote by mail.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912739/AP_506583979759.jpg) Don Ryan/AP

Don Ryan/AP/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912735/AP_100126126604.jpg) Don Ryan/AP

Don Ryan/APVoting-rights advocates are also nervous that the rapid shift to — or at least the increased emphasis on — vote by mail may confuse voters and deter them from voting. Hill, of UC Berkeley, said that when voting laws change, “People who turn out at lower rates or who might be more skeptical of changes in voting laws — people who have been more subject to voter suppression in the past — they are not usually the first adopters of the new voting system.”

States that are expanding their mail-in-voting options will also have in-person drop offs or polling places. This presents an additional challenge, with election administrators potentially having to run a mail voting process while still managing in-person polls, which requires even more resources and oversight to run because of sanitation and social distancing concerns.

Lindback, Oregon’s former elections director, told me that when he used to talk about Oregon’s system he’d tell officials, don’t do wholesale change, start gradually, let voters get used to it, and build from there. But the pandemic didn’t leave many good options.

And experts pointed out that because some states like Oregon do have well-established vote by mail, states have expertise to call on and techniques they can borrow. Laura Fosmire, a communications specialist with the Oregon Secretary of State’s Office, said in an email that the state’s director of elections has spoken with 30 other states since March about vote by mail.

Additional resources might have also helped smooth the transition, as states are already cash-strapped because of the economic crisis, and the election price tag is going up because of new procedures — whether preparations for mail-in voting or maintaining polling places during the pandemic. Democrats included $3.6 billion in funding for states to administer elections in their $3 trillion stimulus package, but that bill is indefinitely stalled in the Republican-led Senate.

In March, Sen. Wyden, who’s been introducing legislation since 2002 to expand vote by mail nationwide, and fellow Oregonian Sen. Merkley introduced legislation to try to help states expand vote by mail and no-excuse absentee voting, but it went nowhere. “Our good faith is to make vote by mail work,” Wyden told me. “The evidence has been overwhelming that it has been constructive.”

But a lot of that good faith has been eroded by partisanship, which has pitted Democrats and Republicans on opposite sides of the vote-by-mail issue. That partisan fight may end up being the biggest threat of all to the process, and to American democracy itself.

The biggest threat to mail-in voting is still misinformation

The ultimate test for mail-in voting this election won’t be the ballots, or the procedures, or the rejection rates. It will be the rhetoric, and the misinformation, around it.

A lot of this is coming from the president and members of his administration who’ve insisted that the rapid shift to mail-in voting is a recipe for fraud. Trump’s Twitter feed is a morass of conspiracies about missing ballots and Democrats stealing the election.

Vote-by-mail advocates worry this could have a disastrous effect on the popularity and wider adoption of mail-in voting. None expressed fears that 2020 would suddenly be fraught with fraud. Instead, they are concerned that if there are administrative problems or hiccups that come from this shift to vote by mail, the current climate will make the process seem sinister when it’s not.

If election administrators make mistakes, Druckenmiller told me, “it is going to seriously not only damage the presidential election, but is going to seriously damage vote by mail, which is a wonderful revolution in helping people vote.”

But Druckenmiller said neither side is really right in this situation — both parties are, again, mostly worried about whose ox is being gored. Democrats, he said, are acting like voting by mail is a simple way of doing elections, when it’s not. Trump and the Republicans are also wrong when they say it’s a tool of fraud, because it’s not.

“I’m shattered by some of this stuff, I really am,” he said. “They’re setting up elections officials for failure. We’re going to be called dishonest. I don’t know exactly what to do with it, except you try to stand in the middle and point out that both sides are completely missing the marker.”

A record number of people are expected to vote by mail, no matter what. The Republican-led attacks against it are already creating the conditions for voters to distrust the election results, no matter what they are. “This is a huge challenge of our time,” Hill said. “What do we do when one of the two major political parties is intentionally trying to reduce confidence in a widespread voting method? And I don’t think there’s an easy answer to that.”

Oregon election officials past and present told me they’re used to hearing concerns about fraud and other problems with voting by mail. Heck, some of them were those people. In building vote by mail, they had the space to address all the concerns seriously. Their ability to do that helped strengthen trust in Oregon’s system. But in this political climate, the president or party leaders are going to drown out election officials.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21912736/AP_20237550455882.jpg) Andrew Selsky/AP

Andrew Selsky/APAdam Bonica, an associate politics professor at Stanford University, told me it’s a little like a surgeon who has developed a safe and effective procedure, and right when they’re about to perform it, someone rushes the room and tackles them. “2020 is not about whether vote by mail works as a system,” he said. “It’s about whether vote by mail can work when there’s basically an anti-democratic regime pushing against that.”

It sounds bleak, but it doesn’t have to be. Vote-by-mail advocates also note that this election could actually help more voters understand, Hey, there might be a better way. Voting experts say the best electoral systems are the ones that give voters lots of options — ways to vote early, in as many ways as possible.

That really is the lesson of vote by mail. Bruce Riley, the retired sheriff in Linn County, Oregon, and the son of Del Riley, the county clerk who took a chance on vote by mail almost four decades ago, told me that his dad, a World War II veteran, wanted to try it because he believed so much in public service. Part of that service was getting people involved in the democratic process. “I truly believe it was about trying to get more people involved in the democracy that we all take for granted in America,” he told me.

This has always been America’s contradiction: a democracy that struggles to be truly democratic. The bitter politics of this presidential election make it unlikely to happen in this year, and maybe not anytime soon.

But proponents of vote by mail see it as a way to get a little bit closer to that ideal. “Do we want government by and for the people or by and for the few and powerful?” Sen. Merkley told me. “And if you want government by and for the people, the vision of our Constitution, then vote by mail is a high integrity system that stops so many forms of voter suppression and intimidation and people are going to really like it.”

Druckenmiller understands people still think vote by mail is crazy or a terrible idea. Maybe he even relishes the critics, since he was once among them. But now, he says, if you don’t believe him, come down to Linn County, Oregon. Come see the revolution for yourself.

Will you help keep Vox free for all?

The United States is in the middle of one of the most consequential presidential elections of our lifetimes. It’s essential that all Americans are able to access clear, concise information on what the outcome of the election could mean for their lives, and the lives of their families and communities. That is our mission at Vox. But our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources. Even when the economy and the news advertising market recovers, your support will be a critical part of sustaining our resource-intensive work. If you have already contributed, thank you. If you haven’t, please consider helping everyone understand this presidential election: Contribute today from as little as $3.

Author: Jen Kirby

Read More