Five of the museum’s Dead Sea Scroll fragments have been declared fakes.

The Museum of the Bible announced Monday that at least five of its Dead Sea Scrolls — among the most valuable and historically significant items in its collection — are fakes.

According to a press release put out by the Washington, DC–based museum, a German testing company had concluded that the fragments on display showed “characteristics inconsistent with an ancient origin” and thus would no longer be on display at the museum.

“Though we had hoped the testing would render different results, this is an opportunity to educate the public on the importance of verifying the authenticity of rare biblical artifacts, the elaborate testing process undertaken and our commitment to transparency,” Jeffrey Kloha, chief curatorial officer for Museum of the Bible, said in a statement.

The five scrolls represent a major proportion of the museum’s 16-piece collection of Dead Sea Scrolls, acquired as part of the 40,000-piece Green family collection over the past decade. Doubts about their authenticity were first raised two years ago by scholars in the academic journal Brill. Since then, scholar Kipp Davis of Trinity Western University has argued that at least seven of the scrolls were fake, based on the language used in the fragments and other textual evidence.

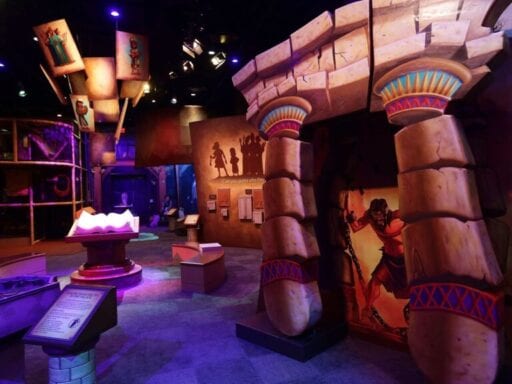

The announcement of the forgery comes after years of controversy and criticism over the museum’s approach to scholarship, which is heavily rooted in its evangelical Christian ethos. The 430,000-square-foot, $500 million museum, which opened in November 2017, is the brainchild of the Green family, the evangelical Christian owners and founders of the craft store chain Hobby Lobby. Last year, the museum sent five of the disputed fragments to a German laboratory for testing. The results, which were publicly released this week, cast serious doubt on the authenticity of all five.

The museum has consistently come under fire for its lack of rigor when it comes to acquiring and curating new items. In 2017, for example, Hobby Lobby was forced to return 3,800 ancient artifacts to Iraq after the Department of Justice concluded that the company had acquired them illegally and had them shipped to corporate headquarters without sufficiently documenting their provenance. (This process is important not just because it helps avoid acquiring forgeries, but because illegal antiquities deals, particularly in the Middle East, can provide a major source of funds for international terrorism.)

That’s why the discovery of the forgery isn’t just a piece of bad luck for the museum. Rather, it’s an inevitable reflection of a much wider issue: The Museum of the Bible’s evangelical founders have consistently allowed ideological concerns — and a particularly narrow vision of what the Bible is — to override standards of academic rigor.

The Museum of the Bible’s use of the Dead Sea Scrolls reflects a wider issue in biblical scholarship

The museum was originally conceived as a faith-based endeavor, designed to spread the message of the gospel; early plans for the museum involved pamphleteers passing out tracts urging visitors to accept Christ. In its current form, the Museum of the Bible purports to be a far more academic and religiously neutral institution. It boasts an interfaith board of advisers, many of whom are well-regarded religion scholars, and its director, David Trobisch, is a renowned New Testament researcher who formerly taught at Yale Divinity School.

Still, as religion scholars Joel Baden and Candida Moss write in their book Bible Nation, the museum and the Green family’s initiatives more broadly tend to prioritize the work of less-qualified, faith-based scholars over their more rigorous secular counterparts. For example, Baden and Moss write, the Green Scholars’ Initiative — which recruits academics to do curatorial work for the museum — commissioned an undergraduate classics class at Kent State University, with only a rudimentary knowledge of Ancient Greek, to transcribe and translate highly specific ancient documents.

