A growing body of research finds the antimalarial doesn’t help hospitalized coronavirus patients.

Does President Trump’s favored coronavirus treatment, the antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, make you more likely to die of Covid-19? That was the finding in a recent study published in the medical journal The Lancet. The study looked at more than 96,000 coronavirus patients across the world and found that, after controlling for age, sex, and how sick the patients were, patients receiving hydroxychloroquine or a variant were about twice as likely to die as those who did not.

The result quickly made headlines in top papers, may have spurred the World Health Organization to discontinue the use of hydroxychloroquine in an ongoing drug trial, and may change the way tens of thousands of coronavirus patients worldwide are treated over the next few months. Former leading Food and Drug Administration official Peter Lurie called the study “another nail in the coffin for hydroxychloroquine — this time from the largest study ever.”

It wasn’t the first study to find that hydroxychloroquine doesn’t seem to improve outcomes for patients. But The Lancet study was by the far the most aggressive in its conclusions, finding that hydroxychloroquine wasn’t just ineffective, but outright dangerous.

However, as other researchers have looked more closely, they have discovered vexing problems with the study. For instance, the reported effect of hydroxychloroquine on deaths is significantly larger than the effect found in other studies. They also found that the study includes more patients from Africa than there were patients hospitalized anywhere in Africa at the time. And because the authors of the study have said their data sharing agreements do not allow them to share their data, other researchers have been forced to pore over the study trying to explain such anomalies.

To be clear, none of the confusing data problems that researchers are puzzling over mean that the study is necessarily wrong. They’re not proof of fraud or malpractice, either. When combining data from all around the world for a massive analysis like this one, some reporting errors are pretty likely.

But the resulting controversy around the study is less a vindication of hydroxychloroquine — the weight of the evidence still points to it not being effective against the virus — and more a reminder that, urgent as this crisis is, people should try not to treat any one study as definitive, and should allow time for flaws and concerns to be discovered (which will mostly happen post-publication).

Scientists are doing amazing things in response to this crisis. But the new, fast scientific process (and even the old, slow scientific process) can produce errors — sometimes significant ones — to make it through peer review. When we’re drinking from the firehose of attention-grabbing coronavirus research, we should make sure to stay skeptical, ask questions, and remember how much we still don’t know.

The Lancet’s hydroxychloroquine study, explained

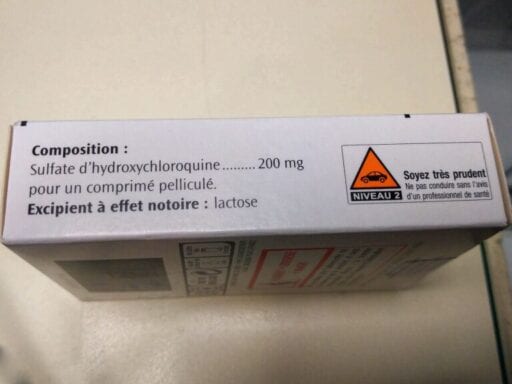

Hydroxychloroquine is an anti-malarial medication. But since early in the coronavirus pandemic, there’s been interest in using it as a coronavirus treatment, for many reasons.

First, it shows significant antiviral action in petri dishes. (Being bad for viruses in a petri dish doesn’t necessarily predict it’ll be effective against them in the human body, but it’s a decent starting point.) Second, it’s cheap, widely available, and generally considered safe; that made it seem “worth trying” even before there was much data about how well it would work.

Doctors were trying the drug with sick patients in February and March. It was one of many potentially promising treatments but early results were mixed. Nonetheless, in late March, comments by Trump spurred a wave of intense interest in hydroxychloroquine, briefly leading to mass off-label prescribing and shortages for patients who needed it for other conditions.

Since then, though, some data has started coming in — and it mostly hasn’t looked that promising. Various randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have largely failed to detect benefits of hydroxychloroquine or its variants as a treatment protocol. A few have found a small increase in deaths. While hydroxychloroquine is generally considered a safe medication with well-known and fairly minimal side effects, that’s when it is prescribed to healthy people; it might stress the systems of people who are already sick.

The golden standard for a study of disease treatment is a RCT, where patients are assigned at random to get a treatment or a placebo. The study published in The Lancet was not a RCT. Instead, it looked at 96,000 patients, what they were treated with, and what their outcomes were. The authors — Mandeep Mehra, Sapan Desai, Frank Ruschitzka, and Amit Patel — looked at data from “671 hospitals in six continents,” including 14,888 patients who received hydroxychloroquine or a variant.

Of course, it is entirely possible that hospitals mostly gave hydroxychloroquine to their sickest patients. Alternatively, they could’ve mostly given it to healthier patients, disproportionately prescribed it for young people, or for patients without a history of heart problems. Any tendency like that would mean that the study might find benefits or harms to hydroxychloroquine where none really existed.

The study attempts to fix this by controlling for differences between the treatment group and the control group in every confounding factor they could think of: “age, sex, race or ethnicity, body-mass index, underlying cardiovascular disease and its risk factors, diabetes, underlying lung disease, smoking, immunosuppressed condition, and baseline disease severity.”

Their finding? Once you control for everything, hydroxychloroquine looks deadly. The study finds mortality in the various hydroxychloroquine treatment groups between 16 percent and 24 percent, while mortality in the control groups was 9 percent — implying that treatment with hydroxychloroquine doubles the risk of death.

But there are some reasons to doubt that eye-popping number. First, it’s inconsistent with other studies, which have not been good for hydroxychloroquine but which have not detected negative effects anywhere near that scale. A large study in the New England Journal of Medicine, for example, found no effects of hydroxychloroquine on mortality (and used a more detailed method of controlling for disease severity than the one used in The Lancet study).

