The dangerous delta variant is spreading. The future of schools is unclear. And millions of workers are about to be kicked off unemployment.

Sean thought he’d be back to work by now. Over the summer, the cafe where he worked before the pandemic reached out, saying he could have his old job back by early September. The cafe was located on a tech company’s campus in California, and his former boss wanted to staff up as office employees started coming in. (Sean spoke to Vox on the condition that his identity and that of his employer remain anonymous.)

It looked like his return to work would coincide pretty nicely with the wind-down of the unemployment insurance he’d been relying on to get by. “Everything was going fine,” he says — until it wasn’t. In mid-August, the cafe told him they wouldn’t need him back after all. “Due to the delta surge, the campus was completely closed again with no solid date for starting the process again,” he explains. “There’s a chance I get contacted in the fall, but my gut tells me it’s a done deal until next year.”

Like many workers relying on unemployment, Sean is hoping Covid-related unemployment benefits will be extended through the end of the year so he can find some time to devise a plan B, especially given that the delta variant is changing so many businesses’ plans. But that scenario is extremely unlikely. On Labor Day, expanded unemployment benefits put in place in response to the pandemic are set to expire, and there’s virtually no political appetite in Washington to extend them.

“The Biden administration has not made it a priority, and outside of [Democratic Sen.] Ron Wyden, you haven’t heard too many people in the Senate be willing to push on that,” said Andrew Stettner, a senior fellow at the Century Foundation, a liberal think tank. “It doesn’t seem like right now there would even be 50 votes in the Senate.”

That means that the extra $300 per week in federal employment benefits in place since December 2020 will end, as will programs aimed at people who wouldn’t normally qualify for unemployment insurance, such as freelancers, gig workers, and the long-term unemployed, which were put in place in the spring of 2020. Stettner estimates 7.5 million workers will lose all their benefits. Those who still qualify will only get what comes from states.

In a letter to leaders in Congress last week, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Labor Secretary Marty Walsh said they believe that cutting off the extra $300 is “appropriate.” They added that the White House thinks states can use remaining money from stimulus funds to help support some workers (namely, the workers who don’t normally qualify). But it’s not clear how many states are going to take that up. More than half have already cut off expanded unemployment benefits over the summer.

“There will be a few extended benefits programs, but for the most part, there’s going to be nothing available,” Stettner said. He added that, gleaning from his early talks with states, most are not in a position to deliver anything with remaining stimulus dollars.

America’s jobs situation is certainly improving, with 20 million people receiving some sort of unemployment compensation in February 2021 compared to around 12 million right now. And according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, there were 10 million job openings across the country as of June.

Still, there are questions about what the impact of cutting off expanded benefits now will be. Expanded unemployment programs have helped people avert economic disaster over the past 18 months, and it’s not clear what damage might be ahead. The dangerous delta variant is spreading and hitting many parts of the country hard. Hopes that the fall would bring more of a return to normal are fading. Some schools have already started to pause in-person learning or switch to hybrid models, and some parents still prefer to keep their kids home instead of in the classroom or in child care centers out of safety concerns. Return-to-the-office plans for many businesses are still in flux. Come early September, the people still out of a job aren’t going to be able to snap their fingers and land back at work.

That’s certainly the case for Sean, whose hospitality job was unavoidably altered by the pandemic. He acknowledges this has happened to thousands of others as well. “It seems the line of work I was in, as well as thousands of other hospitality cooks, chefs, etc., has completely ceased to exist with the transition to work from home,” he says.

7.5 million people is a lot of people to cut off from unemployment insurance all at once

When the pandemic hit in early 2020, shutdowns meant millions of workers were laid off or furloughed seemingly overnight, and by no fault of their own. Since then, unemployment insurance has made a meaningful difference in helping those people maintain some sort of economic stability, along with other stimulus programs. But expanded unemployment insurance has also been controversial: Many Republicans, business groups, and even some Democrats have argued that it’s too much and is keeping people out of work. And as the economy has recovered, that argument has only gotten louder as some contingents hold that generous benefits are causing a labor shortage.

