The city I loved was shut down this year. I found comfort in the beloved TV show’s idealized version of it.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21899595/VOX_The_Highlight_Box_Logo_Horizontal.png)

Episode 4116 of Sesame Street, which first aired in 2006 but which premiered in our apartment in the spring of 2020, starts with Elmo playing school.

Elmo has paper and crayons but needs a teacher, so he recruits Alan, the human who runs the convenience store on Sesame Street. It’s stressful for Alan not only because he has never taught school before, but also because he still has to deal with the store. Just as he’s starting to get used to his new role in Elmo’s life, a Muppet bus driver delivers at least a dozen human students to the convenience store, backpacks on, ready to learn.

“I hear you’re up for Teacher of the Year,” the bus driver barks in a New York accent as Alan blinks in confusion and defeat. “Congratulations!”

I watched this episode in fragments, like so many things I did this spring, this year, this season of my life. We started watching Sesame Street last November because our baby, then about 18 months old, had been diagnosed with asthma. He needed twice-daily nebulizer treatments, which required him to sit still for a seemingly endless 15 minutes with a mask over his face as a machine blew steroid steam at him. The baby did not want to sit still under any circumstances, least of all these. The only thing that worked was TV, and one of the least unpleasant options, from my perspective, was Sesame Street.

For a long time, the solution worked for both of us. He liked Elmo and repetition; I liked the Yip-Yips and the gentle humor I remembered from my own youth. But in March, when we took the baby out of day care, sheltered in our apartment, and started watching his breathing (and our own) obsessively for signs of Covid-19, Sesame Street stopped feeling comforting. It started feeling bizarre.

Episode 4116, for example, featured two activities — attending school and going out for a meal — that had just been banned in the real New York City. Every episode gave me whiplash: A kid bounds happily out of the subway, friends laugh together on the playground, a gregarious orange Muppet visits iconic Manhattan sites and chooses people gathered there for a casual, mask-free interview. Especially in March, with the city still in strict lockdown, Sesame Street felt like a joyful celebration of every formerly fun, or at least normal, New York activity that had now become suspect, dangerous, even fatal.

Of course, this was true of all media this year, when it became strange to watch people hug on TV like it was nothing, or to see a train station framed as anything other than a superspreader event waiting to happen.

But Sesame Street was especially wrenching. Launched in 1969, the show became popular with kids (and adults) across the country but has always been rooted very specifically in New York City. Many of its storylines revolve around the kind of neighborhood relationships that can be fostered by city living, like the ones between Alan and the Muppets and humans who live near his convenience store. These are idealized on the show, of course, but still likely familiar to a lot of New Yorkers. A few years back, for instance, the manager of our local convenience store mused to me that at his job, he can track his neighbors’ whole lives — he sees mothers come in pregnant, then watches their babies grow up.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22161182/GettyImages_1171146068.jpg) Bill Pierce/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images

Bill Pierce/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22161195/GettyImages_1014190254.jpg) Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty ImagesThe show’s New York connection is very much by design. Its setting is a fictional block based on real ones — the show’s original set designer scouted Harlem, the Upper West Side, and the Bronx for inspiration, according to Smithsonian magazine, and populated its world with brownstones and garbage cans recognizable to any New Yorker. Sonia Manzano, the actor who played the long-running character of Maria, has said that she recognized her own Bronx neighborhood when she first saw the show in college: “Hey,” she said, “that’s my street!”

One of the joys of the city — one that Sesame Street documents so well and so sweetly — is the way it brings people together. But when togetherness became dangerous, this joy turned to grief and fright, and Sesame Street felt almost like a memorial, a relic of a New York that was never coming back.

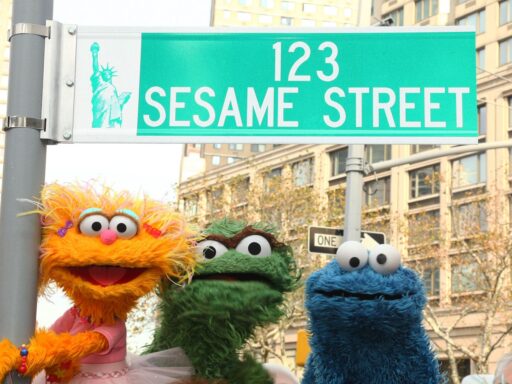

Sesame Street, then and now, is all about a tight-knit New York community. The original set included Luis and Maria’s Fix-It Shop, the convenience store, and 123 Sesame Street, the apartment building occupied by Bert and Ernie and their various human neighbors. Crucially, it also included the front stoop of 123, where the Muppets and people all hung out. “Our set had to be an inner-city street, and more particularly it had to be a brownstone so the cast and kids could ‘stoop’ in the age-old New York tradition,” producer Jon Stone told Michael Davis, author of the Sesame Street history Street Gang.

