His death highlights how officers are rarely charged or convicted in police shootings.

Two Sacramento police officers who shot and killed an unarmed black man as he stood in his grandmother’s backyard last year will not be charged in his death, prosecutors announced Saturday, making this the latest high-profile police shooting where officers are not held criminally accountable for using deadly force.

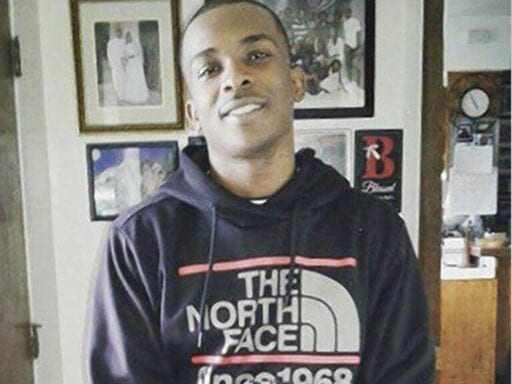

Stephon Clark, 22, was shot dead last March after police responded to a 911 call warning that a man was breaking into cars in the neighborhood. Sacramento police officers, later identified as Terrence Mercadal and Jared Robinet, chased after Clark into his grandmother’s backyard and fired some 20 bullets at him, believing Clark had a gun in his hand. Instead, it was actually an iPhone.

According to the official coroner’s report, Clark was shot seven times by police. However an independent autopsy, ordered by Clark’s family, found eight bullet wounds — six of which were fired into his back.

The investigation into Clark’s death was drawn out for nearly a year, but ultimately on Saturday, Sacramento County District Attorney Anne Marie Schubert said the evidence justified the officers’s use of deadly force. Extremely graphic body camera footage shows that one officer issued verbal warnings before they opened fire: “Show me your hands! Gun! Show me your hands! Gun, gun, gun!” Helicopter footage “shows that Mr. Clark was in fact advancing on the officers,” Schubert said, without specifying how long that was before they actually opened fire.

“There is no question that the death of Stephon Clark is a tragedy, not just for his family but for this community,” Schubert said at a press conference Saturday, later adding that “we must recognize that [police officers] are often forced to make split-second decisions.”

Clark’s family filed a $20 million wrongful death lawsuit against Sacramento in January, alleging in part that he was a victim of racial profiling. They complain that in the aftermath of the shooting, authorities used character assassination tactics to discredit Clark — police released text messages and phone records showing he was despondent after a domestic violence dispute with the mother of his two children. Authorities suggested he was suicidal and he searched for deadly combinations of drugs and alcohol.

“They executed my son,” the victim’s mother, SeQuette Clark, said at an emotional press conference on Saturday. “They executed him in my mom’s backyard. And it is not right. It is not right. . . . We’re not going to accept that. We’ve been sitting for a year patiently allowing [Schubert] an opportunity to do right, and she has failed us.”

Four years since the rise of Black Lives Matter, police convictions remain elusive

Clark’s death sparked waves of protests throughout Sacramento last year, as activists demanded greater accountability on police use of force. For many, his case represented the continued scourge of unarmed black men who are shot dead by police, years after the Black Lives Matter Movement first inspired a national reckoning over excessive police force and violence.

Clark was just the latest unarmed black man to be shot dead by police in Sacramento alone. His shooting prompted Sacramento to enact new police reforms, and the city adopted a new policy discouraging foot pursuits. The changes were created to remind officers “what they’re supposed to think about, what they’re supposed to weigh anytime they get into a situation when they’re chasing after a suspect,” Sacramento Police Chief Daniel Hahn said last year.

Activists, however, say that’s not enough, and that Mercadal and Robinet should have been prosecuted. But it’s still fairly uncommon of officers to be held criminally accountable for using deadly force.

As Vox’s German Lopez explained in Clark’s case last year, law enforcement has an exceptional amount of leeway in police-involved shootings. And even if cops are charged, statistics show they are rarely convicted:

Police are very rarely prosecuted for shootings — and not just because the law allows them wide latitude to use force on the job. Sometimes the investigations fall onto the same police department the officer is from, which creates major conflicts of interest. Other times the only available evidence comes from eyewitnesses, who may not be as trustworthy in the public eye as a police officer.

Clark’s family and the activist community supporting them wanted desperately for their case to be the exception to the trend. Instead, they found out Saturday that more than four years after Michael Brown’s death in Ferguson inspired a nationwide movement on police accountability, the prospect of officers being charged — let alone convicted — for the shooting deaths of unarmed black men remains exceptionally rare.

Author: Amanda Sakuma

Read More