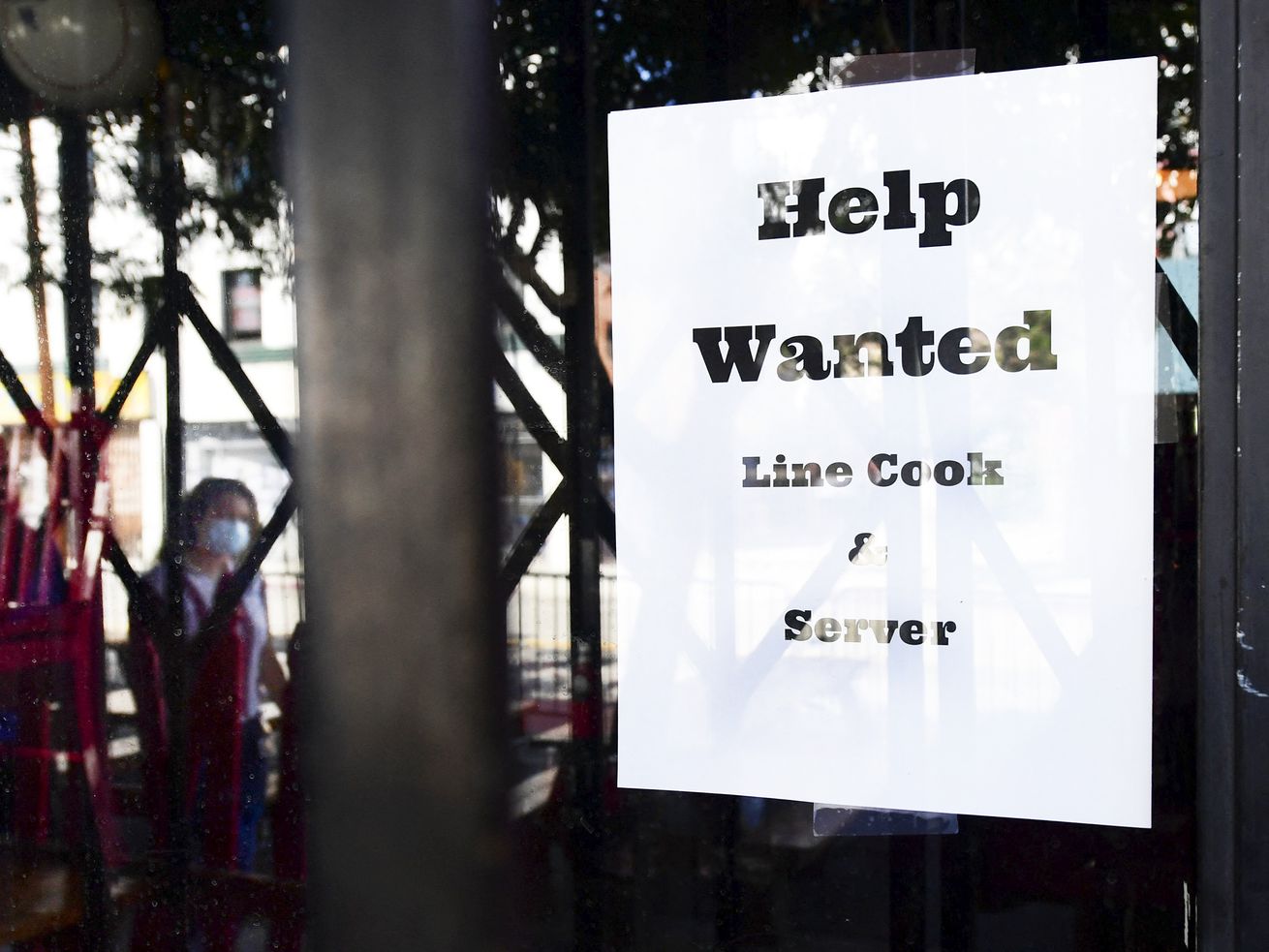

It is true that some workers are staying on the sidelines — in many parts of the country, it feels like there are “Help Wanted” signs everywhere, and business owners are complaining about not being able to find employees. But what’s not clear is exactly what is causing this; it’s likely a range of factors.

Peter Ganong, a public policy professor at the University of Chicago who has studied the potential disincentive effects of expanded unemployment insurance through the spring of 2021, said that more benefits are having somewhat of an impact, but not a big one. “Only a very small fraction of the number of jobs we need to get back to the pre-pandemic level or trend reflect the unemployment insurance disincentive effect,” he said.

new results on the effect of UI supplements on job-finding

2 designs x 2 policy changes yield consistent pattern: small, precisely estimated disincentive effects

Disincentive remains small even after job openings up pic.twitter.com/SsUHCHQddj

— Peter Ganong (@p_ganong) July 29, 2021

Among states that cut off expanded benefits early over the summer (26 in total, all but one Republican-led), the move doesn’t appear to have significantly contributed to job growth, though economists continue to debate what will happen going forward. New research released in August, first reported on by the New York Times, found that states ending benefits early didn’t meaningfully boost employment but did slash spending — a sign that it’s detrimental to workers and, potentially, the broader economy. The study found that for every eight workers who lost benefits, one found a new job. Meanwhile, it estimates that workers lost $278 a week in benefits on average but gained just $14 a week in earnings. Their spending fell by $145 a week. In the 19 states analyzed, that translates to a $2 billion drop in spending and a $270 million increase in earnings.

More people are likely to reenter the workforce over the weeks and months to come, as they have in previous months and weeks. But the transition won’t be guaranteed or easy. Some workers are struggling to find jobs that match their skills and aren’t positioned to take just any job, or they’re older, or they don’t have the credentials required for certain positions, or, for whatever reason, they’re just not getting a call back.

