The Oscar-nominated director of Attica keeps showing us the real America.

I was a teenager when I watched Sidney Lumet’s Dog Day Afternoon, and I had no idea what Al Pacino was yelling about outside that bank. “Attica! Attica!” made me curious, but there was nothing about it in my high school textbooks and not that much in the library. I’d have to wait many years to understand more about the largest and deadliest prison insurrection in United States history.

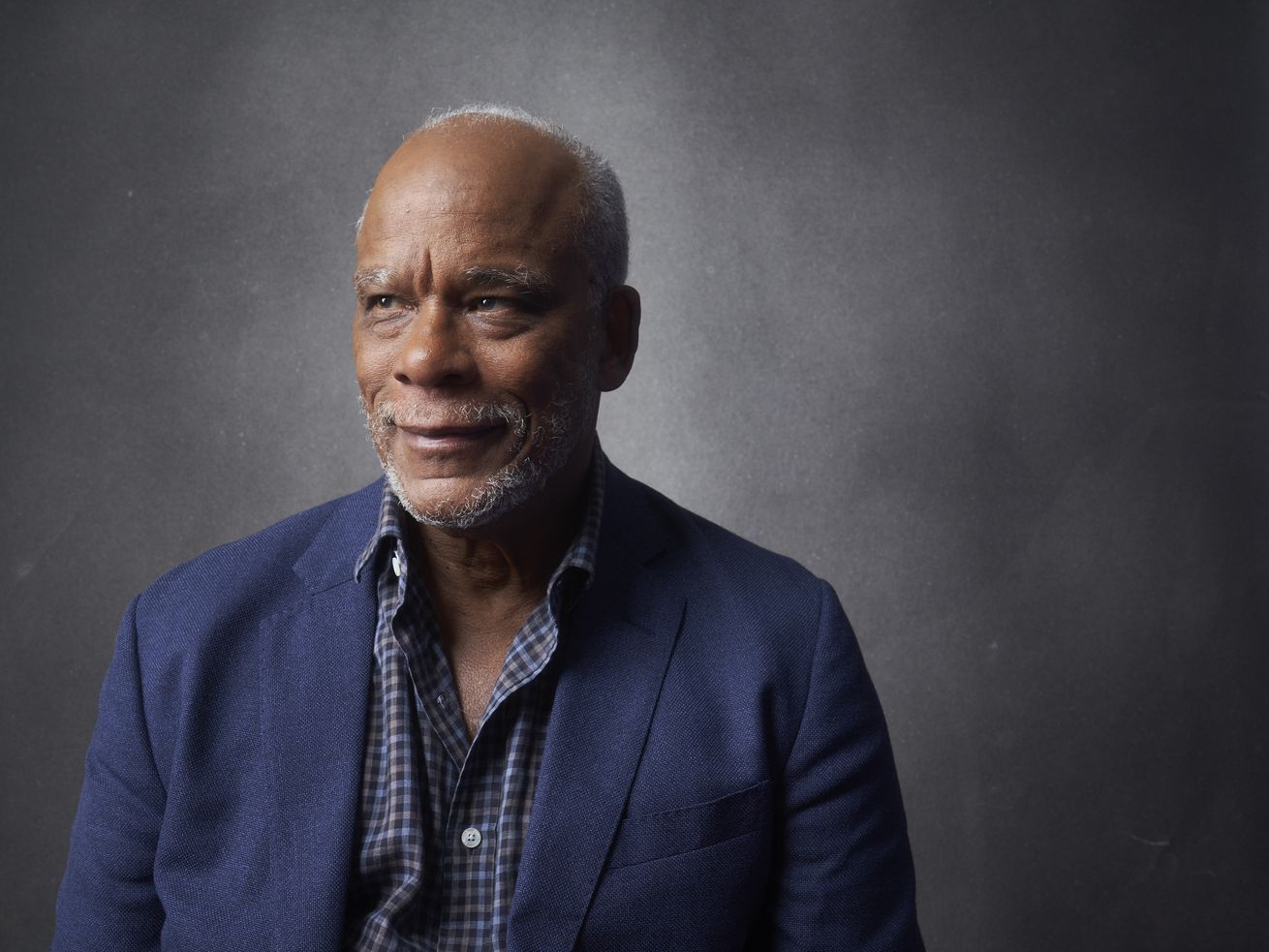

Amidst a conservative crusade to criminalize the teaching of that history, there may not have been a better time for documentarian Stanley Nelson’s Attica to emerge.

