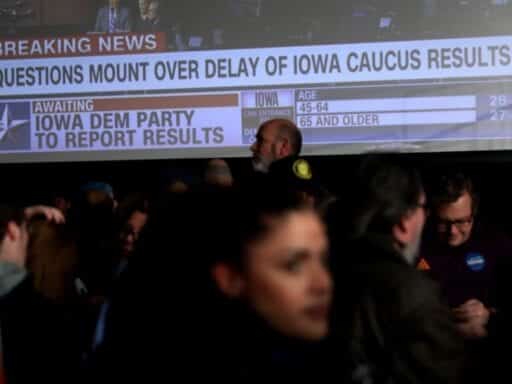

The 2020 election cycle kicks off with problems at the Iowa caucuses.

The Iowa caucuses appeared to melt down on Monday night after multiple reports of technical difficulties related to precincts reporting results in Iowa. It’s so far unclear how the problems started or if the cybersecurity threat is more serious.

So far, details about the issues are sketchy, but it does sound serious enough to alert all of the campaigns. Iowa Democratic Party communications director Mandy McClure later issued this statement:

We found inconsistencies in the reporting of three sets of results. In addition to the tech systems being used to tabulate results, we are also using photos of results and a paper trail to validate all results match and ensure we have confidence and accuracy in the numbers we report. This is simply a reporting issue, the app did not go down and this is not a hack or an instruction. The underlying data and paper trail is found and will simply take time to further report the results.

Monday night was supposed to be Iowans’ chance to vote for their preferred presidential candidate in the state’s caucus and give us our first indication of who will ultimately win the Democratic Party nomination. It would also be our first look at how states are upping their presidential election cybersecurity game since 2016, when Russia attempted to hack US voting machines — and which it is likely to attempt again this election cycle, and with four more years of experience.

With cybersecurity fears mounting, Iowa’s Democratic Party instituted a revolutionary new tool that no computer hacker can possibly defeat: a 2,200-year-old technology called “paper” as a backup to the new smartphone app that was designed to help tally votes. A few hours before the caucuses began, Bloomberg reported that some precinct chairs were having trouble downloading the app and logging in. That meant they’d have to call in the results instead, possibly delaying the results by several hours. Late on Monday night, some precinct managers reported waiting on hold for more than an hour while trying to report results.

The notion of some sort of technical failure in the 2020 election is not without precedent. In the wake of the problematic punch-card ballots that might have decided the outcome of the 2000 presidential election, electronic voting machines were seen as a way to improve accuracy and make elections more accessible. But after years of issues with the machines and fears that they could be hacked — culminating in the 2016 presidential election — many states dialed back their march toward a paperless future, returning to paper voting machines and paper backups.

The Iowa caucus doesn’t rely on voting machines at all; rather, caucus-goers meet at various precincts across the state and (in the case of Democratic caucuses, that is; Republicans have a different system), literally, vote with their feet. They stand in different sections of the room depending on who their presidential nominee of choice is. It’s not the most scientific process, but, as the first presidential nominating contest in the country, the result gives the winning candidate momentum heading into presidential primary season. The Iowa caucuses have predicted the correct Democratic nominee in seven out of 10 contested caucuses since it began in 1972. It hasn’t gotten it wrong since 1992.

The Iowa Democratic Party and the Democratic National Committee have instituted a few new measures this cycle that they say will increase security following allegations that Russia hacked the 2016 election. But some experts believe even these measures are not enough to ward off a determined and skilled hacker.

One of the chief concerns is the app that Iowa’s caucus volunteers are supposed to be using to calculate and register their precincts’ votes, which will be installed on their personal smartphones. As we’ve seen, smartphones can get hacked even in the best of circumstances. If one of the richest men in the world can have his cellphone hacked, how secure is a caucus volunteer’s smartphone?

Linn County Auditor Joel Miller told the Des Moines Register that he’s hopeful about the app’s security, pointing out that people routinely use smartphones for important transactions.

“We use smartphone apps for banking every day,” he said. “Hopefully this is as robust and secure as the banking applications.”

That’s not particularly reassuring, as even the most robust banking software is easily defeated if the user has poor cyber hygiene.

Party leaders have been sparing with details about the app’s security measures, refusing even to reveal which company designed it (they say this in and of itself is a security measure). The New York Times reported that the app has been tested by security experts and the Homeland Security Department. In 2016 — a simpler, more innocent time — both parties used a vote-counting app that was designed by Microsoft. Volunteers who do not wish to use the app or don’t have a smartphone can always call in the results through a hotline.

And, as an added measure of security and for the first time in caucus history, the Iowa Democratic Party is instituting a “paper trail,” giving caucus-goers a card on which they must write their preferred candidate’s name and their signature, to be collected by the caucus precinct. These will be used in the event of a recount. Laws requiring some kind of paper record for votes vary state to state, with only 13 not requiring them at all. Iowa, for the record, is one of 14 states that require paper ballots (this is a caucus, not an election, so the law does not apply in this case).

Russia’s most effective tool in influencing the 2016 elections was not hacking voting machines but a widespread disinformation campaign that largely played out on social media. It will almost certainly continue this strategy in 2020. Social media platforms say they are attuned to the threat and have instituted various measures they believe will prevent the anticipated misinformation onslaught. Their ability to identify and remove hoaxes from their platforms, however, remains spotty.

The Iowa caucuses are a quirky process but a symbolically important one, both for who wins them and for their ability to resist interference attempts from bad actors. A smartphone app hack wouldn’t be the end of the world — thanks to the new paper trail, it should be easy enough to get the correct tally anyway. The biggest damage would probably be the ominous tone it will set for the rest of election season, casting that much more doubt on the eventual vote.

Author: Sara Morrison

Read More