And the rest of the week’s best writing on books and related subjects.

Welcome to Vox’s weekly book link roundup, a curated selection of the internet’s best writing on books and related subjects. Here’s the best the web has to offer for the week of March 1, 2020.

Beloveds, it has been a week in publishing. Where to start, even?

- One may as well begin with the Hachette walkout. At Slate, an anonymous employee explains why she joined her colleagues in walking out Thursday afternoon, after the company announced that it would publish Woody Allen’s memoir — which ultimately led to Hachette canceling the book:

Usually for an acquisition for a celebrity memoir that isn’t written by someone as deeply problematic and terrible, [we would know] as soon as the contract was signed. It’s exciting when you get any other celebrity who hasn’t done terrible, awful things, you want to tell everybody: “We bought their memoir. We’re publishing it and we just signed a contract. Stay tuned next year because you’re going to be able to buy it.” Because why wouldn’t you want to announce this amazing thing that you just bought that your readers are going to get to have? Obviously, they must’ve known that they were doing something wrong, because they didn’t tell anybody when it was acquired.

- Meanwhile, ViacomCBS announced plans to sell Simon & Schuster, reports Publishers Weekly. The most likely outcome is that another of the Big Five publishing houses will acquire Simon & Schuster for itself, bringing the industry down to the Big Four. For a close look at how publishing’s ongoing consolidation is hurting everyone except for those at the very top, I’ll direct you to my December article on what happened to e-books in the 2010s.

- And the American Dirt saga continues! At Publishers Weekly, Claire Kirch reports on Oprah’s summit for Apple TV+ over the controversy:

Making no secret of her enthusiasm for American Dirt, Winfrey told Cummins that she had “succeeded in being a bridge, there’s a swell of people who love the book” before introducing three Latinx authors who did not love the book: Reyna Grande, Julissa Arce, and Esther Cepeda. While the three have written critiques of American Dirt that were published in different publications, they reserved their harshest words on the show for the book publishing industry – two representatives of which sat in the front row: Macmillan president Don Weisberg and Cummins’ editor at Flatiron, Amy Einhorn, who now heads Henry Holt.

“My issue is not with Jeanine’s book,” Arce said, “my issue is with the publishing industry that systematically silences us, that’s keeping us off the bookshelves.”

- At VQR Online, Joshua Wolf Shenk considers Joan Didion, Los Angeles, and alienation. (Am I recommending this to you because he cites me on Didion? Listen, I’m not not doing that.)

On the page, Didion exhibits the epitome of control, mastery, and clarity. Naturally, this order proceeds from a chronic sense of meaninglessness, detachment, and distress, which always, with Didion, swallows up any longing for respite. In readers, this excites a wild desire, one that is, by definition, insatiable, and I think this accounts for her popularity, and for the fundamental inability of the critical class to read her accurately, despite her ongoing protestations.

- At LitHub, Alana Mohamed makes the argument that J. Edgar Hoover learned everything he knew about hiding information from his time at the Library of Congress:

In fact, Hoover was not omniscient, but the next best thing: a librarian with an extensive card catalog. While librarians are often cheered for democratizing knowledge, controlling information is the underlying tenet of the profession—which is partially why the profession today is largely categorized within information sciences. Hoover understood this from the time he joined the Library of Congress as a clerk, his first job in Washington, in 1913. He created catalog cards for the collection, which was then a novel way of organizing libraries. This experience would later help him to index thousands of citizens he deemed radicals, as well as obfuscate evidence to avoid accountability. Hoover’s methods of manipulating information represents all that can go wrong when the principles of librarianship are used to combat public good.

- At Mental Floss, Tony Dunnell has a list of 18 surprising things that have been stolen from libraries:

In 2017, the Adelaide City Library was hosting a traveling exhibition by the Australian Orthopaedic Association. It’s fair to say no one was expecting a heist. However, the exhibition was infiltrated by a group of three men pretending to be council workers. Their target, for reasons unknown, was a fiberglass skeleton with a street value of about $300 USD. The men were caught on CCTV cameras casually walking out of the library and then boarding a bus, accompanied by the skeleton. No one was ever arrested for the crime.

- It is so, so, so hard to write good journalistic criticism of poetry. Whenever I try, I always find myself just putting stanzas in block quotes and gesturing, like, “Isn’t this cool?” At the New York Times, Elisa Gabbert shows us all how it’s done in her review of Alice Notley’s new book For the Ride:

Really great poetry is difficult to read. I don’t just mean it’s challenging, though it usually is. I mean it’s hard to make progress, because the density of meaning in the language stops you; it makes you read in loops. Alice Fulton has called poetry “recursive”: “It sends you back up the page as much as it sends you forward.” Because of this effect, it once took me all afternoon to finish reading John Ashbery’s long poem “Self-Portrait in a Convex Mirror” — I kept wanting to stop and start over again. Alice Notley’s best work feels this way: intensely recursive, almost too good to read. In its semantic density, great poetry gives you the sense you’ve skipped over and missed some available shade of meaning. You certainly have.