During much of the three decades Nelson has spent making films, he has told stories about Black life in America. His films have shed new light on everything from the 1921 Tulsa pogrom to the fight for civil rights in the 1950s and 1960s, with films such as Freedom Summer and The Black Panthers: Vanguard of the Revolution. Now, the 70-year-old documentarian has received his first Academy Award nomination for his feature-length look at one of the most pivotal events in the history of American criminal punishment.

Co-directed by fellow nominee Traci A. Curry (a friend and former colleague of mine), the documentary begins with the inception of the rebellion — an explosion of the frustration building up in the men imprisoned at Attica Correctional Facility. The persistently poor treatment they were receiving ranged from insufficient medical care to a lack of showers and toilet paper. The disrespect and dehumanization by the all-white roster of guards may have been at the top of the list. The prison’s population has a heavy majority of Black or brown men so, as one interviewee asked sardonically early in the film, “What could go wrong?”

One answer to that question came on September 13, 1971, five days after the standoff began. State police retook the prison, using gunfire. Thirty of the 33 incarcerated men who died that week were killed by law enforcement. Though a cover story emerged that alleged the prisoners were responsible for all 10 deaths of Attica prison guards during the insurrection, medical examiners quickly determined that authorities killed nine of them.

As the film details, authorities also hunted down many of the insurrection’s leaders. The captive insurrectionists who survived were held at gunpoint in the open yard. They had been stripped completely naked and lined up. The image evokes captives huddled together in the hull of a slaver’s ship, or placed in line before being auctioned off like cattle. Dehumanization of the prisoners by authorities sparked the insurrection, and their punishment was an even more accelerated version of it.

It’s perhaps the film’s most striking image, and it’s where I wanted to start my conversation with Nelson. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

I’ve always believed nothing is truly comparable to chattel slavery except chattel slavery. But those images of the incarcerated men, those who survived, standing and sitting naked out in the yard…

Had you seen that before?

I just saw it for the first time making the film. My reaction was: Oh, shit. Wait a minute. Are these pictures real?

One of the strange things is that so many times, the footage acquires its real power from the way it’s edited in the film. When you see [the naked men] in context and people talking about that they were made to strip all their clothes off and just sit there with their hands on their head, stark naked. Then those pictures gain even more power.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23337861/Attica_0024_R.jpeg)

Courtesy of Showtime

This is your first Oscar nomination after directing more than 25 films, and I know you’ve produced many more. What does this particular recognition mean to you? I know there are other accolades — you won the DGA (award for Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Documentary) — but an Oscar nomination … what does that mean to you?

Well, the Oscar was always the biggest. It’s just so special. I remember, as a kid, watching the Oscars with my mother and just being fascinated by all the gowns, the movie stars, that whole thing. It’s just really huge.

Just being nominated draws so much more attention to Attica and so many more people will see it. The Oscar nomination is like a stamp of approval. It’s really big for me personally, but it’s even bigger ’cause it means more people will now see the film.

Also, it isn’t as if one necessarily has to see it in the theater. People can pull it up on Showtime and YouTube. There’s more accessibility to the material you’re putting out there.

The accessibility of my films and all films has changed the industry, especially for documentaries. People who might not go to the movies to see a documentary call one up at any time and see it. They can say, “Hey, honey, we’re tired of watching people swing on webs — let’s try a doc.” And without costing them any money. They can watch the first five or 10 minutes and see if they wanna proceed.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23337886/Attica_0006_R.jpg)

Courtesy of Showtime

I’d like to talk more about how the film begins, with the very first moments of the rebellion — including the violence done to (and care for) William Quinn, the only guard who died from injuries caused by the men incarcerated at the prison. And it tells us about the poor treatment that inspired the insurrection.

Having done a number of historical films, one of the hardest things to do is to tell what we call the backstory. Why did the prisoners rebel? What was happening in Attica? So many times, we kinda have to leave out that history because you gotta get to the story.

With Attica, we had this little historical segment that talked about the town of Attica, New York — and then [another in which] they talked about the mistreatment of the prisoners. We didn’t know where to put it. We actually tried to put the history unit first, and it was like, “I thought we were talking about a rebellion in the prison. Why are we talking about this town?”

