LaBeouf wrote the film based on his own troubled childhood. It’s an exercise in extreme empathy, and a must-see.

People say art makes us more empathetic — and research seems to confirm this, to a degree — but I’ve always found the idea a little suspect; it’s not as if some of history’s greatest monsters weren’t also art lovers.

Nevertheless, a film can open your mind to others’ life experiences, if you’ll let it, and Honey Boy is no exception. But it also goes one step further: Honey Boy is, itself, an empathy generating exercise for its creator, in a way that seems both extraordinarily painful and courageous. It’s an intensely personal project for writer and star Shia LaBeouf, one that walks a thin tightrope but pays off beautifully.

LaBeouf wrote the screenplay for Honey Boy based on his own life, and it runs along two parallel threads. In one, a 22-year-old hotshot actor named Otis (Lucas Hedges) — LaBeouf’s stand-in — lands in rehab after his third drunken altercation with the police, and his therapist tells him he’s suffering from PTSD. As part of his recovery, he needs to recall his relationship with his father.

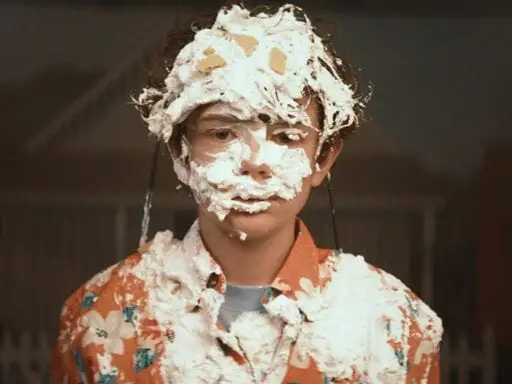

In the other thread, 12-year-old Otis (Noah Jupe) is a successful child actor with a steady income, some of which is used to pay his father James (LaBeouf, in a potbelly and balding mullet, playing his own father), who works as his chaperone, a requirement on set for child actors. James is a felon and an addict who’s been sober for four years, and a volatile and sometimes abusive parent, though he also clearly cares for and about his son. James and Otis live in a shabby motel room with two beds and spend their time together running lines, juggling balled-up socks, and listening to James tell bad jokes and stories of his glory days. Otis is growing toward manhood, but he’s still very much a little boy — still too innocent to do much more than dabble in the behavior that will eventually land him in rehab.

Honey Boy has the kind of premise that could very rapidly eat its own tail or become unconscionably sentimental. In fact, if the film was strictly fictional, it probably wouldn’t work at all, because it would feel strenuously contrived in order to garner sympathy. But all of it is based in fact, starting from LaBeouf’s successful career as a child actor, during which he played lead roles on the 2000-2003 ABC show Even Stevens and in the 2003 movie Holes. His screenplay was written mostly while he was in rehab following a 2017 arrest, much like we see in the film. And in the hands of director Alma Har’el (whose previous directorial work has largely been in documentary), is far too knowing and lived-in to fall into the sentimentality trap.

And while all three lead performances are standout, LaBeouf’s performance is almost breathtaking, if you pause for a moment to think about what’s happening. Empathy is finding a way to walk in someone else’s shoes, to get inside their head, to understand what makes them tick; in playing James, LaBeouf is literally embodying the definition of the word. James’s mannerisms and jokes and speech ticks and violent outbursts feel authentic, anchored in memory and in the kinds of close observations that children make of their own parents. Imagine trying to understand a person who caused you so much pain that you developed PTSD by playing them with warmth, humor, and depth on screen. That kind of lacerating love is difficult to fathom.

Honey Boy reminds us what it’s like to grow up in public — and helps illuminate LaBeouf’s career, too

Honey Boy doesn’t make excuses for James; it’s not an apology for a man who caused harm. Rather, it’s a dive into memory that feels typical for LaBeouf: The actor has been the object of both ridicule and wonder for his antics over the years, which have included run-ins with the law and baffling performance art projects along with performances in a wide variety of films, from Transformers to works by auteurs like Andrea Arnold and Lars Von Trier.

In fact, watching Honey Boy, I found myself thinking about his 2015 art project, which took place at New York’s Angelika movie theater, two years before the rehab stint that spawned this movie. With little warning, LaBeouf — whom the New York Times described as being “known for his erratic behavior” — announced that he’d be watching all 29 of his movies back-to-back in reverse chronological order, and invited the public to join him in person or via a livestream focused on him. It took three days, and he called the project “All My Movies.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19175443/458860222.jpg.jpg)

The internet erupted with jokes, but people went and watched. And reports began to emerge that watching LaBeouf watch himself was surprisingly moving. He laughed. He cried. He started earning praise for his “performance” from critics. Later, he said in an interview that at first the project seemed ironic and silly, but eventually felt like it “wound up in this very cool, sincere place.”

And now, having seen Honey Boy, that reaction makes a lot of sense to me. Watching your younger self on screen isn’t just watching a record of performance; it’s being reminded of what you were going through as you were filming. And LaBeouf’s complicated relationship with his father, and his subsequent substance abuse and brushes with the law, were inextricably linked to those earlier parts of his career. Of course he was crying.

The first scene in Honey Boy rapidly and skillfully illustrates how growing up on a movie set, living your life in public, means you start to meld fiction and reality; with Honey Boy, LaBeouf plays that mushy sense of reality to his full advantage. Watching the film, I felt like I learned something about the radical nature of really trying to understand someone else’s life — and how harrowing and beautiful the results can be.

Honey Boy premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in January and played at the Toronto International Film Festival in September. It opens in theaters on November 8.

Author: Alissa Wilkinson

Read More