Second, the study authors don’t find a relationship between the dose given and the death rate (different hospitals have prescribed the drug at different doses). Research has found that in chloroquine overdose-related deaths, higher doses strongly predict the death rate. If the medication looks equally dangerous no matter how much of it is prescribed, that can be a sign that there’s some sort of statistical problem.

Third, there are some oddities in The Lancet study’s data. Medical researcher Anthony Etyang posted on pubpeer, a site where scientists review each other’s published papers, “The article reports 4,402 patients from Africa as at [sic] 14th April 2020, which looks rather high, given that by that date, according to the Africa CDC, there were a total of 15,738 cases reported among the 52 countries in Africa. The majority of cases are asymptomatic and not hospitalized, so the pool of patients available to join this study would have been even smaller than the 15k.”

“There is sometimes a delay before public health agency reporting catches up to data at the hospital level,” Sapan Desai, one of the co-authors of the paper, told me in response to this concern. “Public health data could have been under-reported early on during the pandemic, thus leading to the appearance that we are over-reporting numbers when in actuality we are capturing the true total number of Covid-19 infections at the hospital level.”

The data from Australia has a similar problem — the study reports more deaths in hospitals than the Australian government does. The researchers have since clarified that a hospital in Asia was mistakenly classified as one in Australia, and are correcting the data, though they say it won’t change their conclusions. But the error does raise a flag — “If they got this wrong, what else could be wrong?” Melbourne epidemiologist Allen Chang asked.

Furthermore, the listed average daily doses for the drug are higher than generally recommended anywhere in the world.

The study “suffers from enough statistical bias to mask a beneficial effect of the drug,” public health researcher Zoe McLaren argued. In other words, omitting just a couple of confounding variables would be enough to change the results entirely.

There are reasonable explanations for the minor oddities in the study. It’s entirely possible that hospitals in Africa saw more coronavirus patients than national governments reported, because of complications or delays in reporting. It’s possible the Australian government’s numbers are a little off. It’s possible hospitals were routinely giving higher doses than the guidelines recommended. But since none of the data is available, the significance of questions like these is hard to evaluate, and researchers are stuck asking one another questions on the internet.

It doesn’t help that The Lancet, in particular, has erred badly in the past (for example, by publishing a fraudulent paper claiming that vaccines cause autism and taking more than 10 years to retract it) or that the rushed publication process left some glaring, easy-to-notice errors in the data (like the Australian deaths not adding up).

For their part, the authors stand by their work, arguing that their results are largely in line with other research. “With these findings, we join agencies including the FDA, as well as several other observational studies reported in the NEJM, JAMA, and the BMJ, each of which have pointed to either no benefit of drug regimens using hydroxychloroquine or chloroquine or even a signal of potential harm in a hospitalized population,” Desai told me.

Science is hard — and speeding it up lays bare many of the challenges

All of the challenges associated with this study are actually quite normal. Lots of research has confusing data that isn’t public, and lots of research makes it past peer review even as other specialists in the field have doubts about it. Richard Horton, editor of The Lancet, said in 2015, “Much of the scientific literature, perhaps half, may simply be untrue.”

Much discussion of mistakes and misinformation in the age of the coronavirus has focused on preprints, studies published online before peer review. But learning what research is right is much more complicated than just waiting for peer review.

Peer-reviewed research is also “provisional knowledge — maybe true, maybe not,” Columbia University statistician and research watchdog Andrew Gelman argued in an article about the hydroxychloroquine Lancet study, playing off a quote from a New York Times op-ed. “As we’ve learned in recent years, lots of peer-reviewed research is really bad. Not just wrong, as in, hey, the data looked good but it was just one of those things, but wrong, as in, we could’ve or should’ve realized the problems with this paper before anyone even tried to replicate it.”

It takes a lot more than just the formal peer-review process to notice and correct problems in papers. It requires a large, engaged scientific community that keeps asking questions before and after formal publication, and it takes engaged original authors who take those criticisms to heart and work to explain and address concerns.

Those things are all the more true during the pandemic, when studies are discussed around the world — and in the headlines — the instant they’re published, and often treated as more definitive than they should be. Only a week after this study was published, with new concerns about it coming out every day, other research has already been canceled since its release partially on the basis of its strong claims. We should keep in mind that many parts of the scientific process can and should be hurried, but that it takes time and discussion to arrive at the truth. While that’s underway, all our knowledge is provisional.

And figuring out the truth takes data sharing. When data is public, concerns can be quickly addressed and corrected. “With proprietary data sets that I couldn’t just go look at, I wouldn’t have been able to look and see that this was clearly wrong,” one researcher told me after discovering a glaring error in behavioral scientist Paul Dolan’s book about human happiness last year.

The higher the stakes, the more important it is that researchers step up and take an active role in uncovering any flaws in their research. They should engage with criticisms and concerns from other researchers. They should engage with journalists to make sure we’re explaining their research correctly. Often, in these wild times, we have to move ahead with the best information we have, even if it’s suboptimal. But being honest about what we know and what we don’t will serve us well.

Support Vox’s explanatory journalism

Every day at Vox, we aim to answer your most important questions and provide you, and our audience around the world, with information that has the power to save lives. Our mission has never been more vital than it is in this moment: to empower you through understanding. Vox’s work is reaching more people than ever, but our distinctive brand of explanatory journalism takes resources — particularly during a pandemic and an economic downturn. Your financial contribution will not constitute a donation, but it will enable our staff to continue to offer free articles, videos, and podcasts at the quality and volume that this moment requires. Please consider making a contribution to Vox today.

Author: Kelsey Piper

Read More