One lesson: “Do not take Black women for granted.”

“Finally!”

That’s Georgia nonprofit leader Deborah Scott’s reaction to this year’s election, where massive Democratic turnout looks to have flipped the state blue for the first time since 1992. “We’ve been trying to get here for the last 15 years,” the executive director of Georgia Stand-Up, a group that works on civic engagement and other issues, told Vox. “I’m so happy that we’re at this moment.”

It’s a moment many Democrats are celebrating — and analyzing — even as the state heads for a recount. And around the country, millions of Americans are paying attention — finally — to organizers in Georgia, many of them Black women, who have spent years trying to get people to the polls.

Many say it’s been an uphill battle against restrictions designed to keep Black voters away. That battle got nationwide attention in 2018 after Democrat Stacey Abrams narrowly lost the gubernatorial election to Republican Brian Kemp, the secretary of state who had presided over purges that eliminated more than a million people from the state’s voting rolls between 2012 and 2016.

Abrams went on to found a voting rights group called Fair Fight, whose nonprofit arm sued the state in November 2018, arguing that its election policies disproportionately impacted — and even disenfranchised — Black and other voters of color in the state, as P.R. Lockhart reported for Vox at the time.

That suit is still ongoing, and with Fair Fight also working on voter registration and other grassroots activism in Georgia, Abrams has been getting a lot of credit for the 2020 results. But organizers (including Abrams herself) say it has been a team effort among larger organizations like Fair Fight and Black Voters Matter and local groups knocking on doors, texting voters, and providing rides to the polls. “The biggest factor was the network,” Amber Bell, program director at the Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education, told Vox.

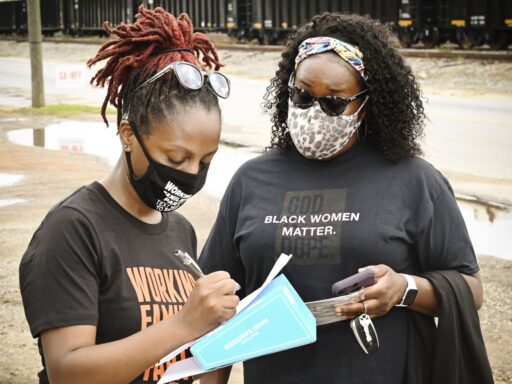

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22026529/GettyImages_1229501090.jpg) Melina Mara/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Melina Mara/The Washington Post via Getty ImagesVox spoke to six organizers active in the state to learn about the work that led up to this election — and that continues with two runoff races in January that could tip the Senate to Democrats. They have lessons for both parties when it comes to the role of grassroots organizing in winning elections, the importance of talking to people in person (even during a pandemic), and the need for politicians to make Black voters a priority — and not just right before the election. As Scott put it, “Do not take Black women for granted.”

Deborah Scott, executive director, Georgia Stand-Up

What they do:

Describing itself as a “think and act tank for working communities,” Georgia Stand-Up works on transit, affordable housing, and other issues as well as voter engagement, mostly in Black and other communities of color.

How they got out the vote:

When the pandemic began, Georgia Stand-Up initially moved its voter registration drives online. But when mutual aid groups began coming together to help people get food and other necessities, the group saw an opportunity: “If people were already going to leave their house and go to these places, we should be there to make sure they’re registered to vote as well,” Scott said. Stand-Up started doing registration at food giveaway and Covid-19 testing events, and even hosting some food giveaways of its own.

The protests this summer were an opportunity, too. When they went out to march for racial justice, members of Stand-Up wore T-shirts with QR codes for voter registration printed on the back. “Even as we’re marching and protesting, it’s like, do you want power? This is how you get it,” Scott said.

Georgia Stand-Up also made a big push to encourage early voting this year — and to help people stay in sometimes-long early voting lines. They dispatched vans to polling places around the state, loaded with everything from food to hand sanitizer to rain ponchos, part of a program started in 2009 called Voter Care. They even hosted outdoor parties at polling locations with DJs and street performers. “We just tried to make the experience of staying in line and working for your democracy a fun process versus a dreaded process,” Scott said.

For the Senate runoff elections in January, Stand-Up will be urging people to vote early again; they can do so in person starting December 14, while absentee ballots will be mailed starting November 18. The group also operated a 70-person phone bank, half calling from home and half working from a socially distanced office, during the general election, and plans to spin it up again for the runoff. “Our campaign will be geared toward ‘the democracy is not there until you finish the job,’” Scott said.

