Social media depends on engaging content. Conspiracy theories are engaging. This problem isn’t going away.

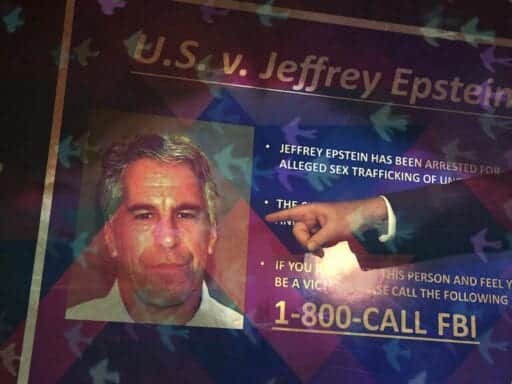

After convicted sexual predator Jeffrey Epstein died by suicide in jail this past weekend, conspiracy theories surrounding his death almost immediately jumped to the top of Twitter’s trending recommendation page. #ClintonBodyCount and tweets mentioning the Clintons — and the baseless conspiracy theories that the Clintons have orchestrated many murders over decades — were widely circulated on Twitter, a major gathering place when news breaks.

Conspiracy theories, and their ability to spread at lightning speed, are what happens when some of the worst aspects of human psychology are amplified by the internet. We keep seeing this happen over and over.

After the school shooting in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, the No. 1 trending video on YouTube falsely claimed that survivor David Hogg — who has been outspoken in support of gun control — was a paid actor. After the mass shooting in Las Vegas, in 2017, Google featured in its “top stories” a 4chan forum — an anonymous message board notorious for fueling conspiracy theories — that misidentified the shooter as a Democrat with ties to leftist, anti-fascist groups.

We now know why many people believe in, or are attracted to, conspiracy theories. Psychologists have found conspiracy theories are a tool to quell anxiety, give people a sense of control, and help make sense of a complicated, depressing, and often disappointing world. “It’s a self-protective mechanism,” Jan-Willem van Prooijen, a top psychological researcher studying conspiracy theories, told me in 2017. It’s often easier — and more comforting — to believe in an elaborate neatly tied-up lie than to deal with the truth.

Humans aren’t perfectly rational thinkers, so conspiracy theories — and their bedfellows, superstitions — aren’t anything new.

What is new, and concerning, is how fast they can now spread. Our online media ecosystems seemed designed (intentionally or not) to promote them over real news stories in the wake of breaking news.

“With each news cycle, the false-information system grows more efficient,” New York Times opinion writer Charlie Warzel noted. The more a conspiracy theory is publicized, the more it becomes harder to stamp out. And it doesn’t help that we have a president who routinely endorses, or retweets, conspiracy theories, ensuring they stay in the public eye even longer.

The FBI now even considers conspiracy theories to be a domestic terrorism threat, as more people are driven to violence by them. It doesn’t take spreading misinformation to a lot of people to cause a lot of damage. Most people vaccinate their kids, for instance. But the ones who don’t are fueling a worldwide resurgence of measles.

How do social media platforms want to respond?

Why conspiracy theories are so compelling for certain people

Research has found that some people are just more prone to believing in conspiracy theories than others. And it’s not because these people are necessarily unintelligent (though being more analytical is correlated with being less swayed by conspiracies.)

People who feel powerless and who are more pessimistic are also more likely to believe in conspiracy theories. The theories “serve the need for people to feel safe and secure in their environment and to exert control over the environment,” a recent review of the field of conspiracy theory psychology, explains. They’re also a type of motivated reasoning. If conspiracy theories about Epstein’s death make the Clintons look bad, people on the right are going to be more likely to embrace them.

Our minds can twist facts to make us feel good, or to support our political teams. “What makes the conspiracy theories so frustrating,” my colleague Dylan Matthews writes “in part, is that they’re premised on real elements: credible accusations of sexual misconduct against Bill Clinton, Clinton’s real ties to Jeffrey Epstein, and Epstein’s own well-documented sex crimes. It doesn’t take incredibly inventive conspiracy theorizing to move from that to allegations that Clinton was part of Epstein’s sex abuse and from there to wild accusations that Clinton had Epstein killed.“

Another simple, infuriating, finding in psychology: The more we hear a piece of information repeated, the more we’re likely to believe it. Each time we hear a story, the story grows more familiar. And our brains tend to confuse familiarity — or salience — with truth.

Again, this is human, and to be expected. And it’s something social media companies need to deal with.

False news is always going to move faster than the truth

In 2018, scientists at MIT published a study that’s instructive on this issue, and makes me wonder if false news and conspiracy theories are a problem tech platforms can ever really solve. The study analyzed millions of tweets sent between 2006 and 2017 and came to this conclusion: “Falsehood diffused significantly farther, faster, deeper, and more broadly than the truth in all categories of information.”

Perhaps even more important is what the study reveals about what’s responsible for fueling the momentum of false news stories. It’s not influential Twitter accounts with millions of followers, or Russian bots designed to automatically tweet misinformation. It’s ordinary Twitter users, with meager followings, most likely just sharing the false news stories with their friends. “Falsehood reached more people at every depth … than the truth, meaning that many more people retweeted falsehood than they did the truth,” the study found.

That is: There’s no conspiracy about why false news, or conspiracy theories easily spread. It’s because people find them compelling, and share them.

“Fake news is perfect for spreadability: It’s going to be shocking, it’s going to be surprising, and it’s going to be playing on people’s emotions, and that’s a recipe for how to spread misinformation,” Miriam Metzger, a UC Santa Barbara communications researcher told me last year.

This is the problem with getting news from Twitter, Facebook, Google, or YouTube. So often it arrives in our feeds filtered through the human emotional system. The most viral tweets are the ones that tug on our heartstrings. And conspiracy theories, and false news is often designed with this in mind.

Platforms are under more and more pressure to potentially censor, and regulate dangerous misinformation. Earlier this year, Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube took some small steps to crack down on anti-vaccination info.

But it’s still the case that these platforms exist to serve people engaging information. And it’s still the case are engaged with conspiracy theories, like #ClintonBodyCount. Is censoring the spread of breaking misinformation even possible for these platforms? It remains to be seen.

Author: Brian Resnick

Read More