The set has changed a bit over the years; in 2015, for example, scenic designer David Gallo added a community garden. But the stoop, and its spirit, remain. The show is all about neighbors coming together — helping, teaching, amusing, and exasperating each other.

In the real New York, by mid-March, the kind of neighborhood life celebrated on Sesame Street felt like a unique danger, rather than a distinct pleasure, of city living. The corner stores and apartment buildings were outbreaks waiting to happen. Laundromats, once a mundane weekly gathering place, had become a locus of fear for many New Yorkers; those who could afford it were buying in-home washing machines, while others did laundry in their bathtubs. Parties were banned. Even the gates to playgrounds were padlocked shut.

As March turned to April, I started taking walks in the early morning. When someone else approached, one of us would usually cross the street to avoid the other. No distance seemed safe. Once, the baby coughed during a walk in the park; a jogger, hundreds of feet away, turned around and ran in the opposite direction.

And no wonder we feared each other. At the first peak of the epidemic, in mid-April, more than 800 New Yorkers were lost to the virus in a single day. The hospitals were overwhelmed. Refrigerated trucks drove in to hold the dead. Sirens were never-ending. At night, I could hear coughing all up and down my street.

Politicians and pundits talked about New York as though its residents and their lives were the problem. The apartment building, the laundromat, the subway, the corner store, the stoop — it was not the virus, but our perverse insistence on living in close quarters with one another, that was killing us. Even Gov. Andrew Cuomo (D) tweeted in March that “there is a density level in NYC that is destructive,” calling on the city to develop an immediate plan to reduce it.

It was a strange thing to ask of a city in crisis, but wealthier residents did their part, decamping for country houses and suburbs and launching a thousand trend pieces about the end of cities.

Those were quickly met by critics pointing out that it wasn’t cities themselves but inequality within cities that was causing much of the death and devastation during the pandemic. I never really believed New York was “over” (for starters, most people couldn’t afford to simply take off for the suburbs even if they wanted to), but it was still hard to imagine a return to the kind of blithe hanging out depicted on Sesame Street. And even the silliest storylines felt to me like reminders of everything we were missing — Muppet fairy Abby helps her friend get ready for a party (parties?!); Elmo and his friends make up a song about the number 3 (singing is one of the most dangerous things you can do!); kids discuss what they learn in preschool (if only).

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22174732/GettyImages_469586834.jpg) Dana Edelson/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty Images

Dana Edelson/NBCU Photo Bank/NBCUniversal via Getty ImagesOf course, in the scheme of this dark year, what my family had lost barely registers. My husband and I could work from home, where we took care of our son in shifts, I the morning and he the afternoon. Like so many in New York this spring, we got sick, but then we got better. We’ll probably never know for sure what we had. And the baby’s medicine worked, or his youth did — despite his asthma, he played his way through our March illness, the least affected of any of us. This winter, as the virus surges past its spring peaks in much of the country, we’re sheltering in place, watching the numbers anxiously but aware that, for the time being, New York is actually one of the safer places to be.

Sometime around early May, our son began to get tired of Sesame Street. He’d twist in our laps and yell “Skip!” when Elmo had barely spoken a word. We switched to Daniel Tiger, then to a show called The Bumble Nums about little aliens who are great at cooking. But as we moved further from Sesame Street in our daily routines, real life started to look more like Sesame Street again.

First, I noticed people saying hello to the baby. A constant occurrence before the pandemic, it had all but stopped in March and April, as his neighbors clearly regarded him (perhaps rightly) as a vector of disease. But in the park one May morning, a man asked me, from behind his mask, how old my son was.

“Almost 2,” I said from behind mine. Not a baby anymore.

Businesses began to reopen — the taco place, the coffee shop where I’d sat with copy edits of my book in early March, wiping the table before setting down the manuscript. We started going back to the corner store, buying chocolate, bleach wipes, and beer. The manager and his family were healthy, he said, though he was stretched thin. Like Alan, he’d suddenly found himself a de facto teacher, helping his three kids with their online school at night while running the store during the day.

