The GOP’s new, much narrower infrastructure counteroffer, explained.

Senate Republicans have unveiled their $568 billion infrastructure counterproposal. While it sets a substantial amount of money toward fixing roads and bridges, it’s about a quarter of the size of the Biden administration’s proposed infrastructure package.

There’s a wide gap between the price tag on the GOP plan and the $2.25 trillion American Jobs Plan President Joe Biden laid out. Not only is the cost much smaller; the Republican plan deals more narrowly with fixing America’s roads and bridges and other forms of transportation infrastructure, while Biden’s does that and more, doubling as a sweeping climate plan and a substantial investment to make long-term care more affordable.

Republicans argue that their infrastructure plan is “robust.” Though it’s a fraction of Biden’s proposal, the Republican plan is actually larger than the last $305 billion bipartisan infrastructure bill Congress passed in 2015 that was signed into law by President Barack Obama. But the difference between these numbers and Biden’s latest plan underscores just how much Democrats have raised the stakes in the last five years. To Biden, infrastructure isn’t just about roads and bridges; it’s the last best hope the US has to tackle climate change in a real and fundamental way.

The Biden administration held the first of a two-day international climate summit on Thursday, unveiling a new emissions target cut America’s greenhouse gas emissions 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. Biden’s campaign pledge on emissions was getting the US to net-zero emissions by 2050, and getting the American economy to run on 100 percent clean and renewable energy by 2035. To do that, Biden intends to move the US economy aggressively towards clean energy — which will take significant federal investment.

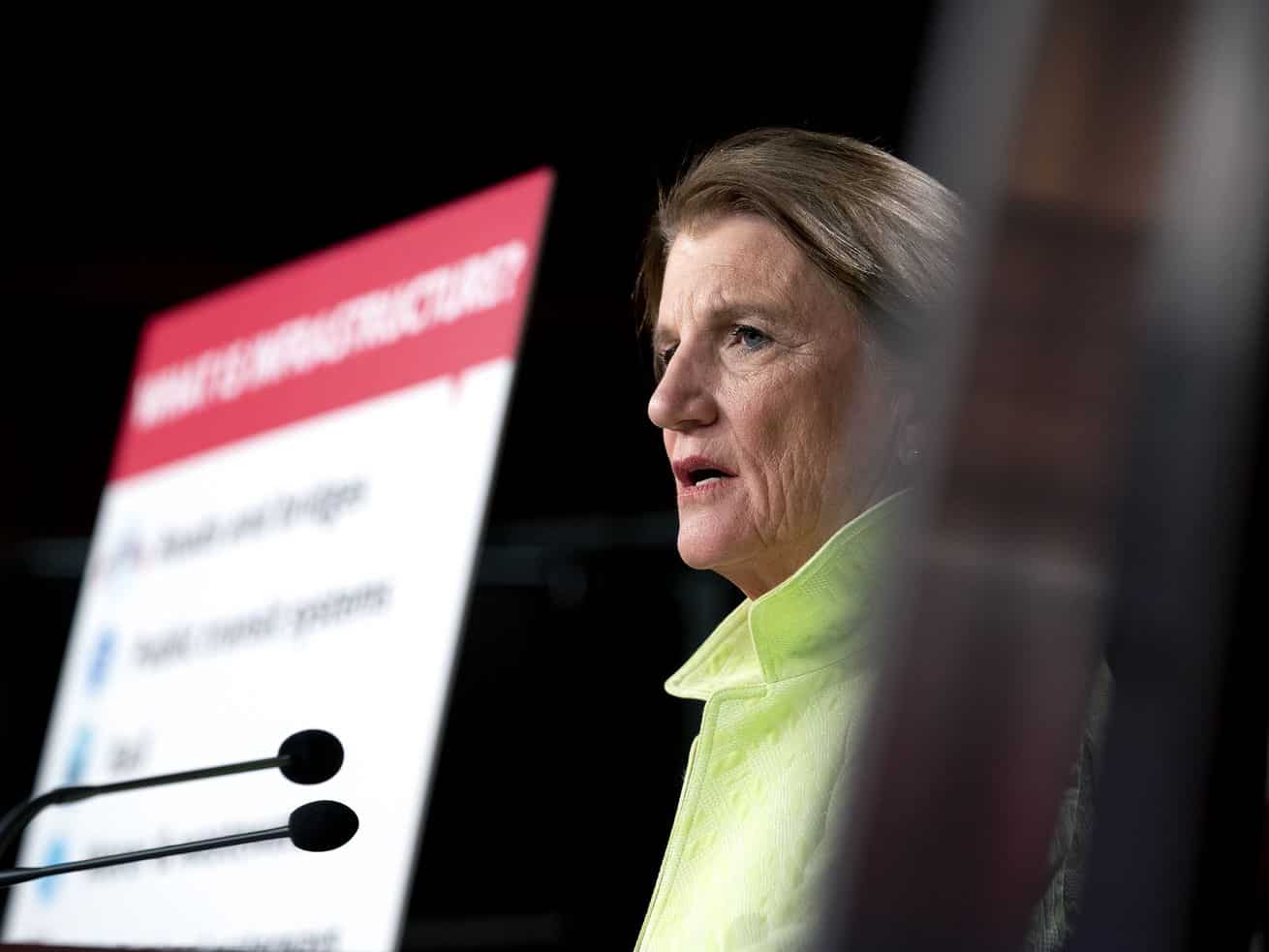

“We expect that when we get to the negotiating phase, climate will be a part of the discussion,” Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV), the lead Republican on the bill and ranking member of the Senate Environment and Public Works Committee told reporters on Thursday. There is some funding for electric vehicle infrastructure in the Republican plan, but it pales in comparison to Biden’s. Biden’s plan also contains a clean electricity standard, which many clean energy advocates see as a key way to cut US greenhouse gas emissions dramatically.