The controversy over the Dead Sea Scrolls is about more than just the Green family’s academic rigor, or lack thereof. It’s also about the very particular way that many evangelical Christians see the Bible — a perspective that has made the evangelical market particularly susceptible to forgeries.

To understand that perspective, it’s important to understand what the Dead Sea Scrolls actually are. A group of documents and fragments discovered in the 1940s in a cave in Qumran in the West Bank, the Dead Sea Scrolls represent some of the most detailed information available about Jewish religious life and culture in the Second Temple period, the time around the life of Jesus Christ, including a number of different Jewish and early Christian sects.

Each Jewish sect had versions of Scripture that include texts outside the canon of what we know as the Bible today, as well as textual differences in versions of now-standard Bible books. This suggests an incredibly great diversity within Jewish religious experience and practice around the time of Jesus, as well as a great deal of overlap in imagery and theology between mystical Jewish sects that predate Christianity and Christianity itself.

As Baden explained to Vox, “The Dead Sea Scrolls totally blew apart our understanding of … the Bible. They revealed this enormous variety in the text, a canon that seemed to include a whole variety of previously unknown texts.” For example, the Dead Sea Scrolls showed that that the Book of Tobit, a religious text included in Catholic and Orthodox Scripture but not in Protestant or Jewish Scripture, was considered to be authoritative among these groups.

Baden said that the scrolls also demonstrate “an amazing fluidity in the history of the Bible.” This, Baden says, has long been the prevailing scholarly consensus about the documents’ significance.

But that’s not the narrative the people behind the Museum of the Bible want to further. Rather, Baden says, the museum’s signage and curatorial approach emphasize not the diversity represented in the Dead Sea Scrolls, but their similarities to the contemporary Christian Bible known today. Baden paraphrases the museum’s approach as “look how amazingly close this text is to our text … a sign of how consistent the transmission has been.”

The narrative favored by the museum, according to Baden, has “almost been entirely the opposite of what the Dead Sea Scrolls have always been about and what they mean for scholarship of our understanding the Bible.” Rather, he says, their “presentation absolutely fits into … a generic, a fundamentalist evangelical perspective that … the transmission of the Bible has been essentially perfect from the time of Jesus to the present.”

Within that paradigm, documents like the Dead Sea Scrolls take on a particular significance. Because they are old and historically significant, they are treated as “evidence” for a version of the Bible that is fundamentally unchanged throughout history. In turn, this drives up the demand, on the part of evangelicals, for material proof of this authenticity: documents that can be used to illustrate the fundamental consistency of the Bible throughout time.

This, in turn, Baden said, has created a thriving market among evangelicals for Dead Sea Scroll fragments — and thus a market rife for forgers, who recognize that religiously motivated, nonspecialist collectors might not have the same discerning eye as, say, academically trained researchers. “There’s … been fairly good evidence that forgers are targeting specifically evangelical buyers who are particularly eager to get their hands on a sort of tangible, material object that is so close to the earliest text of the Bible,” Baden said.

And when it came to the Museum of the Bible’s collection specifically, he said, “It’s not at all surprising to anybody in the academic world that they are forgeries.” Baden recalled attending a conference with one of his students, watching slides of the museum’s collection. Even his student, Baden said, could immediately tell that some of the fragments were forgeries, based on rudimentary discrepancies and errors that would have been familiar to any scholar.

The Museum of the Bible’s latest announcement, therefore, illustrates more than just the museum’s poor track record when it comes to correctly identifying and documenting the provenance of artifacts. It points to a wider lack of understanding of, or interest in, the very nature of academic inquiry about the Bible itself.

The museum’s designers have treated the Dead Sea Scrolls not as a valuable source of information about a very complex and diverse time in Jewish religious history, but as desirable “proof” of biblical inerrancy — a proof so desirable they were willing to risk acquiring forgeries to get it. They’ve failed to understand what, exactly, made the Dead Sea Scrolls so worth having in the first place.

Author: Tara Isabella Burton