Then we found this great piece where “L.D.” Barkley, one of the prisoners, is talking into the mic after the rebellion starts on the first day. And he says, well, you wanna know why we’re here? We’re here because of the mistreatment that we’ve been [subjected to] in the Attica prison. And it seemed the perfect way to go back in time. So we started the film, immediately, with the rebellion and that seemed to work. If the story of the rebellion was exciting enough that first day, you wouldn’t be sitting there wondering, “Well, why did they rebel?”

You’re a New Yorker, and I’ve lived in New York before for many years. The Attica prison and the rebellion were things that you heard about, that you knew about. But there are folks who just have no frame of reference whatsoever.

I think one of the things that we had to do with this film is it had to play to everybody. So that there were people like yourself who knew the broad outlines of Attica or [just] some of the details. There are people who don’t know anything about Attica. I mean, I can’t tell you the number of people, when we say “Attica,” they’re like, “Oh, so what’s that? Is it a type of dog? Is it a place? Is it a thing?” We had to make the film make sense to everybody and also hold everybody’s attention.

Yeah. And that’s the thing: It’s tough to know necessarily what everybody would want or need. Do you feel like there has been a change in how your films, including this one, are received as time has passed?

In a way, I think that Attica definitely has been received in a different way than it would have, like three or four years ago. Because of George Floyd, because of the protests against the police, because we’ve seen — over and over and over again — the police violence against people of color. The door is cracked open a little bit for people.

The people who are interviewed in Attica are all so incredibly convincing — from the prisoners to the news people, to the hostage families, to the observers, to the National Guard. You don’t doubt for one second that anything they tell you is the truth.

I’m interested in what you knew of the truth before. Can you describe what Attica signified to you and to other Black people in New York City well before the rebellion, particularly before the massacre happened?

I was 20 years old when Attica happened. I was old enough to remember it. It was like a thriller story: the prisoners had taken over this prison, what’s gonna happen? What’s gonna happen through five days? And then finally, devastating that it ended with such incredible violence that nobody thought it would end in. Nobody thought that they would just go in with guns blazing and kill [nearly] 40 people.

So, I think that for so many people, especially in New York, Attica came to symbolize the power law enforcement [has] and the willingness to use that power to put down any kind of rebellion in the most violent way. Attica became really a symbol of the power that is [in] rebelling: The power that the prisoners had to rebel, and then the power that the state would take, and the violence that the state was perpetrating on people who rebelled against it. Because there’s probably no one more powerless than prisoners in a penitentiary.

We didn’t know anything about Attica. It was an upstate prison, 250 miles from New York City. Unless you were involved in the prison system or you had a loved one in the prison system, nobody talked about it or thought about it.

I mean, that’s what prisons are made to do. That’s one reason why prisons are in the middle of nowhere. We don’t have to see it day-to-day and we don’t have to think about the prisoners and that’s what prisons are set up to do. So we don’t have to think about the prisoners and the fact that we’re incarcerating more than 2 million people. We don’t have to think about it.

What did you learn about the rebellion and the massacre during the process of filmmaking?

I learned, one, why the rebellion started. We never really understood why the rebellion started, how cruel and unusual the punishment was. Why they felt that they had to rebel. The vast majority of people never quite understood the ins and outs of why [New York Gov. Nelson] Rockefeller ordered them to go in and use deadly force. We learned that in the film, through interviews that we did. The phone calls [with President Nixon], which are just really shocking.

I knew about the incident, but I didn’t realize the political consequences for Rockefeller’s career that stemmed from that. I knew him as the vice president under President Ford. I had actually not really understood how this incident really helped embolden his power.

Propel him to go to be vice president, yeah.

You’ve spent a great deal of your career, Stanley, telling various stories about Black experiences. Profiles of people such as Madam C.J. Walker, Marcus Garvey, and the Freedom Riders. You’ve looked at tragedies like Tulsa, as well. How has making these films changed how you personally look at America, if at all?

I think that one of the things it’s done for me is it’s helped me to understand that — that America’s like a roller coaster ride, you know?

[laughs]

Sometimes up and sometimes down, on this back up and there’s down again. And a lot of times we, especially, as African Americans, wanna look at the idea of “up from slavery.” Slavery was the worst, and now, it’s upward progression into the light. But it is really a roller coaster ride. There’s times when [it’s] at the top and there’s times when it goes down to the bottom. But it stays at the top much longer as long as we push. That’s not only African Americans, but [all] people of color. As long as we push for change, at least we’ve got a chance.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/23337900/Attica_0046_R.jpg)

Courtesy of Showtime

As the documentary makes clear early on, the physical structure of Attica aided the insurrection in the first place. How did you make decisions about the film’s structure, the graphics that you use, archival footage, to illustrate points such as that most effectively?

