Movement conservatism has left Sen. Romney behind.

Some Never Trump conservatives and liberals hope that Sen. Mitt Romney is about to transition from a lonely Donald Trump critic to the leader of a movement to get Republicans in Congress to turn on the president.

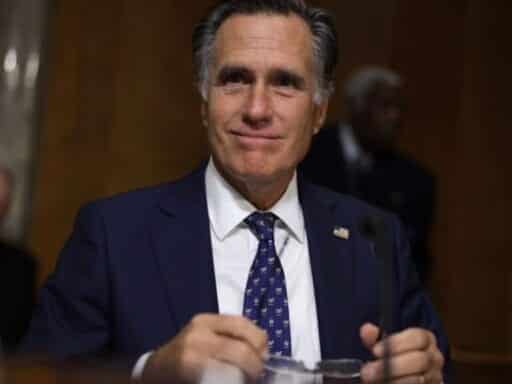

The senator and former presidential candidate has become the most prominent opponent of Trump’s agenda inside Washington — prominent enough to be personally attacked by the president on Twitter multiple times (including calls for his improbable impeachment), prominent enough to be listed among the liberal critics of the president who Donald Trump Jr. would like readers to send copies of his new book.

Romney has been outwardly critical of Trump on Ukraine, specifically, tweeting, “By all appearance, the President’s brazen and unprecedented appeal to China and to Ukraine to investigate Joe Biden is wrong and appalling.”

And now Romney has gained a measure of “strange new respect” among media observers. Vanity Fair wrote that Romney was the “pressure point” for impeachment.

Meanwhile, some conservatives hope for the same. The Bulwark, a right-leaning publication that opposes Trump, published a piece titled “Mitt Romney to the Rescue?” An article for the Atlantic written by the executive director of Republicans for the Rule of Law said bluntly, “Mitt Romney, It’s Time,” arguing, “The senator is best positioned to pry the Republican Party from President Trump’s hands” because he’s not up for reelection until 2024. He’s also a Republican elected in a deep red state — so he does have a constituency.

But there’s a problem with these arguments: Many conservative voters were unenthused by what Romney was selling in his 2012 presidential bid and don’t appear to want it now, either. For voters on the right, Romney is a symbol of the establishment GOP they rejected in 2016 in favor of Trumpist populism. Romney is a wealthy blue blood who earned his money in private equity and is a former governor of a liberal state. He has a reputation for pragmatism that, to some conservatives, is seen as weakness.

For those looking to Romney to lead the charge against Trump in the Senate, or at least thwart him, it’s important to understand that he would begin at a distinct disadvantage. Not only would he need to change the hearts and minds of his fellow Republicans, he would need to grab hold of a conservative movement that has largely left him behind.

A man standing alone — really, really alone

First and foremost, Romney has decidedly not gained the ability to assemble a team of fellow travelers around him to stand united in opposition to Trump. Far from it; as conservative writer Varad Mehta noted in Arc Digital, Romney’s popularity is underwater in his home state of Utah (he has a 46-51 percent approval rating), but Trump’s popularity has remained remarkably static — and very high — within the GOP:

In their latest surveys, Gallup, CNN, and Quinnipiac all found only 6 percent of Republicans endorse removing President Trump from office, with 93, 90, and 91 percent, respectively, against. After peaking around 15 percent earlier this month, GOP support for impeachment in FiveThirtyEight’s tracker has dropped to 11 percent. If anything, Republican opposition is hardening.

Equally solid is Trump’s standing in the party. His job approval with Republicans is 83 percent in Quinnipiac, 87 percent in Gallup, and 90 percent in CNN. These numbers are not the making of an anti-Trump uprising by congressional Republicans.

On that front, the decision for congressional Republicans is an easy one, and the battle for the “soul” of the GOP has already ended: If the choice is between siding with an unpopular senator recently described by a former campaign volunteer as a “virtue-signaling headline-chaser” or a popular (at least within his party) president, they’ll take Trump. (Not least because the alternative might entail a damaging primary fight with a Trumpian challenger, in the vein of Kelli Ward or Katie Arrington.)

But the problem for Romney isn’t just about his standing among conservatives in comparison with Trump. The problem — newfound liberal interest notwithstanding — is that his conservative bona fides have always been somewhat up for debate. And that argument has largely been shaped by people other than Romney.

Romney was considered a real conservative — until he wasn’t

Back in the 2008 presidential cycle, when Romney won the Iowa straw poll before dropping out in February 2008, he had the support of conservative outlets like National Review and visible right-leaning pundits like Laura Ingraham and Rush Limbaugh, who said of Romney:

I think now, based on the way the campaign has shaken out, that there probably is a candidate on our side who does embody all three legs of the conservative stool, and that’s Romney. The three stools or the three legs of the stool are national security/foreign policy, the social conservatives, and the fiscal conservatives.

To some conservatives, it was John McCain who was the secret liberal, not Romney. One man interviewed by Reuters in 2008 said after Romney dropped out, “The only thing I can think to do is to vote for McCain (in November) and I am not voting for McCain because of his views.”

But others were suspicious, viewing Romney’s famous pragmatism as evidence that he wasn’t really one of them after all. As a right-leaning blogger who goes by KLSouth on Twitter wrote in a post in 2011:

Mitt Romney represents everything that is wrong with our party and everything that has left us dying in a ditch. Romney is a RINO. A progressive Republican. A pretend conservative. Pretend conservatives are what got us to where we are and are what will completely destroy us if allowed. Romney will be an exact repeat of John McCain.

