Omar al-Bashir, an accused war criminal, was arrested by the military on Thursday.

The Sudanese military has ousted president Omar al-Bashir in an apparent coup, following months of intense anti-government protests against the long-serving dictator.

Gen. Awad Ibn Auf, Sudan’s defense minister and former vice president, announced al-Bashir’s overthrow on Thursday, telling the country al-Bashir had been arrested and that his regime had been toppled.

Ibn Auf also declared that the constitution would be suspended and the military would take control during a two-year transition period. He announced a three-month national emergency (though al-Bashir had already instituted year-long national emergency in February) and imposed a 10 pm curfew.

The removal of al-Bashir is a stunning development. The authoritarian leader took over in a coup in 1989, and has maintained his grip on power for 30 years despite international pressure over Sudan’s support of terrorism and perpetration of genocide in the Darfur region. He is wanted by the International Criminal Court (ICC) on charges of war crimes and other atrocities.

Al-Bashir also oversaw a long-running civil war between north and south Sudan, which ended in a peace agreement in 2005 and eventually led to the break-up of his country with the independence of South Sudan, in 2011.

But the military’s announcement that it plans to retain control has dampened the historic end of al-Bashir’s rule, as protesters fear this is a continuation of the regime, rather than a move toward democracy and a civilian-led government that they have been demanding for months.

“For many, it’s an in-house handover, or coup, rather than a genuine change that the people have actually been demonstrating for,” Bashair Ahmed, a doctoral researcher at Sussex University and director of Shabaka, an African and Middle Eastern diaspora advocacy group, told me.

The situation in Sudan is in flux. The Sudanese Professionals Association, which mobilized the protests, has said demonstrations will continue to until civilian leadership takes over.

But al-Bashir’s defeat is significant, and it comes just a few weeks after another long-serving ruler, this time in Algeria, agreed to step down amid widespread protests. The ousting of entrenched leaders in Algeria and Sudan just a few weeks apart has strong echoes of the uprisings of the Arab Spring in 2011.

And now, as then, both promise and peril lie ahead.

Sudanese protestors finally forced Omar al-Bashir from power

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16026416/1026073062.jpg.jpg) Nicolas Asfouri-Pool/Getty Images

Nicolas Asfouri-Pool/Getty ImagesAl-Bashir took power in a military coup in 1989, and his three decades of control has been defined by corruption and brutal violence. He ruled during decades-long civil war against an insurgency in the southern part of the country, which ended in 2005 with the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA).

But just as the conflict with South Sudan was ending (the region would eventually vote for independence, a provision of the peace agreement, and become its own sovereign country), al-Bashir faced another insurgency, this time in the Darfur region in western Sudan.

To fight that insurgency, he relied on pro-government militias — known collectively as the “Janjaweed” — who carried out heinous atrocities, burning villages, murdering civilians. (UN estimates say about 300,000 people were killed.) Al-Bashir was charged by the ICC for overseeing the genocide in Darfur, effectively making him persona non grata on the international stage.

Not that he wasn’t before. Sudan has been classified as a state sponsor of terror by the US State Department since 1993, after Sudanese government officials were found to have been directly involved in the planning and logistics of the deadly World Trade Center bombing earlier that year. Throughout the early 1990s, the al-Bashir government hosted a who’s who of terrorist groups, including al-Qaeda, Hamas, Hezbollah, and others.

That has gradually changed, and the al-Bashir government has cooperated with the US on counterterrorism efforts for several years now. In 2017, the Trump administration lifted some sanctions on the country as part of a rapprochement with Sudan’s government that began in the Obama administration.

However, the country remains designated as a state sponsor of terror by the State Department, and sanctions related to the genocide in Darfur remain in place.

A popular uprising put unrelenting pressure on al-Bashir

Protests have broken out against al-Bashir several times in previous years, including in 2011 as part of the Arab Spring. Major demonstrations also took place in 2013, and even in at the start of 2018. But those protests were primarily centered in the capital of Khartoum and were met with fierce government crackdowns.

This most recent uprising erupted in December 2018 after al-Bashir ended government wheat and fuel subsidies, causing a spike in food prices and gas shortages. But the demonstrations quickly turned into an outlet for people’s broader frustration and fury with al-Bashir himself.

And what began as breakout demonstrations became a more organized political movement, led by middle-class professionals, such as doctors and lawyers, and students. The Sudanese Professional Association, a trade organization representing those and other professions, is one of the main forces behind the current protests.

Social media also helped ignite the movement, allowing activists to connect and circumvent the state-controlled media. Access to Facebook, WhatsApp, and Twitter has brought young people out on the streets in large numbers.

Women, too — who face restrictions on where they can go and how they can dress in Sudan — have been drivers of the movement. “It’s a revolution being led by the very people being born and raised under [al-Bashir] — they’ve known no other president,” Ahmed said.

