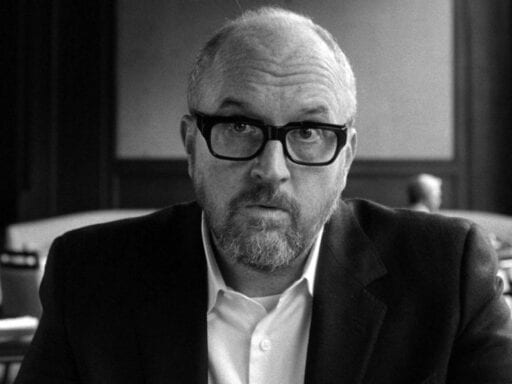

Louis C.K.’s return speaks to deep misogyny in the comedy world.

As I sat in the police station shaking with anxiety and anger as I prepared to report my rape, a thought entered my head: I am lucky.

The reason? I’m a comedian and satire writer, and my rapist — also a comic — wasn’t famous and successful. In the male-driven comedy world where status drives everything, I consider myself lucky. I was able to speak out about my assault without legions of people from the comedy community defensively protecting their own.

The women comics who came forward about Louis C.K. non-consensually masturbating in front of them? They’re less lucky. Their harasser was a world-famous, critically renowned comedian. Mine was a nobody.

In August and September, C.K. made two unannounced appearances at the Comedy Cellar, one of the biggest and most revered comedy clubs in New York. In both instances, he worked out new material like nothing had changed. The club owner was happy, the audience was happy, except for the women, and several people walked out. It was as though his crimes had never happened.

Whenever some stranger on social media asks how long C.K. should be punished, and how long we should be bereft of his cutting-edge material about parades, women in comedy think, “What about us?” The conversation about Louis C.K. is always dominated by Louis C.K., even as we’re discussing what he could do to atone for the people he’s hurt.

What about the many women who quit comedy, or were and are forced out, because of sexual predators? Who is mourning their careers? I have seen so many women quit within the first year of trying standup — not because they didn’t have potential, but because they were pushed out by harassers, predators, and a general culture of toxic male dominance.

So many women have experienced misogyny in the comedy world

When I put out a call on Facebook and Twitter a few months ago for stories of women who’ve felt like they were being pushed out of a comedy space by male comics, my inbox was flooded. I heard from women who felt forced out of sketch and improv troupes because their harassment was treated like part of the joke. I heard from women who moved because their rapists made them keep losing bookings and jobs in their city — either by spreading rumors or by contacting bookers directly (It’s a common joke in the community that NYC, LA, and Chicago have a comedy rapist and rape victim exchange program). I heard from women who lost even their closest friends in the comedy world because they spoke out.

It’s hard to say why misogyny is so prevalent in the comedy community. It might be because performing comedy is such a vulnerable act, and our society hates to see women be vulnerable. Or maybe it’s because comedy is such a difficult career choice that we’ve created some sort of cult of “toughing it out” even if the “it” is assault.

So when male predators like Louis C.K. or T.J. Miller are allowed to so cleanly return to comedy (and no, alleged abuser Chris Hardwick doesn’t count; I refuse to call him a comic), it sends women a message about our workplace. It tells us, again, that women are unwelcome and unsafe.

A path to redemption starts with victims

When people ask me what C.K. is supposed to do with his comedy career following these allegations, I tell them that if this were just about his career, I’d be happy to let him try and come back with his groundbreaking jokes about rape whistles. But it’s not. It’s about the careers and safety of women in the comedy world. It’s about the women whom C.K. and his manager Dave Becky, by his own admission, verbally threatened as part of the cost of being assaulted.

Sure, there can be a path to redemption for these men. I think that path would look something like what comedian Jenny Yang laid out on Twitter: private apologies, calling on gatekeepers to support the women who were hurt, supporting survivor networks and charities, etc.

So you’ve admitted to sexually assaulting comedians in a work culture where fellow people of power took actions to keep the victims not working and quiet about the offenses so that you could make millions and keep working. HOW DO YOU ATONE FOR YOUR SINS? A THREAD OF SOLUTIONS.

— Jenny Yang (@jennyyangtv) August 28, 2018

If C.K. wanted real redemption, he would have asked the women he hurt how he could make things right. He would have focused on understanding them, not just being understood himself.

A predator’s seamless return reflects a fear we have every day: that we are not welcome.

I can’t speak to everyone’s experience, but I know that I’ve had to consider the long-term impact on my career if I rebuff a male comic’s advances. Every time I’m offered a spot with a guy I’ve heard rumors about, I have to think twice and consider my own safety.

But hey, I — and so many other women comics whose harassment stories filled my inbox —am still here. And we can’t be pushed out by your dick, your paycheck, or anything you say into a mic (which is probably about your dick).

Of course, the conversation about Louis C.K. and whether or not he should return inevitably comes down to his talent and his status, as it does for so many of the abusive men the comedy world doesn’t want us to leave behind. It’s going to involve a conversation that weighs the careers of those who have had the privilege to move forward and the privilege to prove themselves over those who did not. To which I say: God, I’m so glad my rapist wasn’t funny.

Man, I’m so lucky he sucked at comedy.

Hana Michels is a comedian and writer in Los Angeles. She currently writes and edits for Bunny Ears. She went viral for dating guys who own swords and for doing toilet paper wrong.

First Person is Vox’s home for compelling, provocative narrative essays. Do you have a story to share? Read our submission guidelines, and pitch us at [email protected].

Author: Hana Michels