Sean, who has a degree in creative writing, has never been able to find a full-time position using that credential. Per California’s requirements, he has been applying for at least three jobs a week since July (even though he planned to go back to his prior employer until recently). He says he hasn’t gotten a single reply. “I have done a dozen or so skill assessments along with the applications, and I’m not hearing anything,” he says.

Workers really don’t know what the fall will bring

When President Joe Biden signed the American Rescue Plan in the spring, the White House and lawmakers rather arbitrarily anticipated that it would be appropriate for unemployment benefits to end on September 6. They didn’t anticipate some of the current challenges workers are facing, including the delta variant and an uncertain scenario for schools, that might render this a bad time to push the unemployed off a cliff.

There are myriad reasons people may not be able to return to work right now, or may be more hesitant to go back. Covid-19 cases and deaths are on the rise again. While the vaccines are available, many people are still nervous to get back out there.

Whether offices will reopen or businesses will close back down is uncertain. Some events are already being canceled, and offices are extending remote work, both of which have important implications for many jobs. Workers in the live events space expecting that work to come back might need to figure out if it’s time for them to change careers altogether instead of continuing to wait it out. Businesses in areas where there used to be a lot of office workers may not need to hire as many employees back soon, or ever.

Child care and elder care remain a challenge for many families. It’s not clear whether schools and day cares will go back to in-person learning and stay that way, meaning a parent may need to stay home. Families may also be hesitant about older parents staying in assisted living facilities and opt to move them home, another care burden.

“For parents, and especially mothers, the ability to go back to work just isn’t there right now. Schools at this point seem to be planning to open, but the minute we see things are bad and kids are getting sick, then things may change again,” said Julie Kashen, a senior fellow and director for women’s economic justice at the Century Foundation. “We don’t know what the fall is going to bring, but we do know it’s not going to bring a full recovery that suggests people don’t still need support.”

Once benefits are cut off, and if people aren’t able to find work, that can do significant harm to their finances and their lives. As the aforementioned research shows, it may also be detrimental to the economy, because people who don’t have money coming in also don’t have money to spend.

“If you’re saying, ‘I’m just going to shut off your benefits,’ but I still don’t have child care, and I still don’t have a way to ensure my child is attending their digital school, how is that going to force me into the labor market?” Rebecca Dixon, executive director of the National Employment Law Project (NELP), told Vox earlier this year. “It may force me into homelessness. It may force me to be hungry. There’s an enormous number of workers that are still behind on rent. This whole narrative is just completely wrong, and it’s incomplete.”

America needs to have a bigger conversation about unemployment insurance

“The anti-poverty response to the pandemic has been really dramatic, unlike anything we’ve ever done before. We’ve done a much better job of ensuring income risk from unemployment,” Ganong said. What that will mean down the road — especially as benefits are shut off — is up in the air. The Labor Department is upping investments in grants to help train some workers, which could help more people find something new. But workers have also found it difficult to decipher whether they need to switch jobs or not.

Apart from what happens in the immediate term, there is one bigger issue in play here: America’s unemployment insurance system needs to be reformed. It’s run as a federal-state program that leaves states with a lot of leeway as to how much assistance to provide workers, what parameters to put in place, and how easy or difficult to make accessing benefits. Many Americans saw firsthand when the pandemic hit just how hard the system is to navigate.

Congress has been guessing at how long expanded unemployment insurance will be needed from the outset of the Covid-19 outbreak. At the outset of the pandemic, President Donald Trump signed a bill putting in place $600 a week in extra federal unemployment benefits, which expired in July 2020. Then lawmakers added an extra $300 in benefits in December, which were extended under Biden. Now both the extra money and the expanded programs are supposed to wrap on Labor Day.

Given the current scenario, reasonable minds could question whether conditions are right to cut people off. Lawmakers could try to put in place conditions to better automate unemployment benefits so that it’s based not on political whims but on the actual health and economic situation on the ground. They could also strengthen minimums required of states so that an unemployed worker in Mississippi isn’t positioned much worse than someone in Massachusetts.

There have been some rumblings from progressives about the possibility of pushing for another extension of pandemic unemployment benefits, but many on the Hill believe that at this point, it’s really a nonstarter. “We don’t have the votes in the caucus for an extension,” one Democratic aide told Vox in an email.

Biden has urged Congress to take up unemployment insurance reforms as part of its upcoming budget reconciliation process, an agenda that he wants to include fraud prevention, equitable access, and adequate support. Those types of measures would make a real difference in the future, but they won’t help workers like Sean, who are being harmed by the cutoff right now. “Safety is really important in all of this, and I’m not mad at the company at all, no harsh feelings whatsoever,” Sean says. “I’m just frustrated by the situation as a whole.”

Author: Emily Stewart

Read More