Their lessons for 2021 and beyond:

“We always knew that Georgia could flip,” Scott said. What’s more, “this is a tipping point for the rest of the South,” which is changing swiftly as younger Black people move to the region, she explained.

But when it comes to reaching voters in this rapidly changing state in future elections, parties and campaigns need to trust Black women organizers, Scott said. “We tend to be the base of what’s happening in the community.”

That includes listening to organizers on matters of strategy, like the role of in-person outreach. “Everything can’t be online for us because there’s a certain level of our population that does not respond there,” Scott said. Overall, it’s about “making sure people really listen to the wisdom that we have because we’ve lived it.”

Britney Whaley, senior political strategist, Working Families Party

What they do:

The Working Families Party is a progressive political party, running candidates who support causes like fair wages and criminal justice reform.

How they shaped the election in Georgia:

The Working Families Party recruits, trains, and endorses candidates not just with a progressive agenda but with a “people-powered” approach to governance in mind, Whaley said. “When we get people elected, they’re people who come from our communities, they’re highly accountable, they’re grassroots leaders, and we know that the conversation changes from, ‘Do you deserve $15 an hour and a union?’ to, ‘How can we make this happen?’” Whaley said.

This election cycle, the party began working with many of its candidates back in February. And it’s not just about nationwide or even statewide races. In Georgia, the party endorsed candidates like Dr. Tarece Johnson, who won a seat on the Gwinnett County School Board, where four out of the five previous members were white. And while school board races don’t usually get national attention, they’re crucial for causes like getting police out of schools and ending the criminalization of children of color, Whaley said. “All of these things are intertwined.”

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22026533/GA_WFP_Rally.jpg) Courtesy of Working Families Party

Courtesy of Working Families PartyTheir lessons for 2021 and beyond:

While changing demographics matter, a big part of Democrats’ success in Georgia this year was about the long-term work of organizers on the ground, Whaley said.

And it’s not just about groups like the Working Families Party that work directly on elections. Activists in the Movement for Black Lives, the Sunrise Movement, the Rising Majority, and smaller mutual aid and other organizations around the state “aren’t captured in this story of electoral politics, nor do they probably desire to be, but they are definitely informing how we move in electoral politics,” Whaley said.

For the future, Whaley says parties and candidates need to invest in Black communities over the long term. Today, candidates often come into these communities to campaign right before an election — “and then there’s nothing,” Whaley said. “It’s like radio silence after Election Day.”

Instead, campaigns need to invest the same kind of energy they’ve spent trying to understand and court the votes of white rural voters, Whaley said. “You need to be looking at Black voters and people of color and saying, ‘We need to make sure we excite them — give them something to vote for.’”

Overall, Whaley is hopeful for the future but emphasizes the work remaining to be done. “We beat fascism, we beat Trumpism, and we’re going to get these two Senate seats,” she said. But, “2020 is just the start.”

Helen Butler, executive director, Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda

What they do:

Founded in 1998, the Georgia Coalition for the People’s Agenda (GCPA) aims to improve governance through civic participation, using voter registration, education campaigns, and more.

How they shaped the election in Georgia:

Like other groups in the state, GCPA works on voter registration, and has registered more than 50,000 people to vote over the last few years, Butler said.

But one thing that’s unique about GCPA is its weekly Tuesday afternoon meetings, open to the public, where attendees talk about strategy and important issues in their communities. This year, many of those meetings took the form of Zoom candidate forums, where Georgians — anywhere from 50 to 100 each week — could ask questions of people running for state and local office. “We don’t tell people who to vote for or anything like that, but we bring these people before them so that they can make informed decisions,” Butler said.

The group has also been involved in challenging voter suppression tactics in Georgia, filing suit in 2018 to challenge a restrictive voter registration policy in the state that many said disproportionately impacted voters of color. Georgia ultimately rolled back the policy, but fighting such efforts takes up a lot of organizers’ time and energy, Butler said. “You take away your resources, whereas I could be doing something else.”

Their lessons for 2021 and beyond:

Groups like GCPA help drive turnout in Georgia because they connect elections to people’s daily lives. Voters might see commercials slamming Trump, for example, but they don’t explain how Democrats are going to fix problems that matter to them. A winning campaign is “not about an individual, it’s about your everyday life and how that public policy will drive what you do in life,” Butler said.

