“The most transformative presidents in our nation’s history — Lincoln, FDR, LBJ — were not ideologues.”

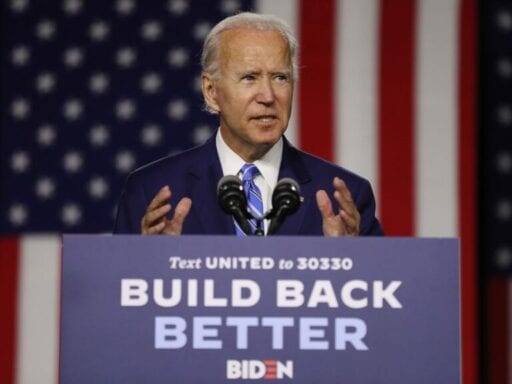

Progressive groups overwhelmingly favored confrontational leftists like Bernie Sanders or Elizabeth Warren during the 2020 primary campaign. And many pretty clearly favored younger, more diverse rising stars like Kamala Harris and Pete Buttigieg over Joe Biden. Biden, after all, is not only a paid-up member of the “establishment,” he’s a veteran of the long shadow cast over American politics by Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan — a guy who voted in favor of the invasion of Iraq, of multiple pieces of legislation deregulating the banking industry, of the 1994 welfare reform bill, and of the “tough on crime” 1994 criminal justice bill.

Biden is now the presumptive nominee, but progressives still fundamentally do not see him or his team as kindred spirits. Many, however, are becoming more optimistic about Bidenism. His platform is in many ways a surprisingly progressive approach to policy that the left sees as a triumph of their own work in trying to change the terms of debate in American politics.

Biden “envisions a massive public sector role for job creation,” points out Faiz Shakir, who managed Bernie Sanders’s 2016 campaign. He doesn’t think Biden has suddenly become a left-wing hero. But he credits Biden, Biden’s team, and mainstream Democrats more broadly with “understanding that in Covid times there needs to be thinking about bold practical measures.”

Republicans have so far failed in their attempt to convince moderate voters that Biden is a socialist snake in the grass. Even as broader American society sees a genuine upsurge of left-wing radicalism both in the streets and in the realm of ideas, public perception of Biden continues to hold that he is closer to the middle ground than President Donald Trump.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20095492/200710_ideology_candidates_fullwidth.png)

Republicans have been reduced to trying to argue that Biden is just a Trojan horse for other far more left-wing figures in the party. But it’s an argument that founders since Americans just watched Biden win an extended primary campaign in which he was repeatedly assailed for failing to meet various progressive litmus tests.

Biden won the primary handily by convincingly slapping a moderate label on a policy agenda that is nonetheless far bolder than the one pursued by Barack Obama or proposed by Hillary Clinton in 2016.

“That’s his genius now,” one pillar of the Democratic establishment who’d initially preferred several younger candidates from the moderate lane told me.

The Overton window, explained

Biden is not progressives’ champion: He does not push the envelope in the ways that they want, and he has not endorsed their most ambitious ideas. But public opinion has been shifting leftward, and Biden’s thinking has shifted with it, creating a platform that progressives are genuinely excited about.

It’s “the most progressive platform of any Democratic nominee in the modern history of the party,” Waleed Shahid, communications director for Justice Democrats, a group famous (or infamous) for backing left-wing challengers to incumbent congressional Democrats, tells me.

They also see his approach as a triumph of sorts in changing the scope of what is acceptable to discuss in national politics. The “Overton window” came up repeatedly. The idea is that at any given time, only a certain set of ideas is deemed worthy of mainstream discussion, and where the contours of that window are located has meaningful impact on political outcomes. Ideas like Medicare-for-all, a Green New Deal, defunding the police, and wealth taxation did not win in the primary, but they did establish significant beachheads in public consciousness and contribute to an environment in which Biden’s very ambitious agenda can be seen as moderate.

Biden, says Shakir, “is not leading the Overton window movement, but he’s also not disregarding or moving against it.”

Shahid observes that “the most transformative presidents in our nation’s history — Lincoln, FDR, LBJ — were not ideologues fully aligned with the most radical movements of their time.” Instead, they at times worked with activists to move the ball forward and at other times trimmed their sails to meet the constraints of public opinion.

Biden threads the needle on police reform

Police reform, a topic that was not at the forefront of the public agenda during the primary, is nonetheless a spot-on case study in how Biden threads the needle between an increasingly influential left and an unpopular incumbent president.

The mass public has grown considerably more skeptical of American policing over the past four years according to a Pew survey released last week. In contrast to the prevailing attitudes of 2016, most Americans now say the police do a poor job of calibrating their use of force appropriately to the situation, that they do a poor job of treating all racial groups equally, and that they a poor job of holding themselves accountable when misconduct occurs. That creates a public mood that is now favorable to many reform ideas Biden has embraced like curbing qualified immunity, conditioning federal police funding on new training and diversity initiatives, and reinvigorating federal oversight of police departments.

