The new West Side Story is led by a brilliant cast. But its reinventions don’t always work.

With “indoor kid” the new trend of the season, and New Yorkers and tourists alike opting to stay home with one eye on the coronavirus news, Broadway theaters are staying open — and trying to figure out ways to bring in audience members, too. Stalwarts like The Lion King are seeing their ticket sales drop to post-9/11 levels, and Frozen’s ticket returns dropped by $126,000 last week. Now, Broadway mega-producer Scott Rudin is lowering the price to $50 on the unsold tickets to every show he currently has on the Great White Way, including Ivo van Hove’s controversial new West Side Story revival.

Is it immoral for an industry whose customer base is mostly older people, the population most likely to be affected by coronavirus, to try to bring in audiences at the probable expense of public health? I am no bioethicist, but it seems like the answer is probably yes! Should you choose nevertheless to roll the dice and show up to see West Side Story at the Broadway Theatre — which smells so strongly of bleach right now that walking into it is like wading into a swimming pool — here is what you will get.

West Side Story is one of those shows that is simultaneously so immortal and so dated that to radically re-stage it in 2020 feels like an act of hubris. Why do we need another version of “Tonight” or “The Dance at the Gym” when the ones we have from the original 1957 Broadway staging and the 1961 movie are already perfect? And what could you possibly do with that script full of daddy-os and buddy-boys and racial caricatures that would feel fresh and urgent today? Traps loom everywhere you turn.

Nonetheless, 2020 will see the premiere of two new West Side Stories. In December, Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story will hit the big screen. And since its debut on February 20, West Side Story is on Broadway in a new revival directed by Ivo van Hove.

The problems of staging West Side Story in 2020 are exactly the kind that would appeal to van Hove. He’s a Belgian director who emerged onto the New York theater scene from the Netherlands in the late ’90s, and he has managed to keep on being described as “avant garde” in reviews like this one, even after he’s mounted multiple successful Broadway shows.

Among his fans, van Hove is known for breaking down classic American stories, shows like The Crucible (on Broadway in 2016) and Angels in America (at the Brooklyn Academy of Music in 2014). He’s known for freeing works from the shackles of naturalism, stripping his shows to their component parts, and revealing new angles to stories we thought we already knew. Van Hove skeptics, meanwhile, argue the director’s aesthetic has begun to calcify into schtick, a collection of tricks and nothing more: empty minimalism, meaningless video projections, and a grinding sense of misery.

On one level, van Hove would appear to be a perfect fit for a show as iconic, American, and specifically rooted in time as West Side Story. And on another level, he looks like the worst possible fit.

Van Hove’s West Side Story doesn’t prove either camp right about him. It’s an ambitious, only partially coherent production that is disappointing mostly for being just a little bit boring.

This West Side Story has a mostly great cast. But van Hove’s reinventions let them down.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/19785866/6080_Yesenia_Ayala_and_the_cast_of_WEST_SIDE_STORY_Photo_by_Jan_Versweyveld.jpg) Jan Versweyveld

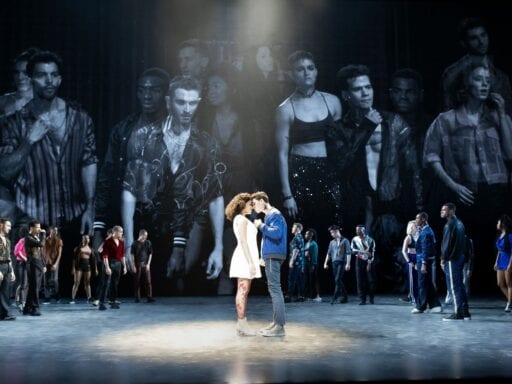

Jan VersweyveldRemoved from van Hove’s West Side Story are the following: the charming and sprightly “I Feel Pretty;” Jerome Robbins’s iconic finger-snapping choreography; the fire escape from the fire escape scene; the all-white Jets; the 1950s setting; and much of Arthur Laurents’s book.

Added: A massive video screen backdrop on which is projected intermittently closeups of the onstage action or black-and-white slow motion footage of the actors cavorting down empty streets. Surprisingly conventional new choreography from the iconoclast Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker. Jets made up mostly of black actors. A few smartphones. So, so many neck tattoos.

The videos are what you notice most. As the Jets make their first entrance, staring out of the vast, bare stage in a row, a camera from somewhere in the audience zooms into their faces, which swim up onto the mirrored backdrop behind them.