Al-Bashir tried to crack down on the protests in February, instating a year-long state of emergency that only intensified demonstrations against his government. Clashes between Sudanese security forces and protests have killed dozens since December.

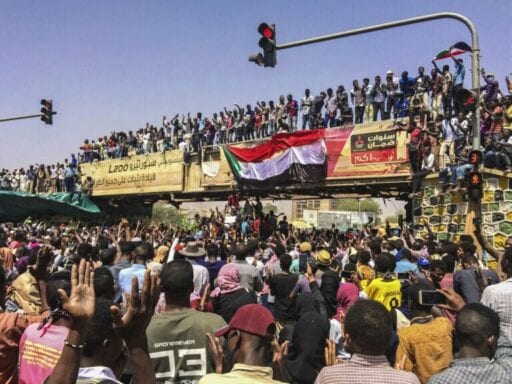

The latest round of protests began on April 6, on the anniversary of a 1985 coup that removed President Jaafar Nimeiri from power. Protesters rallied and staged a sit-in outside the presidential palace and in front of the military headquarters in Khartoum.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/16026421/AP_19097378941096.jpg) AP

APThe demonstrations continued unabated. Security forces tried to dislodge protesters earlier in the week, firing tear gas and bullets into the crowds. But army soldiers reportedly protected and defended the protesters against some of these attacks, a sign that al-Bashir’s hold on power was becoming more tenuous.

And on Thursday, a major victory: Sudanese military announced al-Bashir’s arrest — and thus the end of his decades of rule. The announcement was met with celebrations, and political detainees and protesters who had been held by the government were released.

@badreldins , out of detention, loudly chanting: Freedom, Peace, And Justice ❤️ pic.twitter.com/mqNN1fwyzt

— Walaa Salah (@WalaaAbdelrhman) April 11, 2019

But some of that jubilation was tamped down by the suddenly uncertain future for Sudan — and doubt about whether a change in leader goes far enough.

“What people want on the ground is for the whole system to change,” Amal Muntaser, a student and activist from Khartoum who’s currently in studying in Italy, told me. “Because it’s not just the president that has been part of the problem. It’s the whole regime.”

An incomplete victory, and uncertainty, in Sudan

The Sudanese military told the public it had arrested al-Bashir, and that his regime was over. It pledged it institute a two-year military transition government, with the promise that it would prepare for “free and fair” elections afterwards.

For protesters, the offer of future elections rang hollow — especially as the defense minister announced a curfew and the continuation of the state of the emergency.

Gen. Awad Ibn Auf, the defense minister who is now the de facto leader, is also deeply connected to Bashir’s regime and the Sudanese military. Auf oversaw military intelligence during the conflict in Darfur, and he was sanctioned in 2007 by the US Treasury Department for his role in perpetrating human rights abuses in the region. It alleged that Auf “provided the Janjaweed with logistical support and directed attacks.” Protesters fear Auf’s connection to the conflict in Darfur makes it unlikely he will turn al-Bashir over to face justice in front of the ICC for his war crimes charges.

Ahmed told me videos from the protests show people still in the streets chanting, “From one thief to another thief” in Arabic.

“To them it’s the same people, so I think there’s a symbolism component that Omar al-Bashir is now under arrest and not the president any longer — that’s significant, no one can say that’s not the case. But in terms of structure, what changes are people likely to see?”

That uncertainty means the protests and sit-ins are unlikely to stop, and the Sudanese Professional Association is urging the sit-in to continue outside the military headquarters.

“We shall stand our ground on the public squares and roads that we have liberated with our might, continuing with the popular struggle until state power is reinstated to a civilian transitional government that represents the forces of the revolution,” the group said in a statement Thursday. “That is our clear and irrevocable stance: the streets never betray, and we shall meet there.”

The protests in Sudan also come in the wake of the resignation of the ailing 82-year-old Algerian president Abdelaziz Bouteflika. As the world has worried about the rise of strongmen in places like Brazil and Hungary, the protests in Algeria and Sudan offer a very different narrative.

What that means for the region, and for Sudan itself, is now unfolding. How the world reacts to this uprising in Sudan will also offer some clues to the country’s future. Egypt has backed Bashir’s removal (which is kind of rich), but it’s unclear how the rest of the region — including Gulf states such as Saudi Arabia involved in Sudanese affairs — will respond.

But the protesters plan to keep fighting for democracy, which is why the military’s announcement this morning overshadowed the victory of al-Bashir’s ouster quickly. The protests offered people of vision of Sudan they wanted to see, and they’re not ready to give that up anytime soon.

As Muntaser, the student and activist, told me, one of the most powerful elements of the Sudanese demonstrations was the reclaiming of public space.

“It was hard for Sudanese people to gather in big groups and participate in public life,” she said. The protests changed that. People gathered, they sang hymns, they gave speeches.

“People feel like they still have strength,” Muntaser said. The regime “fell once, it can fall again.”

Author: Jen Kirby

Read More