What left-wing activists want Biden and other politicians to do, however, is defund the police, an idea that Biden does not support. The window of discussion has shifted left, and Biden sits squarely in the middle of it — a onetime champion of “tough on crime” politics who’s now backing a once-unthinkable list of reform demands.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20080693/PP_2020_1.07.09_qualified_immunity_0_11.png)

He’s helped in staking out this ground because policing issues have in some ways become less racially divisive inside the Democratic Party coalition.

“Overwhelming shares of Democrats of all races support reforms,” Jocelyn Kiley, the associate director of research at Pew, tells me. And when it comes to cutting police funding, the idea is popular with younger Democrats but unpopular overall, and that’s true across racial groups. “By and large, that support is equally high among white Democrats as it is among Black and Hispanic [Democrats].”

Kiley helped me break down the numbers in a different way and explains that among Democrats, 43 percent of whites, 42 percent of African Americans, and 32 percent of Hispanics want to see cuts, with the rest preferring either flat or increased funding. Indeed, increasing police spending is more popular with Black and Hispanic Democrats than with white ones.

But as my colleague Aaron Ross Coleman writes, a narrow focus on police funding ignores an important point: “Black people view poor policing as an aspect of a broader state failure to provide adequate public goods and services.” And that’s where the progressive side of Biden’s agenda shines through.

Biden is proposing a substantial expansion of the welfare state

While Trump would clearly like to ride a white backlash against Black Lives Matter to reelection, in reality he has ceded the middle ground in the culture war to Biden. Trump is refusing to acknowledge any need for change. Biden eschews a unpopular headline demand while embracing reform proposals that activists do like and the mass public is now willing to listen to. And he can get away with it with his base of working-class African Americans in part because when it comes to the public investment side of the ledger, Biden is squarely there, especially with regard to low-income communities.

Indeed, as Ezra Klein and Roge Karma wrote in December, the bdynamic of the 2020 primary was that on economic policy, “by the standards of the Democratic Party in 2008, the moderates look like leftists.”

- Biden wants to quadruple federal spending on low-income housing assistance.

- He is proposing to triple federal spending on low-income K-12 schools.

- He wants to double Pell Grants and make community college free.

- Separately from the housing assistance money, he’s calling for a $100 billion investment in an affordable housing trust fund.

- His transportation platform includes a $10 billion special set-aside for transit projects in high-poverty areas.

Then on health care, especially as modified by the joint task force with Bernie Sanders, Biden’s plans are more aggressive than they sound, featuring a Medicare-administered public option that, as Ella Nilsen explains, “would cover a range of people, including low-income Americans who are not eligible for Medicaid, and anyone who elects to choose the public option from the Affordable Care Act exchanges. Those who currently get health insurance from their employers would also be eligible.”

Biden’s health plan also features the extremely mundane-sounding idea of switching the ACA subsidy formula to be pegged to the price of a gold plan rather than a silver plan. This means, basically, extra money for every family earning less than 400 percent of the poverty line. (Biden has also pledged to lift the subsidy cap for people earning more than that.)

This is all a formally race-neutral agenda, but given the realities of American economic life, it amounts to not just a game changer for low-income households but a significant blow to the systemic economic gaps between Black and white Americans.

Shakir, who managed Bernie Sanders’s campaign, says the Biden agenda is strikingly progressive on these points not despite Biden’s moderate profile but because of it.

Biden “starts with a politics of what’s possible at a particular moment and time,” he says, and the broad consensus in the Democratic Party is that what’s possible has changed.

Shahid uses the same analogy: “Progressives often shift the Overton window and the establishment steps through the door a few years later ($15 minimum wage is a good example), while the left moves on to other policies.”

Playing to win on climate change

The task force process probably scored its biggest win for the left on the subject of climate change, where a group co-chaired by John Kerry and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez accelerated the pace at which Biden calls for electricity to be 100 percent carbon-free.

Today the 6 Biden-Sanders Unity Task Forces are unveiling final language.

The Climate Task Force accomplished a great deal. It was an honor to serve as co-chair w/ Sec. @JohnKerry.

Among the notable gains: we shaved *15 years* off Biden’s previous target for 100% clean energy. https://t.co/pnLj7uufeg

— Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (@AOC) July 8, 2020

Varshini Prakash, the co-chair of the Sunrise Movement, hailed the outcome of the process, saying that “we now have a Democratic unity position that begins to reflect what young people have been shouting relentlessly — that the climate crisis is not some far off threat.”

Sealing the deal here was eased somewhat by the unique dynamics of the climate issue. On health care, the left-coded position involves replacing existing private insurance with a government-funded program, which requires broad-based tax increases that make moderate Democrats wary. On climate, by contrast, the longstanding dynamic has been that moderates want to focus climate efforts on carbon pricing (which is to say, an unpopular broad-based tax increase), while the left derides this as neoliberalism and calls for a more command-and-control approach.