Later, doors will swing open in the mirror to reveal tiny dollhouse sets: Doc’s drugstore, the sweatshop where Maria and her family work. They’re set into the mirror, so we can’t see them fully from our seats. Instead, when the cast goes inside, camera operators slip inside with them, and we see their movements splashed onto the backdrop around the doors, a split second out of sync with the audio.

The video is a cinematic effect for this theatrical space, giving us the wide shot and the closeup at the same time. It’s a standard van Hove technique, and here, it’s only partially successful. It’s fantastic at making the stage violence feel real: When a Shark slices open a Jet’s ear, we see the blade lower and the ensuing blood spurt in so much detail that the stakes automatically feel high.

But West Side Story lives and dies by its heightened, operatic emotions, but video only ever distances us from them. Whenever the able young cast is projecting to the last row of the theater, the video shows the artifice of their movement, and whenever they scale their reactions down enough for the video to read as naturalistic, they vanish from the stage. Somehow, we are always presented with their worst angles.

That’s a particular shame with this West Side Story cast, which is by and large very good. Even van Hove detractors will admit that he can always pull good performances out of his actors, and there’s an earnest sweetness to this young cast — 33 of whom are making their Broadway debuts — that goes a long way in balancing that stark, empty stage.

Particularly strong are the lovers. Shereen Pimentel brings a grounded and earthy presence to her Maria that she contrasts beautifully with a pure operatic soprano; her Maria is young and sheltered, but she isn’t naive. Pimentel’s strength makes the loss of “I Feel Pretty” hurt all the more . Without that showcase, Maria is relegated to duets, but you want to see what Pimentel could do with a solo.

As Tony, Isaac Powell runs away with the show. He moves with a nervy, scrappy sincerity: When he spins in ecstatic circles across the stage during “Tonight,” you believe he’s fallen in love, but you also believe him when he launches himself into the rumble between Jets and Sharks. And when he holds himself still during the deceptively simple “Something’s Coming,” nervous energy pours off him in waves. After that setup, you understand exactly why “The Dance at the Gym” turns into a hormonal pressure bomb.

But when you turn away from the leads, you run into West Side Story’s casting controversy. Amar Ramasar, who plays Bernardo, was briefly fired from New York City Ballet after trading sexually explicit photos of other dancers without their consent with another company member. (An arbitrator later ruled that Ramasar should have been suspended rather than fired, and he was brought back into the company.) Protesters have demonstrated outside the theater, and they’ve generated an online petition to see Ramasar fired from West Side Story, but producer Scott Rudin has maintained that the show will stand by him.

Onstage, Ramasar’s Bernardo seems not remotely worth the trouble. His fake Spanish accent is cheesy, and although he leaps and spins with elegant balletic lines, he tends to fade into the background even during dance numbers. Yesenia Ayala, the triple threat who swishes her ponytail across the stage as Anita, eats him alive.

Dating West Side Story most, even more than its frequent and unironic use of the word “daddy-o,” are the racial politics. The Puerto Rican Sharks are written as cartoons, sentimentally and without specificity, and even when they shout, “Mambo!” during “The Dance at the Gym,” the music they dance to is never rooted in actual Latin rhythms.

This version of West Side Story, although it ostensibly takes place in modern day, is not particularly interested in fixing that problem. (It’s worth noting that the dance company did succeed in getting De Keersmaeker to let them develop a Latin dance vocabulary for certain numbers.) Van Hove has diversified the traditionally all-white Jets with a majority black cast. But that’s a muddled change: Why do the black Jets seem to feel more solidarity with their white fellows than with the Puerto Rican Sharks?

And when the comic vaudeville number “Gee, Officer Krupke” turns into a meditation on police brutality, the choice just feels overly literal and didactic. The critique of the police was there in the song all along; we didn’t also need shaky cam video footage of cops arresting disenfranchised youths playing in the background to get that.

But Van Hoves has never been all that interested in or good at talking about race in America. What he is supposed to be actually good at — what his special genius as a director is supposed to be — is finding the new and unexplored angles in all the classic stories we thought we already knew.

His West Side Story never quite gets there. It offers us a luminous and tender love story on the strength of the performances from Pimentel and Powell, and the videos give us a spectacularly violent landscape of gang warfare.

But we already knew that West Side Story was both tender and violent. We also already knew that about Romeo and Juliet, its source material. That is, in fact, what both of these stories are famous for. And Van Hove’s version is not tender or violent in any particularly new, exciting ways.

So in the end, all that experimentation, all that stripping away and building back up, ends in a faint sense of anticlimax. Van Hove’s West Side Story is perfectly fine. But it fails to offer us a compelling reason for it to exist.

Author: Constance Grady

Read More