The truth is that neighborhood life never actually ended in New York City, even if its most privileged residents sheltered from it for a time. Thousands of workers rode (and ran) the subways every day, even at the height of the pandemic. Thousands more still took their children to day care — facilities set up by the city and the YMCA to care for the kids of essential workers operated for months without an outbreak.

Meanwhile, the kind of stoop socializing celebrated by Sesame Street rebounded quickly as it became clear that outdoor interactions were safer, from a Covid-19 perspective, than indoor gatherings. “Stoop drinks” and block parties became a summertime escape from the monotony of quarantine (though, as always, Black and Latinx New Yorkers who got together outdoors were vulnerable to targeting by the police).

And all around the city, all of this year, New Yorkers have been coming together to help each other. You see it in small things — our rates of mask use remain some of the highest in the country — and in bigger ones, too. When the pandemic confined many older and immunocompromised people to their homes, mutual aid organizations sprang up to get them groceries. When millions around the country rose up to protest police violence and the killings of Black Americans, New Yorkers marched with their neighbors, handing out masks and hand sanitizer all the while. When the mayor imposed a curfew, New York community groups stepped in to give bail money, legal help, and medical care to protesters arrested or hurt by police.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22162981/GettyImages_1243823673.jpg) Ira L. Black/Corbis/Getty Images

Ira L. Black/Corbis/Getty ImagesThe problems of New York run deep — the lack of affordable housing, the segregated schools, the underfunded public transit system that’s lost even more money during the pandemic — and they’ll probably get worse before they get better. And the working-class Black and Latinx communities that Sesame Street intentionally set out to celebrate, in a way that was groundbreaking for network TV at the time, have been especially hard-hit by Covid-19 and are especially underserved by the economic relief handed down by the federal government so far.

But the communal spirit that Sesame Street champions hasn’t disappeared from the city of its birth, even if it often seems absent from the halls of power. As the country lurches into a long winter with relief from the virus still feeling far away, I’m drawing from the show a certain fragile hope.

I didn’t stop watching Sesame Street when my son got sick of it. Instead, I went back to the archives.

I remembered that even though most of the episodes I watched in the spring were sunny and fun, Sesame Street is actually famous for something all too relevant in America right now: talking about death.

One of the show’s most iconic episodes — indeed, one of the best-known episodes of children’s TV ever — is Episode 1839, which deals with the death of the beloved Mr. Hooper, the original owner of the convenience store (the same one Alan later managed and had to turn into a school). Will Lee, the actor who played Mr. Hooper, died in 1982, and instead of ignoring his departure, the creators of Sesame Street decided to address it by having the characters explain death to Big Bird, compassionately, but accurately.

The segment is deeply sad. At first, Big Bird doesn’t understand and keeps asking why Mr. Hooper isn’t coming back. Then he wants to know, “Who’s going to take care of the store, and who’s going to make my birdseed milkshakes and tell me stories?” One of Big Bird’s neighbors, David, reassures him: “I’m going to take care of the store,” he says. “Mr. Hooper, he left it to me. And I’ll make you your milkshakes, and we’ll all tell you stories, and we’ll make sure you’re okay.”

At the end of the episode, Big Bird’s neighbors all envelop him in a hug.

I can’t hug my neighbors now; when I meet friends in the park, we do pathetic “air hugs” around each other. Still, the episode feels like a template for how New Yorkers can care for each other in bad times as well as good.

Whether it’s Alan starting a school to help out Elmo or David stepping in to make milkshakes for Big Bird, Sesame Street is, at its core, about a true community whose members won’t let each other down, no matter what. New York isn’t that in 2020, and America certainly isn’t that. But amid the devastation of this year, I see glimmers of recognition that we’re going to need those kinds of communities if we’re going to come back from this. I see it in calls to support child care and other care workers, in the evolution and expansion of mutual aid groups (and others inspired by them), and in ideas for building a more equitable city. And while Sesame Street isn’t exactly a policy document, we could do a lot worse than to turn to it for guidance.

Someday, when my son is a little older, I hope we watch the show together again. I hope that we, as his parents, live up to the standards set by Alan, David, Mr. Hooper, and the rest. And I hope that when he sees the characters having fun together and helping one another, he finds something he recognizes in his own neighborhood.

Anna North is a senior reporter at Vox. Her novel Outlawed will be released in January 2021.

Author: Anna North

Read More