Biden is a decidedly moderate politician but less of a wonkish technocrat type than Obama was, so he’s happy to deemphasize a politically unpopular moderate idea. Instead, task force proposals (like earlier work from House Democrats on forging a party consensus) focus on the stick of regulation and the carrot of massive public investment (both of which generally poll well) while avoiding calls from climate activists for bans on fracking and nuclear power that alienated labor unions and some moderates.

Here, as on health, poverty, and police reform, Biden is essentially stepping into the sweet spot of the Overton window, and activists are happy with the result. The same could be true on immigration if the stars align correctly, but it also could turn into the difficult exception to the rule.

A tale of two immigration plans

Of course, not everything works out so neatly. On the immigration disputes that have at times defined Trump-era politics, the three-way tug-of-war among activist demands, public opinion, and the institutional realities of American government are complicated.

On an aspirational level, Biden’s immigration plan takes the core Obama-era concept of a path to citizenship for the long-settled and otherwise law-abiding unauthorized immigrant population and runs with it. While the “Gang of 8” legislation that Obama championed paired that idea with huge investments in more stringent border enforcement, Biden’s current proposals don’t take that direction. Instead, they entail a forthright expansion of legal immigration by eliminating certain caps on green card issuance.

This would have been a risky political stance in Obama’s day, but Gallup recently reported that for the first time on record, more Americans favor increasing rather than decreasing immigration flows.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/20083631/Screen_Shot_2020_07_14_at_3.35.49_PM.png)

If Democrats score a huge landslide win, picking up many Senate seats, and then contrive to end the filibuster, it’s possible that something like this — perhaps incorporating some enforcement ideas progressives don’t like or limiting the ambitions somewhat — will happen and it will all go according to plan.

But if not, Biden is going to be stuck in the much more treacherous situation of presiding over an immigration enforcement apparatus that’s been taken with the mission of deporting a population that, theoretically, Democrats believe should be legalized and set on a path to citizenship.

“The big thing to remember is that Obama was not universally loved among immigration advocates,” says Aaron Reichlin-Melnick, a policy counsel at the American Immigration Council, but activists “pushed him in his second term into becoming a lot more lenient on some issues of immigration.”

That pivot from being the “deporter-in-chief” who set a record for removals that Trump has not yet matched to attempting a sweeping series of executive actions to bestow formal protection from deportation on millions of people involved a long series of tough battles.

The Obama administration tried, fitfully, to push the immigration enforcement apparatus to exercise more discretion in whom it targeted — facing both a lot of internal pushback from front-line US attorneys and immigration agents and a lot of blowback from advocates who said he wasn’t meeting his commitments. Trump has very much thrown the levers in the opposite direction, and reversing course in a substantive way will involve taking on some in-the-weeds battles.

Reichlin-Melnick predicts that when it comes to staffing DHS and DOJ and actually implementing policy, there’s going to be “a fight between making symbolic changes and making systemic changes.”

Similarly, Biden has formally committed to not just rolling back the cruelest aspects of Trump’s clamp-down on asylum but to generally walking away from the deterrence-oriented approach that Obama took as well. That’s easy to say in private meetings with activists or even around a policy task force negotiating table that also features a half-dozen higher-profile issues.

But immigration activists have real doubts as to whether Biden would stick with that plan if i arrivals start surging again, and cautious politicos have real doubts as to whether it would be wise to do so. On enforcement topics in general, the left has won a lot of elite battles inside the Democratic Party, but it’s less clear how much the larger window of public opinion has really shifted or how much those newfound views will hold together without Trump as a foil.

Personnel is policy

The practical functioning of the American government is never so neat and tidy as a bunch of plans on a piece of paper. Contemporary administrations do what they can through the legislative process and then fall back on controlling the machinery of the administrative state. And here, as Elizabeth Warren (quoting Reagan-era conservatives) likes to say, the key point is that “personnel is policy.”

You can love Bidenism without loving Joe Biden, but when legislative dealmaking breaks down and it becomes incredibly relevant who holds which sub-Cabinet jobs, the personal identity of the Biden team becomes a much bigger deal. That’s why many progressives have become so invested in pushing Warren as a VP option — they’d like her Rolodex as close to the West Wing as possible.

Biden’s transition team, though still skeletal at this point, is encouraging to the left; it’s headed by Ted Kaufman, who is probably the most progressive member of the true Biden inner circle. But that inner circle also includes Bruce Reed, a longtime bête noir of the progressive wing of the Democratic Party, and is generally (as you would expect) a very establishment-oriented group of people.

Realistically, an administration led by Barack Obama’s vice president is going to feature a lot of personnel continuity with the Obama administration, whether the left likes it or not. The establishment’s own views have, however, shifted considerably to the left over the past 15 years, in part as a result of changes in the objective environment and in part because of shifts in public opinion.

In that sense, moderate Joe is nobody’s Trojan horse. But it’s still the case that when you peek at what’s inside, it’s a much more transformative agenda than a superficial glance at the outcome of the primaries would lead you to believe.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Matthew Yglesias

Read More