Even though Capito and Republicans said they see their plan as a starting point in negotiations with the White House, it remains to be seen if the Biden administration thinks the gap is too wide, especially given the different approaches to the climate crisis. White House press secretary Jen Psaki called the Republican proposal a “good faith effort,” and said the president is willing to have the discussion in the coming weeks. Psaki also said the White House sees more time to negotiate with Republicans than there was on Biden’s $1.9 trillion Covid relief package.

“There are a lot of details to be discussed, but we do see them differently,” Psaki said. “The American Rescue Plan was an emergency package. We have a little bit more time here, and we’re very open to hearing a range of options, a range of mechanisms for moving it forward.”

What’s in the Republican proposal on infrastructure

The release of Biden’s American Jobs Plan prompted a lot of debate about what’s actually considered “infrastructure,” with Republicans arguing that it should be limited to investments in traditional resources like roads, bridges and public transit — which make up the bulk of their plan.

Broadly, Biden’s plan includes $621 billion for transportation infrastructure, including $115 billion for roads and bridges, $85 billion for public transit, $80 billion for passenger freight and rail and $174 billion for electric vehicle infrastructure. But it also includes $650 billion for home infrastructure like replacing lead pipes and installing broadband across the country. It also includes $400 billion to bolster long-term care, making the cost of caring for the elderly and disabled more affordable, and increasing pay for home health aides who look after them.

The Republican plan is much more narrowly focused. It includes these categories:

- Roads and bridges, $299 billion

- Public transit systems, $61 billion

- Safety, $13 billion

- Drinking water and wastewater infrastructure, $35 billion

- Inland waterways and ports, $17 billion

- Airports, $44 billion

- Broadband infrastructure, $65 billion

- Water storage, $14 billion

The other major difference between Biden’s proposal and the Senate Republican one is how it would be paid for. Biden has proposed raising the corporate tax rate to 28 percent to pay for his plan; Republicans have rejected raising taxes and are upset that Democrats are seeking to undo portions of their 2017 tax cut plan.

Here, Republicans are instead offering up a mix of electric vehicle user fees and repurposed unused federal spending, although there are few concrete pay-for details in their initial plan. They call for “all users of certain types of infrastructure (ex.: electric vehicles)” to contribute to new revenue. Republicans also want to repurpose unused federal funding from the Covid-19 relief bill and extend the cap on the state and local tax deduction that some Democrats want repealed.

What happens if Republicans and Democrats can’t agree on infrastructure

Democrats’ approach to Covid-19 relief offers a glimpse of what could happen if the two parties don’t reach an agreement on infrastructure. Thanks to a procedural maneuver by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, Democrats now have two more opportunities to use budget reconciliation to pass their key priorities with just 51 votes in the narrowly divided Senate, and they just might use one of them on infrastructure.

“If [Republicans] don’t see the big, bold need for change in infrastructure and climate that the nation sees and wants and that we see and want, we will have to move forward without them,” Schumer said last week in a CNN interview. “But our first preference, let’s see if they can work in a bipartisan way.”

Some Republicans have signaled that there’s room for common ground, as evidenced by the proposal they put forth on Thursday: Capito and Carper, for instance, have already collaborated on water infrastructure legislation intended to invest in resources that would improve access to clean drinking water. And Sens. Chris Coons (D-DE) and John Cornyn (R-TX) have previously floated the idea of approving a bipartisan $800 billion infrastructure measure, and considering the more contentious tenets separately.

Whether a bipartisan agreement is actually possible, though, remains to be seen: Key Democratic priorities, including a $400 billion investment in boosting long-term care access, have been dinged by Republicans for being extraneous. And Republicans’ opening $568 billion bid — much like in the case of Covid-19 aid — is but a fraction of the more than $2 trillion plan that Biden has proposed.

Depending on how much both parties are willing to compromise, it’s very possible that Democrats end up moving unilaterally, again.

“Until the Republicans realize the needs are far, far greater from what they’re proposing, I don’t know that we’re going to get much further. I hope so … but we’re not going to wait forever,” Sen. Mazie Hirono (D-HI) told Politico.

Exactly what Democrats would be able to do under reconciliation is still somewhat unclear at the moment: Since such bills must focus on taxing and spending, all provisions are subject to review of the parliamentarian, Elizabeth MacDonough, who can determine whether certain tenets need to be stripped out. Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR), chair of the House’s Transportation Committee, is among those who’s wondered whether programs including surface transportation and wastewater authorizations would qualify.

“You cannot create a new program in reconciliation. There are myriad things you can’t do in reconciliation,” he told Reuters’s Susan Cornwell in mid-April. “The parliamentarian has a séance with a senator that has been dead for 11 years and created a rule 37 years ago. It’s arbitrary, capricious and stupid.”

Confronting that question will be Democrats’ next challenge if they decide, once more, to go it alone.

Author: Ella Nilsen

Read More