And Limbaugh seemingly changed his mind on the former Massachusetts governor by 2011, saying of Romney:

“Romney is not a conservative. He’s not, folks. You can argue with me all day long on that, but he isn’t… What he has going for him is that he’s not Obama. This isn’t personal, not with what country faces and so forth. I like him very much. I’ve spent some social time with him. He’s a fine guy. He’s very nice gentleman. He is a gentleman. But he’s not a conservative.”

The thing is, nothing about Romney’s record had changed between 2008 and 2011. He was still the same Bain Capital founder and former Massachusetts governor noted for working across the aisle with Democrats (or as then-RedState writer Ben Howe put it, a pandering flip flopper who “does what gets him popular and earns him votes”) he was in 2008. Back then, conservative pundit Mark Levin wrote he shared “most of our conservative principles” and demanded conservatives get on board with Romney’s campaign.

As my colleague Matt Yglesias noted in a piece for ThinkProgress in 2011 on a critique of Romney published in National Review, “What’s strange about this editorial is that it involves NR pretending that somehow it’s Romney who’s changed since they endorsed him four years ago rather than conceding that they’ve simply changed their standards of what counts as conservative health policy.” (National Review’s editors argued that the Affordable Care Act “raised the stakes” for the health care debate, necessitating the critique.)

And little has changed about Romney since he lost in 2012 and, after nearly becoming secretary of state, decided to run for Senate. But a lot changed about conservative voters, what they want, and more importantly, who they want to vote for.

Romney is the victim of a changing conservative electorate that wants, well, not Romney

When Romney ran in 2012, he was encountering a GOP transformed — particularly after the Tea Party shifted the party to the right beginning in 2009.

I spoke with Jennifer Stefano, who first got involved with the Tea Party back in 2008 and is now vice president of the Commonwealth Foundation. She told me that the movement’s basic ethos is: “We want a limited government that respects the rights of the individuals over the state. We fought and still fight for economic freedom so all Americans can have opportunity, economic prosperity, independence and fairness from their government.”

Stefano added that in her view, much of the Tea Party’s activism was intended to be a rejection of Republican economic policies, not a response to Obama. “There was no chance that we were going to embrace Republican messaging,” she said. “We were furious at the bailouts that began under President George W. Bush, and many of us felt that the Republican Party betrayed what they were supposed to stand for, namely a limited government whose policies allow individuals the opportunity to flourish. Bailing out corporations with taxpayer money is antithetical to that.”

But the shift went deeper than the Tea Party. As detailed in Washington Post reporter Dan Balz’s book Collision 2012: Obama vs. Romney and the Future of Elections in America, the Tea Party revolution and the 2010 midterms “produced a party that, at its grassroots, was more militant in its beliefs and less willing to accept compromise from its leaders.” And Romney was — and is — many things, but militant is not among them. It was that militancy from grassroots conservatives that made blunders like Romney’s “47 percent” gaffe — referencing the number of Americans who don’t pay income tax — even more dangerous.

As National Review’s Rich Lowry argued at the time, such remarks “represent[ed] a backdoor return to country-club Republicanism.” But Romney himself fit that stereotype — not just of a country-club white shoe Republican, but of a Republican all too happy to glad-hand with Democrats like the late Sen. Ted Kennedy when it suited his purposes while simultaneously declaring himself to be “severely conservative.”

Romney was exactly the kind of Republican that, while once representative of the conservative brand, was anathema to many conservatives in 2012 — and in 2016. They didn’t want bipartisanship. They wanted, more or less, to punch Democrats in the face.

And that leads us to 2019, and a GOP electorate that, after losing in 2008 and 2012, finally has a pugilist in office. While Trump’s conservative bona fides have themselves been debated by right-leaning thinkers most of all, his ability to fight has not — and in a world in which, as Daily Wire editor at large Josh Hammer told me, conservatives believe they are “fundamentally under siege from the left,” a fighter is what the right wants.

A conservative pundit told me that in 2012, “Romney’s entire pitch was civility. He wasn’t particularly conservative in his record (see Romneycare) and was widely perceived to be middle-of-the-road on issues like abortion until the primaries. So the pitch was Inoffensive Republican 2.0 (John McCain was 1.0). After he lost, the specific kickback was on that civility pitch. Hence Trump.”

It’s not that Romney became a different kind of conservative from the one he was in 2008. It’s that conservative voters did. They’re more populist, and more suspicious of the machinations of big business. (It’s no wonder that Sen. Tom Cotton is demanding an investigation into WeWork.)

Adam Neumann ruined WeWork, yet walks away with $1.7 BILLION, while thousands of employees get laid off. Neumann is a fraud & a good example of why some people support a socialist like @BernieSanders. He ought to be sued & investigated. https://t.co/SvROFSFBcA

— Tom Cotton (@TomCottonAR) October 23, 2019

Mitt Romney? The Romney of Bain Capital and country-club Republicanism, someone who didn’t seem to get the base — and moreover, how mad the base was — back in 2012? That’s not the person conservative voters are looking for.

Romney is alone among Senate Republicans in his outspoken disapproval for Trump, but he’s alone among Republicans in other ways, too. He’s not a populist. He’s not a fighter. He’s an incredibly wealthy former presidential candidate whom voters never quite grew to love in 2008 and voted for begrudgingly in 2012. And now, with a real fighter firmly entrenched in the White House, the conservative movement doesn’t need Romney anymore.

Author: Jane Coaston

Read More