You as an audience had to be aware of the physical structure of the prison. That you had to be aware of where you were in time. And then, we could really concentrate on the kind of roller coaster ride, which was every day, of Attica.

You had to understand that they were trapped in one yard in the prison and that there were guys with guns on the walls, trained down at them, for five days. And that the only thing that held [those guns] off was the fact that they had hostages.

And you needed to understand that every day was different. And so, we have a very simple five-day structure to most of the film. The exhilaration of the first day. The despair of the fourth and, then, the morning of the fifth day. We really wanted to have a framework so that you could understand that much easier.

How did all the technical expertise that you’ve acquired over the course of your career help audiences to comprehend a story like this in full?

We made the film during the time of Covid. So many of the archives were closed down and we just had to wait and keep calling. Find people’s home phone numbers, sometimes to call at home and see what we get. [We had] to be tenacious.

We made a couple decisions early. I made a number of films in the last few years without narration, and we thought that we could make this one without it. I think it kind of makes the audience see the film in a very different way. So we don’t have anybody, like the “voice of God,” telling you what to think.

We had thought that we would need historians to talk about it. We actually filmed one historian and cut together a couple of scenes, and he was great. But we realized that we didn’t need them. We would let the story all be told by people who were there.

And we realized early that we just wanted the music to kind of be a wind at the back of the story. We didn’t want the music to take over. That was really complicated because we had to really cut back on the drama, on how loud the music was. The story’s just so amazingly dramatic in and of itself, and we didn’t wanna send it overboard.

Some of the logistical challenges you alluded to with Covid, I mean … I’ve spent a lot of time digging through archival footage during my career. How much do you enjoy that particular part of the filmmaking process, if at all? ’Cause I know so many people don’t get to see that.

I love watching old film. Finding archival material and looking at old pictures. And I never knew that [before]. It wasn’t like I went into filmmaking, and made a bunch of historical films ’cause I was like, “Oh, I love looking at old films and seeing old pictures.” But I just really do. I love it. I love looking for the details.

Think [about] when the helicopters come in on the final day. They fly over and they’re gonna go into the prison. There’s a shot of the families outside and these three or four women, and they all look up.

I mean, it’s just as if you were directing a feature film. All those kinds of great things that just happened. There’s a woman with her head bowed and then the camera pans down and she’s praying, Her hands are together and she’s praying. It’s just like, “Oh, shit!” [laughs] “This is great stuff.”

It’s a matter of really loving the footage. And we really had to mine it and look at it over again.

I understand exactly what you mean. I was astonished by some of the stuff that you were able to find. I mean, the footage of the incarcerated men rolling out the injured guard, William Quinn, on a stretcher. I’m thinking, “Who was even filming at this point?”

That’s the shot. When I saw the first rough cut, when I saw that shot, I thought, “Now we’re in the prison. Let’s keep you there.” We’ve got something that’s special. It’s recognizing those shots.

Putting together a film is like putting together a puzzle without a picture of what it looks like when it’s completed, right? You just gotta figure out how it fits.

I would do jigsaw puzzles with my daughter. There’s a whole line of puzzles that are hand-cut, that don’t have a picture. They’re supposed to be impossible. You have no guide.

Talking about pictures, I’m reminded of the first image we talked about, of the naked prisoners held in the yard after the insurrection. It slaps everyone across the face.

What kind of urgency is there for you as time moves on to tell such stories while you can? And if so, how does that—

I mean, am I gonna die soon?

No, no, no, no, no. [laughs] I don’t mean it like that.

I’m not sure if there is urgency. You know, I’m truly honored to be able to tell the stories that I’ve been able to tell. I think that it’s really exciting because you know, there’s any number of stories to tell about the African American experience.

Given that, what are your thoughts about the government determining which parts of the African American experience that students can or cannot learn in school? And what parts of history are considered palatable?

[laughs] I think that it’s unbelievable. We have to really be conscious of what’s happening. Ten years ago, you wouldn’t have believed it if somebody told you what was gonna happen and what’s happening. We’re not gonna teach about the enslavement of African Americans because it makes somebody uncomfortable?

I just think that it’s really, really destructive, and it boils down to the cliché: If you don’t know your history, you’re doomed to repeat your mistakes. It’s an incredible step backward.

Author: Jamil Smith

Read More