And the lesson for everyone from Georgia’s showing this year is that “we have to meet people where they are,” Butler said. “We can’t always meet them through the airwaves; we have to sometimes touch, we have to feel.”

The bottom line: “Just show an interest in the people,” Butler said. “The people is what makes the United States.”

LaTosha Brown, co-founder, Black Voters Matter

What they do:

Black Voters Matter is a nationwide group established in 2016 to build Black political power and the capacity of Black-led organizations.

How they shaped the election in Georgia:

The group works with more than 40 grassroots groups in the state, providing funding and coordination for get-out-the-vote efforts. That includes helping smaller groups purchase voter data files for text- and phone-banking, which can cost thousands of dollars. It’s about “giving them access to the tools, the technology, and the training, so they can actually build power as they see fit in their communities,” Brown said.

Their lessons for 2021 and beyond:

At Black Voters Matter, “We have always been saying that the South is not red, the South has been underinvested,” Brown said. “If you actually take the time to invest resources in the South,” she explained, “you can get a return.”

For campaigns hoping to build on Democrats’ gains in Georgia, one key takeaway is the importance of on-the-ground work, not just TV ads, Brown said. Another: “Make the campaign about the people, not about you.” The work of Black Voters Matter isn’t about getting people to follow some messianic leader, she said. Like the GCPA’s Butler, she believes it’s about “getting people to believe in their own power.”

Amber Bell, program director, Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education

What they do:

The Southwest Georgia Project for Community Education works on food security, issues facing family farmers, and civic engagement in southwest Georgia, a heavily rural part of the state.

How they shaped the election in Georgia:

The group always does grassroots organizing and voter canvassing, but this year, with help from larger groups like Fair Fight, Black Voters Matter, and the Working Families Party, they were able to take their activities to a new level, Bell said. “If we felt like a voter had been intimidated or that something was going on, we were able to pick up the phone and there were a network of attorneys, a network of organizers, and a network of supporters that could offer their support.”

Their lessons for 2021 and beyond:

All the cooperation paid off, Bell said. “When people work together and their end goal is all the same, the results are more effective.”

In particular, groups working in Georgia had learned from previous elections about the barriers that keep marginalized people from voting, whether it’s long lines or lack of a ride to the polls. “We learned lessons and put systems in place to make sure they could vote this election,” Bell said.

The runoffs in January will be a harder task because turnout typically decreases in runoffs. But the Southwest Georgia Project and others are already at work getting out the vote in that election, Bell said: “We never took a break.”

Tamieka Atkins, executive director, ProGeorgia

What they do:

A statewide coalition, ProGeorgia helps more than 30 grassroots groups around the state — including the GCPA, as well as groups like the Georgia AFL-CIO and the Georgia Association of Educators — work together on voter registration and issue organizing.

How they shaped the election in Georgia:

Founded in 2012, ProGeorgia has helped register more than 100,000 voters — more than 83,000 in 2016, more than 50,000 in 2018, and more than 20,000 this year, despite the pandemic, Atkins said. One of the group’s main strategies is helping its grassroots partner organizations embed voter registration into their everyday work — such as English classes or help with citizenship issues — for years. Making get-out-the-vote efforts part of larger community work is more effective because it’s not “transactional,” Atkins said. “It is a natural outgrowth of the conversations and the relationship-building that you’re already doing.”

After the pandemic began, ProGeorgia sent its partner organizations what it calls “civic care packages” full of masks, cellphones, tablets, and even laptops — everything they needed to continue registering voters online. “We don’t want anyone to have barriers to voter engagement,” Atkins said.

Their lessons for 2021 and beyond:

One of the biggest lessons of 2020 is “you cannot expect national entities, DC-based organizations, to do real, authentic work in states,” Brown said. That means campaigns need to get comfortable with “trusting the leadership in states to really know what they need to engage their voters.”

And now that Biden and others are thanking Black women voters for delivering the election for Democrats, they also need to look to Black and other women of color when it’s time to make key appointments in the new administration, Atkins said. And that administration needs to prioritize issues that matter to Black women, from health care to the minimum wage.

“When Black women thrive, so does the rest of the country,” Atkins said. “This can be looked at as a selfish investment.”

Author: Anna North

Read More