- Speaking of NYT book criticism, Parul Sehgal has long been my fave on their roster. She participated in The Cut’s How I Get It Done series this week, and now I know how she can be so smart: She just never sleeps.

I usually go to bed around 3 or 4 a.m. I have a 3-year-old daughter, so I need those unbroken hours to trick myself into thinking and reading. My husband handles the morning with my daughter. I emerge after about five hours of sleep, like a character stumbling onstage in a Eugene O’Neill play. There are simmering resentments and tantrums and dance parties.

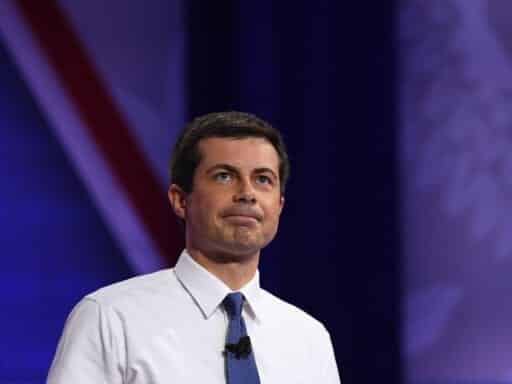

- Pete Buttigieg’s favorite author is the Norwegian writer Erlend Loe. At Jacobin, Ellen Engelstad argues that Loe hates people like Buttigieg:

But there’s something even funnier about this literary passion. In recent years, Loe’s works have moved from something that might understandably appeal to Pete, to an outright attack on him and his base. And maybe Buttigieg’s fascination for Naïve. Super and Erlend Loe in the early 2000s tells us something interesting. For while Pete, who dropped out of the presidential race just yesterday, is still caught up in the naive liberalism and optimism that surrounded the “end of history,” the world around him has moved on.

- At Electric Lit, Sara Fredman introduces us to Margery Kempe, the medieval mother of 14 who probably invented the memoir:

Margery’s Book offers perhaps the earliest example of how childbirth and motherhood can become generative in a literary context—even, or perhaps especially, when the writing is not about childbirth and motherhood. We need all the examples we can get. I am, I’m sure, one among many women writers who look to established women authors as guideposts. We scour interviews like detectives, hoping to gather clues about what it takes to turn the ideas in our heads into bound books with our names on them. That’s why comments like Lucy Ellmann’s in The Guardian—“You watch people get pregnant and know they’ll be emotionally and intellectually absent for 20 years”—are a punch in the gut.

- At Slate, Rebecca Onion talks to economic historian Eli Cook about how the Choose Your Own Adventure books reflect ’80s-style capitalism:

I don’t usually write about Choose Your Own Adventure [laughs]—what I usually write about is the history of economic thought. Anyone who studies economists like Milton Friedman and other neoliberal economists who exploded in popularity around that time knows that for them choice is everything, it’s the only thing. The world is just individuals floating around, in an ahistorical space. Reading this, I’m like, “Oh my God, it’s like Milton Friedman for kids.”

- But also at Slate, Rebecca Christie warns us dolefully of the dangers of reading politics into children’s literature, citing the long debate over whether If You Give a Mouse a Cookie is secretly critiquing the welfare state:

Most of the moralizing linked to If You Give a Mouse a Cookie is adults talking to other adults, many of whom have never even read it. This seems an unfair burden to put on a children’s book, which already has a job to do. Adults do need to read kids’ books with an eye toward society. It’s a travesty that so many classics default to all-male environments, and so that many of the books that are about women and people of color focus primarily on their struggles. But when it comes to the mouse and the cookie, adults who focus on politics rather than the adventure are just getting it wrong.

- But some children’s books are definitely political — like the 1938 Nazi propaganda children’s book called The Poisoned Mushroom that Amazon just had to pull from its listings, reports Forbes.

- China’s bookstore business has been booming in recent years. But now the coronavirus is endangering independent bookstores, reports Kenrick Davis at the Sixth Tone. (For the shallow among us, by which I mean me: This story has some truly stunning photography of Chinese bookstores.)

- You know what coronavirus has been great for, though? Books about epidemics, according to the Guardian. I know everyone’s going for Station Eleven right now, but I’d recommend Ling Ma’s novel Severance.

- This is so satisfying to watch: Penguin Teen’s social media team is playing book dominoes on TikTok. At Publishers Weekly, the team explains how it set up the game.

@penguin_teen Pls don’t let this flop it’s a miracle i still have a job #foryou #fyp #fy #dominos #books #officelife #viral

And here’s the week in books at Vox:

- Woody Allen got a book deal. Staff at his new publisher have walked out in protest.

- Woody Allen’s publisher canceled his memoir after staff walked out

- If God is dead, then … socialism?

- Reading Lolita in the wake of the My Dark Vanessa controversy.

As always, you can keep up with all our books coverage by visiting vox.com/books. Happy reading!

Author: Constance Grady

Read More